For a book three years in the making, the list of persons to thank and acknowledge would obviously exceed the limitations of space allotted here. So we will restrain ourselves! First and foremost, our thanks to our editors and publisher who very kindly and patiently put up with us as we waited for the soft morning light to touch the weather-beaten surface on that particular day of the year in the second monsoon with wind blowing from the northeast.

Equally we wish to thank all the owners of the properties, whose unfailing patience and graciousness in letting us invade their privacy makes the book what it is. Since many of them specifically asked not to be mentioned, we remain silent on all their identities. Some we cannot go without mentioning, even if they want us not to. Anjalendran for his unfailing criticism and encouragement. We think we still fall far short of his high standards, but it motivated us to be clear about how we approached this book. Professor David Robson for his patient reading of the first drafts and being an indulgent host. Kaushik Mukkerjee, Priyanka Samaraweera, P. G. Dinesha Dilrukshi and Shiromi Rajapakse, whose hard work and company made our lives easier. And mostly to our families and friends for putting up with never-ending descriptions of a book that lately even theyfirm believers in us seemed to doubt would ever come out.

The Serendipitous Isle

As the haze of twilight descends on Kandy (mountain), the citadel of the last kings of Sri Lanka, called by many Sinhalese people Mahanuwara or the great city, the oboes and rolling drums that mark the evening worship at the sacred Temple of the Tooth Relic reverberate throughout the valley. On the northern slope of this valley, in a place of worship planned and built by missionary teachers of an Anglican Christian school, the sound of evensong melds with that of the temple drums. This is a typical example of the fusion that is contemporary Sri Lankan style. The chapel for Trinity College is built of warm honey-colored granite that was brought in from a quarry 5 miles (8 km) away by elephants, and designed by the British Vice-Principal Gaster. Started in 1922, it simply copies and uses for a different purpose the most common of vernacular Sri Lankan buildingsthe open pavilion.

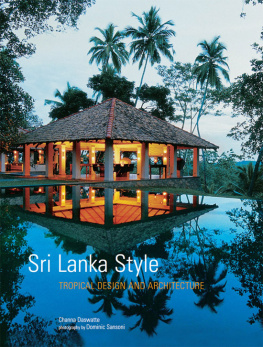

The pavilion is the quintessential Sri Lankan building. From the simple wayside shelter ( ambalama ) that dots the pilgrim routes, to the drumming halls of the pilgrimage centers, right up to the very center of government, the Magul Maduwa (Hall of Royal Audience), open-sided pavilions with huge overhanging roofs were the central spaces for life in Sri Lanka. The salubrious climate only required that a dwelling function as an umbrella, protecting its occupants from the sun and rain, while allowing air to enter.

These spaces contained nothing more or less than the objects that were essential for everyday life. Each object, however, was beautifully crafted to suit its purpose and the means of the occupant. A palpable sense of peace and discipline pervaded the atmosphere. This was a result of a complete control and discipline of making space and putting material together. The only bounded enclosed space in many of these traditional dwellings was perhaps to store things. Even today, most Sri Lankan village houses have no more than one enclosed space.

The village houses and dwellings of the populous were of the simplest possible construction and design: wattle-and-daub ( warichchi ) structures carefully covered over with mud and cow dung and roofed with plaited coconut fronds. Traditionally, only the building of the feudal lite and religious structures had lime-washed walls and clay shingle roofs. Thus, while these buildings stood out against the lush green landscape, along with the brilliant saffron robes of the monks, those of the majority of the people blended back into the landscape. Essentially a non-urban architecture, these vernacular structures were placed with great skill in relation to each other on the landscape. This is epitomized by the thirteenth-century temple and monastery of Lankatillake outside Kandy.

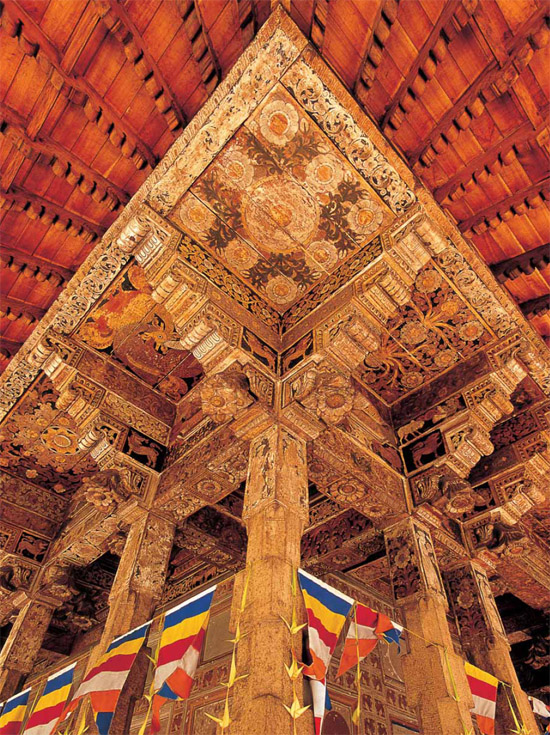

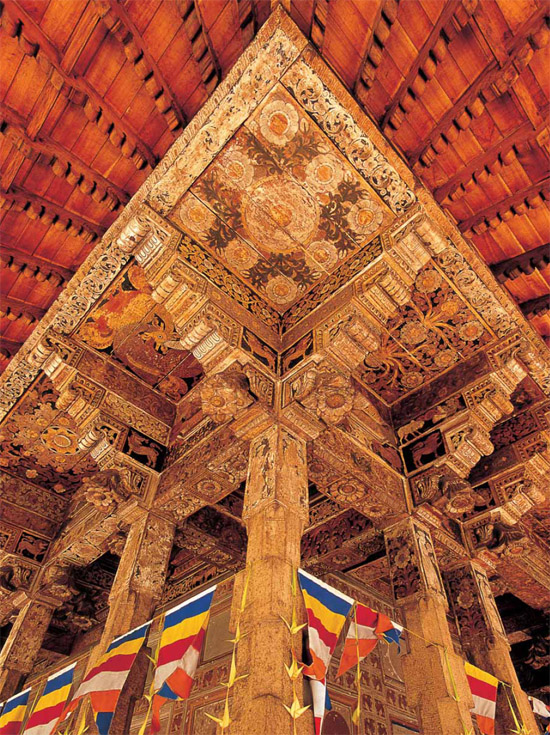

Whilst residential interiors of traditional houses were plain and contained only the beautifully crafted utensils and objects of everyday life, the interiors of religious and ritual buildings were in complete contrast. Dealing with the supra mundane, these interiors are a fantasy of color and pattern: here, polychrome walls and statues compete with brilliantly colored temple hanging cloths and curtains.

The accommodation of ritual functions in other buildings was accompanied by temporary decorations such as the Rali Palamas, literally bridges of waves, made from bright-colored calico, usually the traditional colors of red and white, and bamboo frames. Other temporary decorative structures accompany various ritual functions such as funerals, weddings and curative practices like the Sanni Yakkumas and Bali ceremonies that are performed to avert disease and other disasters. These are amplified by the brilliant colors of the costumes. The temporary decorations that accompany Christian religious feasts, such as arches of coconuts and flowers, sometimes remind one of northern Spain or Portugal, from whence Catholicism was introduced to the island in the sixteenth century. Others are adaptations of Eastern practices such as the decoration of a mast that represents a tree of flags, which derives from the Eastern practice of decorating sacred trees. Strings of mango leaves over a door with a pair of banana trees in fruit mark Hindu households on the religious holidays of those believers.

Intricately carved and painted pekada column capitals and ceiling support the even more highly embellished roof structure at the Temple of the Tooth in Kandy.

The colonial tradition, like in most other Asian situations, adopted local building methods and techniques. These resulted in sensible buildings that addressed the issue of living in a tropical environment. The colonials also introduced principles of classical order to the construction of houses. Both in planning and detail, classical principles began to be absorbed by Sri Lankan builders. By the end of the eighteenth century, Sri Lankan architecture was a unique blend of local construction tradition and Western classical planning principles. This pervaded the whole gamut of architecture, from the smallest wayside shop to the most extravagant mansions of the local ruling class, the Ratemahatayas and Mudliyars.

Although the monsoon climate of the Indian subcontinent seemed both beneficial and beautiful, the heat and humidity, aided by termites and fungus, destroyed even the most solid of materials. This spurred craftsmen to employ easily renewable material on decorations. One of the simplest materials available for finishing a house on this coral reef-rimmed island was lime wash or hunu . Occasional color came from the use of a mud-based samara or yellow ochre paint. Doors were painted with a variety of vegetable dyes stabilized with dummala resin.

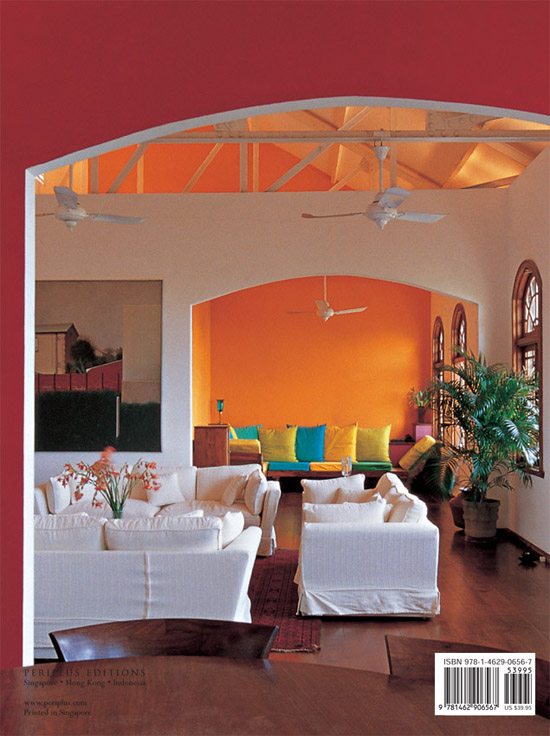

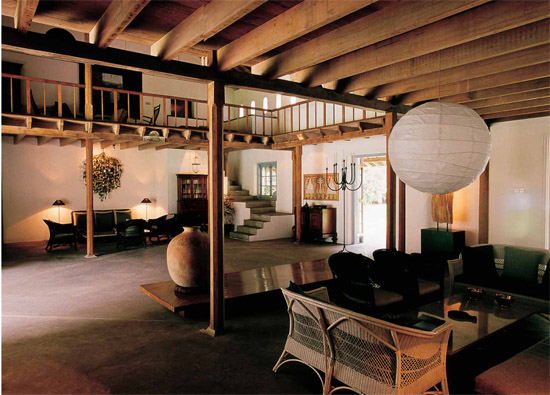

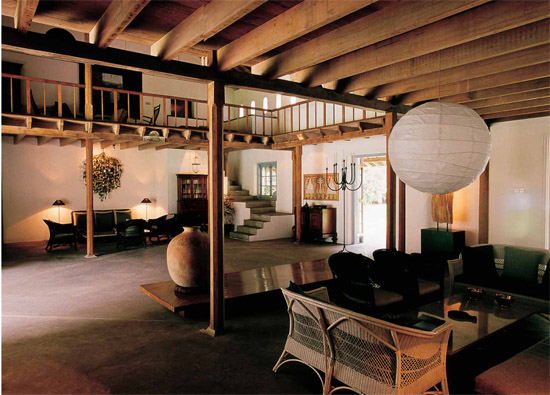

The cool interior of the former horse stalls at the old manor house of Horagalla (page 42) has been converted into the main sitting room, with four main areas for sitting, two up and two down. At one end of the room, a small cement-finished staircase leads to the upper levels which are connected by a bridge-like part of the original hayloft.