But remember, this was also known as the Garden of Eden. It panders to anyones chauvinism, you know: Sinhala, Tamil, aboriginal. Choose a religion, pick your fantasy. History is flexible.

Romesh Gunasekera, Reef

Eating the food of any country can be a simple delight. However, if you delve deeper into the place and the people, things become a bit more interesting, and you can gain a deeper understanding of that food. Sri Lankas history is fascinating, tangled and full of legends. We can only take a little look at it here, but I would encourage you to dig deeper and discover more (perhaps start with the ).

First up, the name or names. Lanka is Sanskrit for island, and in Tamil it means glittering. Arabs and Persians called the island Serendib or Serendip, linking it to the word serendipity. The Ancient Greeks called it Taprobane and the Portuguese knew it as Ceilao, which led to the British, Ceylon. It is now officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, or Sri Lanka for short sri meaning resplendent.

So here we have a glittering, serendipitous, resplendent island.

Sri Lanka was first inhabited by the Vedda, the countrys indigenous people. They are traditionally hunter gatherers, with a diet rich in meat and seafood, wild honey and traditions of preserving. Like many indigenous cultures they believe in animism, the idea that everything possesses a spiritual essence. Their culture has been slowly disappearing for a long time now, swallowed by assimilation and the modern world. Despite this, there are some remaining peoples interspersed in Sinhala villages in the south-central jungles of the island and there is one village, in Maduru Oya National Park, named a Vedda reservation site, where there is a tribe still adhering to traditional ways.

From as early as the third century, there was a lot of movement between India and Sri Lanka. The close proximity of the two countries (an almost walkable distance) meant there was always trade, migration and the occasional invasion.

In the fifth century, a disgraced prince from northern India was banished to the island, along with hundreds of his followers. Prince Vijaya converted to Buddhism, established a kingdom and became the first traditional king of Sri Lanka. While the many versions of this particular tale are classified as legends, it seems to be generally accepted as the origin of the first Sinhalese people.

In among these two distinct peoples was the constant trickle of Hindu Tamils from south India, but it wasnt until the 1200s that they began establishing their own kingdoms, while keeping strong ties to southern Indian culture and food. At this stage, the Sinhalese kings were making themselves comfortable ruling in the south, with the Tamil Sri Lankans ruling a kingdom in the north and in Kandy, in the interior.

Although trade routes were established as early as the first century, it wasnt until the seventh century that the spice trade became firmly established. Due to its position in the Indian Ocean, and the fact that the country was bountiful in spices, jewels and ivory, Sri Lanka became very important. It attracted Arab traders, who are still a part of the population today and with them came a whole strand of food traditions. There were also Malay and Chinese merchants to-ing and fro-ing, and Sri Lanka, as a great port city, welcomed them all, adding them to the melting pot of cultures and foods.

The Portuguese arrived on the scene in the early 1500s and decided they wanted to be in charge. After a lot of trouble and violence, they eventually got their way and ruled most of the island for a good century and a half. The Portuguese brought firepower, chillies, semolina, tomatoes, breads and Christianity. They married locals, made fish patties and left behind surnames like Fernando, De Silva and Pereira.

After that it was the Dutch. They wanted power through trade (it was the time of the formation of the Dutch East India Company), and at first it seemed they wanted to make friends. But this quickly turned sour, and the Dutch ousted the Portuguese in the mid 1600s with the help of the Sri Lankans who thought they were going to be done with foreign rule.

Alas, the Dutch stayed on. They never quite conquered the whole of the island, but they did create a lot of commerce, planting coffee and tobacco and selling ivory, cinnamon and jewels. This was the beginning of the Burgher people (again the result of some intermarrying) and what was to become another distinct strain of food: richer, using ghee and more meat (Dutch Christianity allowing for any animal to be fair game).

Then came the British, in the early 1800s, and Sri Lanka was swallowed into the Great Empire. For Sri Lanka, this marked the end of its monarchy and kingdoms; for Britain, it was all part of their grand colonial hopes to civilise the natives of the world. The British legacy is noticeable in the islands architecture, education, rail network and proliferation of English speakers.

The British put a lot of energy into the coffee trade before a coffee blight hit, then they moved to tea. This became quite prosperous, but unfortunately on the backs of Tamils forced to migrate and work under appalling conditions this population became known as up-country Tamils as a way to distinguish them from the earlier Tamil migrations.

At the time, Sri Lanka was a trilingual society Sinhala, Tamil and English the official language being English, with the British favouring the English speakers of the island. This was an issue for the majority Sinhalese population because it meant favouring some minorities: the educated and predominately Hindu Tamils and the Burghers.

In 1948 the country gained independence. The British departed, leaving behind the name Ceylon and a power vacuum, where language became a point of contention. This led to what is now known as the Sinhala Only Bill, passed in 1956, declaring Sinhala as the official language of Sri Lanka. This shift changed the power balance and would come to have great repercussions. It was a period marked by a push for nationalism aimed at appealing to the Sinhalese majority.

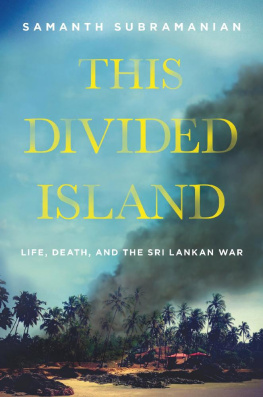

Riots began in the late 1950s and led to the further erosion of Tamil rights; Ceylon became the Republic of Sri Lanka in 1972 and security forces imposed numerous discretionary laws against the Tamils. Mounting tensions exploded into a violent civil war between the Sri Lankan army and the Liberation Tamil Tigers of Elan (LTTE), who formed in 1975 and fought for the right to have their own land, Tamil Elan in the north. Officially starting in 1983, this was to become Asias longest-running insurgency: 28 years of extreme violence from both ends. Finally, in 2009, the war came to a bloody end with the death of the leader of the LTTE, Velupillai Prabhakaran.

I happened to be there in January the following year, when the first post-war election was held. The mood was apprehensive and rumours of corruption were rife, with tussles breaking out between people of opposing parties and stories of election scams.

Since then, the country has been re-building and coming to terms with the years of devastation. Tourism has picked up, as has trade. Foreign investment is gaining a foothold, for better or worse. Expressways are appearing and buildings are being restored. Even though you still need a special permit, travelling north to Jaffna is allowed. Progress has been slow, hampered by the 2014 tsunami, and along the coast and up towards the north, the scars of this and the war are still visible.

Next page