Introduction

MY SRI LANKAN STORY BEGINS WITH ME STANDING ON THE VERY TIP OF SOUTHERN INDIA, STUNNED, BECAUSE DAD WAS ABOUT TO TRY AND JUMP OUR PRECIOUS AUSTIN MINIBUS (CONTAINING EVERYTHING WE OWNED) OFF A RICKETY WHARF ONTO TWO LINKED DUGOUT CANOES. THIS STRANGE BARGE WAS TO BE PADDLED OUT TO A FERRY AND OUR MINIBUS HOISTED LIKE A COW ONTO THE SRI LANKA-BOUND VESSEL. I WAS FOUR-AND-A-HALF YEARS OLD.

We had already driven the minibus from the UK across France, Germany, Austria, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Turkey, Iran, Pakistan and India. Our arrival in Sri Lanka would mark the return of the prodigal son, Wickramapala Kuruvitamy fatherwho had left home on his Indian motorcycle many years earlier to seek his fortune in England.

It must have been quite a sight: five-and-a-half of us packed into an Austin minibusDad, my Austrian mother, Liselotte Katharina, me, my eight-year-old brother Philip and, at the last minute, a Sri Lankan cousin who wanted to come along for the ride. The half was my unborn brother, David SangeevaMum was four months pregnant when we set out from the UK.

Our familys journey began in London in February 1968 and was due to be completed seven weeks later. Dad, the head of the London house of Kuruvita, had nursed the concept of this daring expedition for a long time. Now, after closing his business in London, his plan was to take the family overland to his hometown of Dehiwala, just outside the boundaries of Colombo. We all trusted in Dads ability to pull us through any difficulties, and so his dream became reality.

The excitement of preparation was great. Dad charmed Lord Primrose (who was thirteenth in line to the British throne but preferred to do his own thing in a workshop close to Dads) into selling him the almost new Austin minibus for 20 pounds.

But because Mum was pregnant, Dad was worried about her undertaking the trip; he suggested she take a plane instead of risking her own and the babys life in the middle of some wilderness. This was completely unacceptable to Mumhow could she possibly forgo such an adventure? In the end Dad agreed, but found an insurance policy that would fly her home should she need evacuation; he craftily worded the document in such a way that home could mean London or Colombo.

The British Automobile Association provided detailed information on road conditions, distances, sights of particular interest and places where we could buy petrol en route. Eleven countries, three ferries and roughly 20,000 kilometres would be involved if we were to accomplish this journey. We had to drive through snow and ice, over mountains and deserts, and finally through the unforgiving heat of the dry season in India. Forty-one degrees Celsius in the shade made Dad decide to drive day and night to get to our destination one week earlier than planned.

After a visit to the 400-year-old temple at Madurai in southern India we were informed that Danushkodi could only be reached by train; and the minibus had to be loaded too. From Danushkodi, a ferry would take us across to Sri Lanka.

Danushkodi was a desolate, sandy outpost with only a large cadjan shed, thatched with coconut leaves, housing the immigration and customs officers. There were long queues stretching out over the white sand. The seafront was cordoned off and the ferry was only just visible more than a kilometre out from the shore. Dad stood all morning in the burning sun trying to clear our passage, only to be told that it was impossible to take the minibus to the ferry: the last cyclone had washed away the pier. The next available port was Bombay, about 1400 kilometres away.

The best time for Dads particular genius to spring forth was when a situation became desperate. He asked us to stay put, and disappeared. Not long after, he returned with the owners of two dugout fishing canoes, showed them how to tie their flimsy craft together, and paid for some of the ferrys cargo nets to be spread out on special wooden blocks on top of the newly created barge. By that time a huge crowd had secured a premier place on the beach to see what spectacle would unfold. My mother gaspedshe realised what he intended to do and was frightened. Only that morning we had experienced the quicksand on the shores when we drove closer to the water to cool off. Some kind villagers had come to the rescue and helped to dig out the wheels. What would happen this time?

We children were quiet, and everyone held their breath as Dad lined up our vehicle, accelerated to skim over the top of the treacherous sandy surface and landed with screeching brakes precisely on the two little canoes. He had to wait three hours for the tides to be right before a tugboat was able to pull him and his eccentric rig across a stretch of sea to meet the ferry.

Meanwhile, one small group at a time, all the other passengers boarded an old, wobbly sailing boat hauled by a tug, which took them out to the ferry. By the time Dads strange procession came alongside, we were all standing on the ferrys upper deck watching. The ships crane reached out and secured the minibus, ready to hoist it onto the cargo deck. Precariously balanced, it suddenly slipped, dangling halfway between the sea and the safety of the deck. I had asked to be picked up so I could see better, but when it looked as if the minibus was about to fall back into the sea I became hysterical, shouting Daddy, Daddy, my Daddy! I thought Dad was still in the minibus. With typical Wickramapala aplomb he appeared behind us, the minibus was successfully stowed on board and the ferry was able to set off.

We finally arrived in Sri Lanka exhausted but safe.

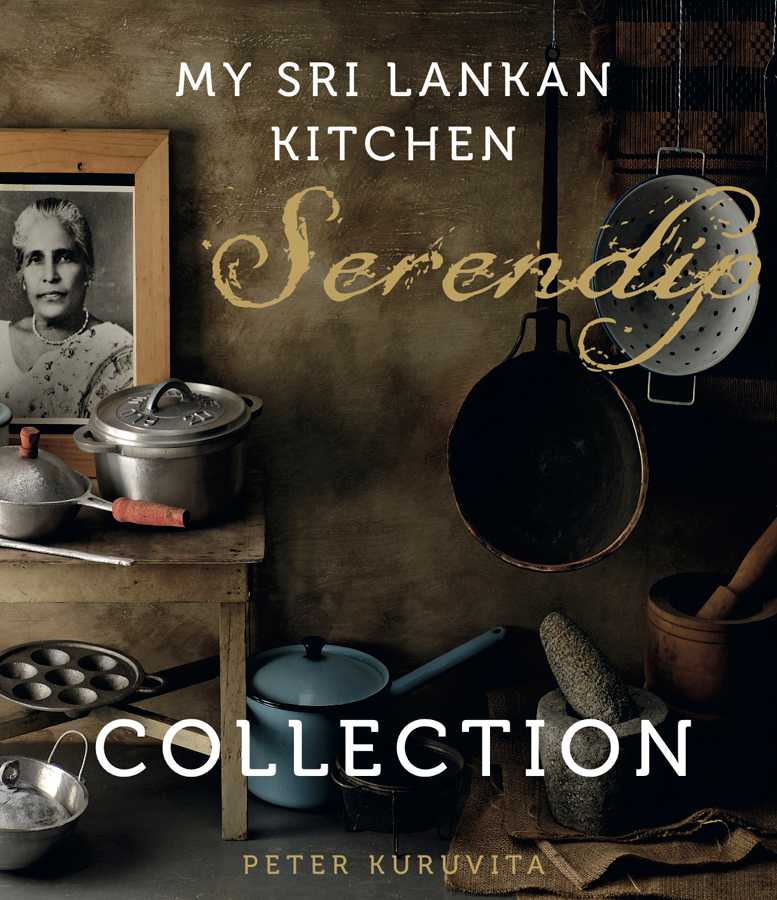

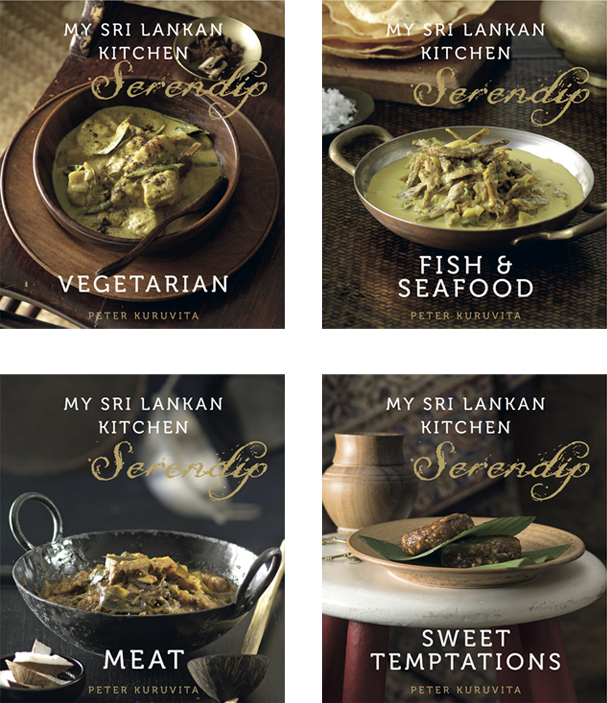

Serendip - Meat

MY ACHIS KITCHEN WAS THE CENTRE OF OUR FAMILYS UNIVERSE. IN IT, THERE WERE LOVE MATCHES, FIGHTS, DRUNKEN UNCLES, WEDDINGS, SPECIAL FULL MOON RITUALS, WONDERFUL FOOD AND THE TRAVELLING CHEFS WHO WOULD ARRIVE IN BULLOCK CARTS WITH THEIR MASSIVE POTS AND COOK FOR HUNDREDS. I FEEL VERY LUCKY TO HAVE BEEN GIVEN SOME OF THE RECIPES THAT WERE NURTURED THERE.

MEAT CURRIES

The main meat market near our compound was at the end of Hill Street in Dehiwala Junction. It was a seven-day-a-week operation and was run by the Muslim community. I was always the first to put my hand up when someone was goingit was so exciting and colourful. (The market is still there, with the sons of the original butchers now running the show.)

Getting dressed up was a mustit is wonderful to live in a country where people, no matter how poor they are, will always ensure they are well turned out before leaving the house. I had to put pomade in my hair and comb it, ensure I had on a collared shirt and long trousers, and put something on my feet. Formal shoes were optional but some kind of footwear was essential.

Once ready, smelling and looking like a peach, I would head out with my aunties, all of them wearing saris, and walk down to the Junction.