The New

Bali Style

A Fresh Approach

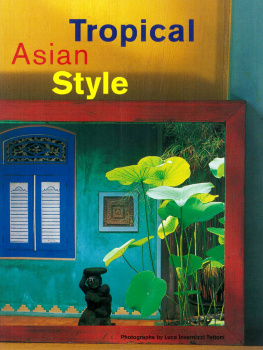

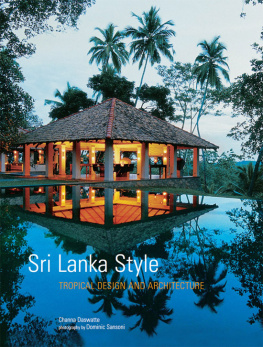

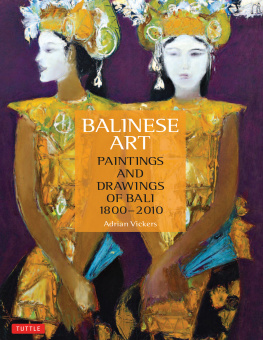

The "Bali style" of architecture and interior design is renowned and increasingly popular the world over. How it came into being is a story of cross-cultural legacy and an amalgamation of different design elements. In this chapter, we explain the connection between religion and architecture in traditional Balinese design, trace the development of new styles in both commercial and residential buildings and see how a thoroughly modern, international architectural form has been born.

Bali - one of the smaller of the islands that comprise the Indonesian archipelago - has long been a magnet for foreigners. Just eight degrees south of the equator, it offers a landscape of great contrasts: beautifully modulated rice terraces, majestic mountains, fiery volcanoes, serene lakes, coastal lowlands and limestone fringes. This landscape -along with the unique culture of its inhabitants -has attracted artists, travellers, anthropologists, or simply the curious, who have flocked to the fabled isle in ever-increasing numbers.

In their desire to settle and forge a new life, many have sought to replicate the comforts of home but reinterpret these in a "Balinese" way. They have built - or had built - tropical dream homes that take elements from their own heritages and combine these with Asian influences and styles. The result has been a plethora of residences in many different designs, but all loosely gathered under the umbrella term of "Bali-style". To accompany the architecture has come the interior design: a type of indoor-outdoor living style that has its roots in the climate of the tropics, but its application in Western traditions of comfortable furniture and furnishings.

To understand how this has happened, one needs to look back in history. Separated from its neighbour Java only by a narrow strait less than two miles across, many of Balis people are descended from the last of the Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms in Java, the Majapahit dynasty Others stem from what is known as the Bali Aga, an older stratum of society with animist beliefs. The merging of the two resulted in the present Balinese Hindu religion and the so-called post-Majapahit Balinese style of architecture. This is described by Julian Davison in Balinese Architecture (Periplus Editions, 1999) as "grounded in a metaphysics that presents the universe as an integrated whole... where microcosm is perceived as a reflection of the macrocosm. Correct orientation in space, combined with ideas of ritual purity and pollution, are key concepts providing a cosmological framework for maintaining a harmony between the man and the universe. This view derives from the Hindu idea of a divine cosmic order (dharma) , qualified by a much older animistic tradition which attributes spirituality to the natural world."

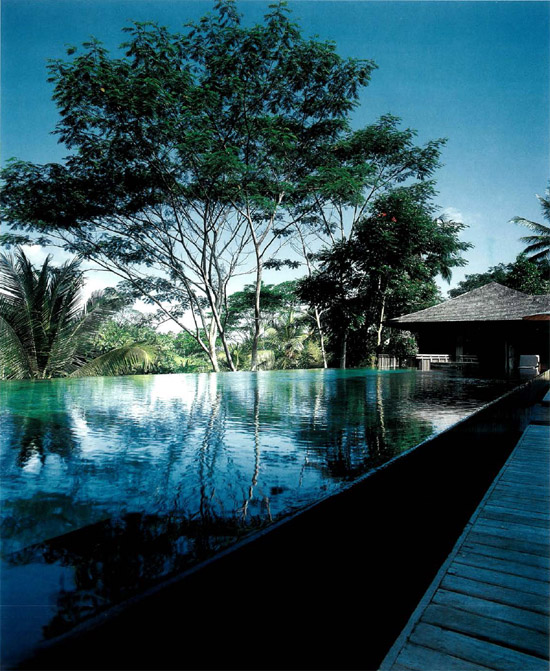

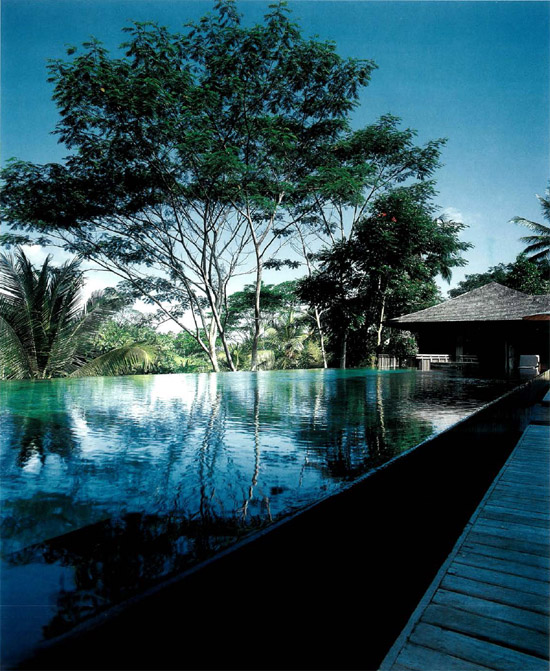

A Plumeria tree shadows this emerald green pool designed by the architect Gianni Francione; it sits comfortably in the tropical environment and enjoys an uninterrupted view of rice fields around.

The pure rectangular volume of this infinity-edge pool protrudes above the wooden deck. This very refined composition was designed by the architect Cheong Yew Kuan, for the villa Tirta Eningat Begawan Giri Estate.

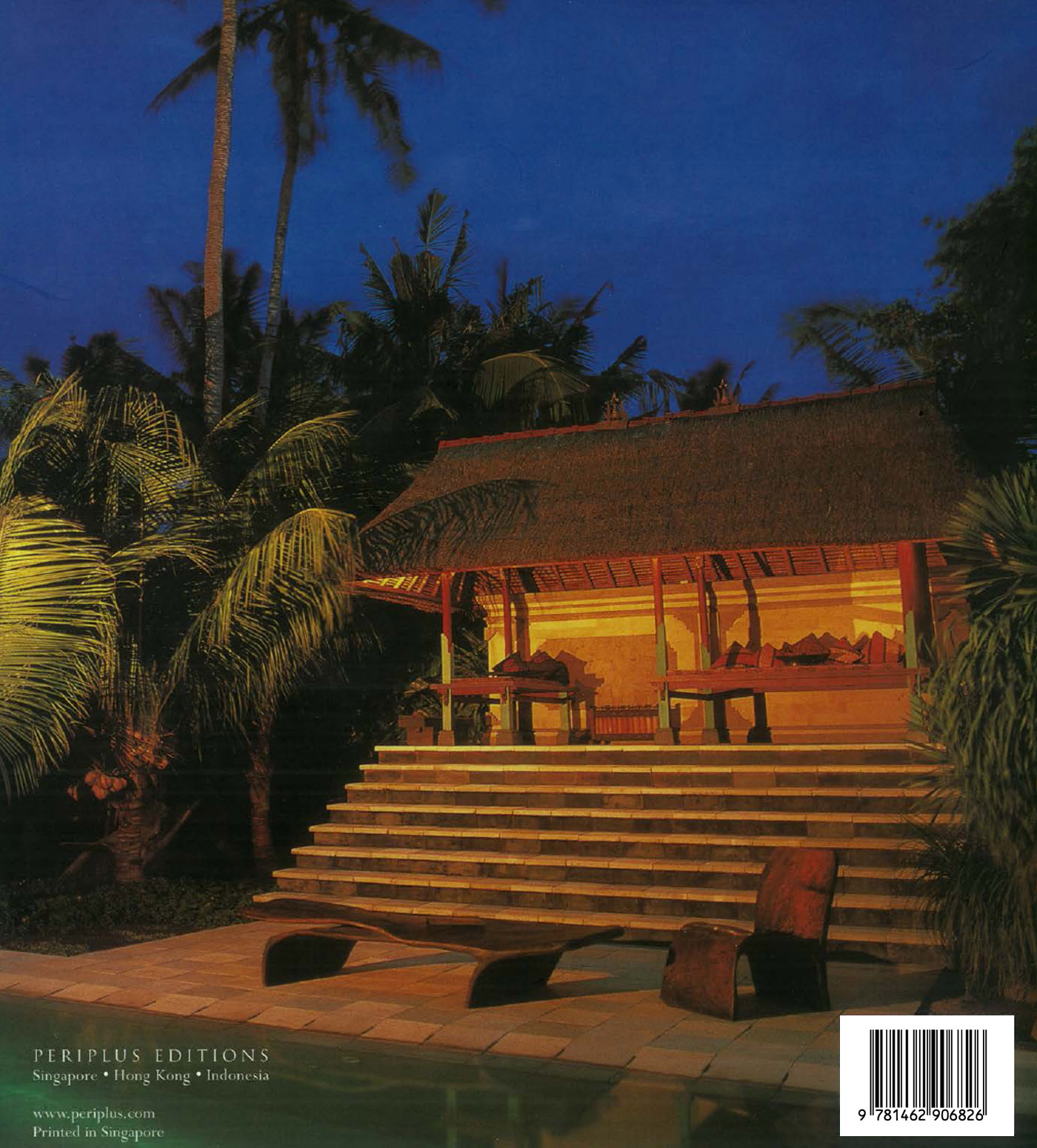

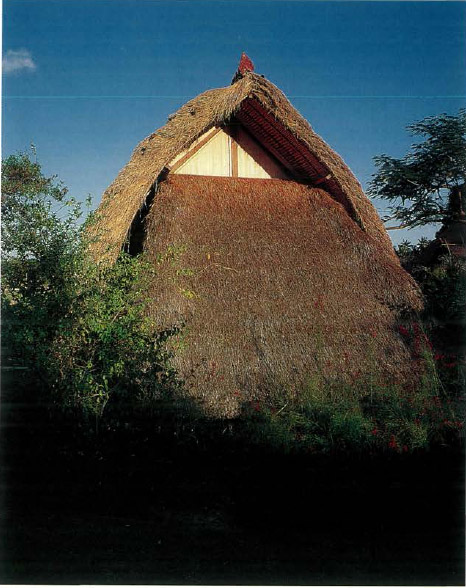

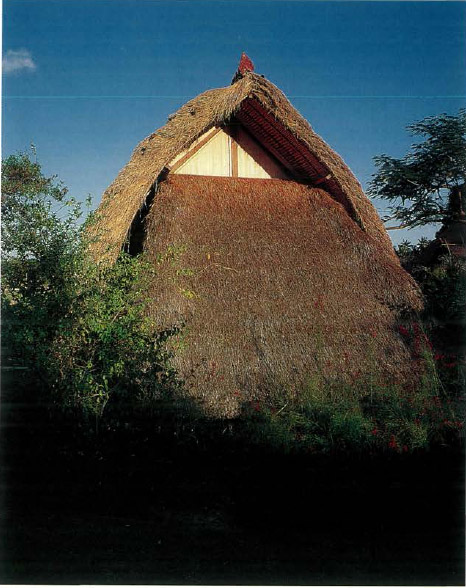

The characteristic shape of the roof of the Balinese lumbung or rice granary -here reinterpreted in a modern compound - has its own aesthetic appeal.

The tripartite organization of the Hindu cosmos and micro-cosmos and proper spatial orientation dictate the layout of all buildings in Bali: the Gods are on high, bad spirits are in the lowest regions and mankind comes somewhere in between. Before any structure is built, the undagi or local "architect" and expert in rituals, consults the ancient and sacred building manual "Asta Kosala Kosali". Here, every aspect of construction and design following strict rules of orientation, position, shape and size is predetermined. His job is to act as an interpreter of these sacred texts to produce a building that is in harmony with the human body which in turn will be in harmony with the Balinese Hindu cosmos. It can be seen, therefore, that architecture, as such, is not a secular art with aesthetic or functional or decorative intent, but rather a religious ritual. It is adat, a vital thing, not an art form in itself.

Many outsiders misrepresent this idea of Balinese architecture. When they use some thatched material for the roof, or incorporate a small carved door or hori as a gate, or install a partition wall or aling aling at the entrance, they are not participating in an evolution of Balinese architectural style. Rather, they are taking these traditional elements, putting them in a modern context and reinterpreting them in a decorative and aesthetic way. This "dipping into" the Balinese cultural box started when the first foreigners settled in Bali; it has evolved through the years and has left behind a rich architectural legacy.

Many of Bali's first settlers, the most famous being the painter Walter Spies, built houses that were Western interpretations of traditional Balinese constructs. Spies' house, built in Campuan on the outskirts of Ubud in the 1920s, may still be viewed today. A simple, two-storey structure in pavilion style, it utilized Balinese materials and craftsmen, and was decorated with local paintings and carvings. It is the precursor of many similar houses that were built by Westerners who followed in his footsteps.

The late 1960s and the early 1970s saw the advent of western tourism on a scale unprecedented before. The first response to this was the construction in 1963 of the 8-storey Hotel Bali Beach in Sanur, a Japanese government reparation gift to Bali. The building, an example of Tokyo international style, dominated the skyline and caused major damage to the local environment. Luckily for Bali, it was a one-off rather than the beginning of an indiscriminate concrete building boom. On a more tasteful level, these were also the years of the Oberoi Hotel designed by the architect Peter Muller, and Kerry Hills Bali Hyatt in Sanur. Both works were the first interesting responses to the problem of how tropical architecture could and should be adapted for the tourist industry in Bali.

The Ibah hotel in Ubud employs extensive use of alang-alang thatchlng in its roofing. Perched on the edge of a gorge in Campuan, it is modern in concept, but traditional in its use of materials.

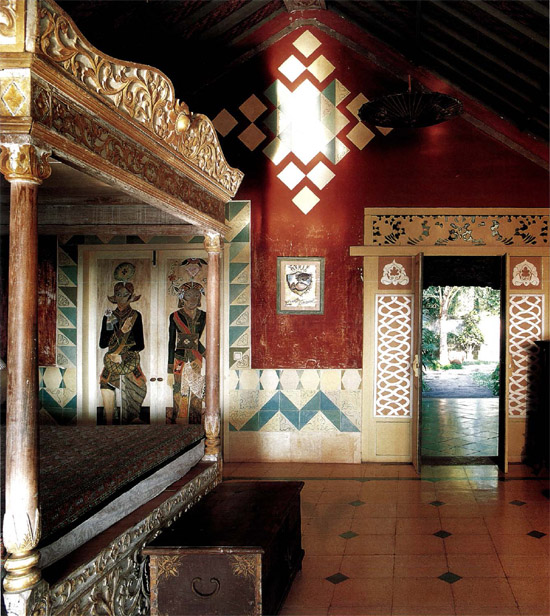

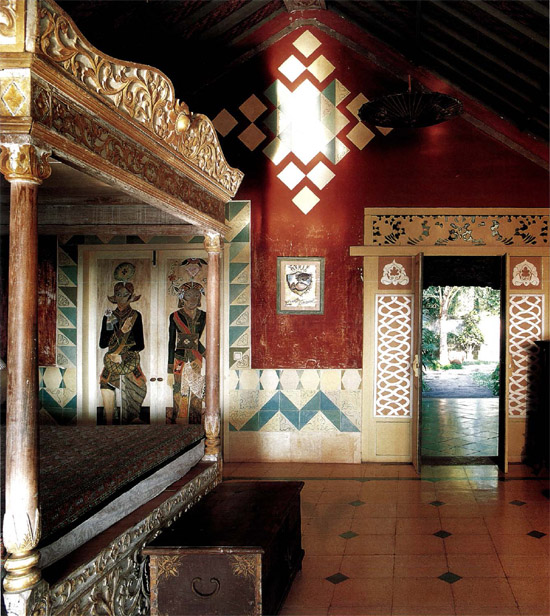

The walls of The Royal Suite at Taman Bebek hotel, Sayan, as realized by Stephen Little, feature geometric patterning and a modernistic paint finish.

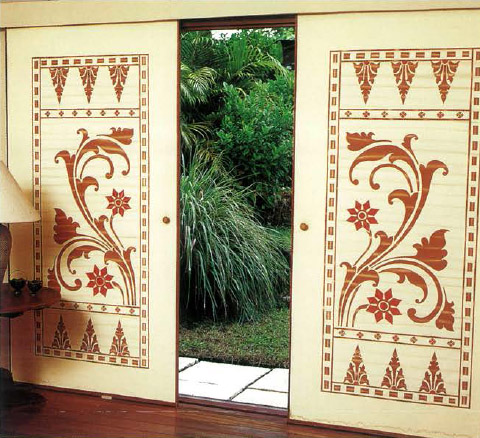

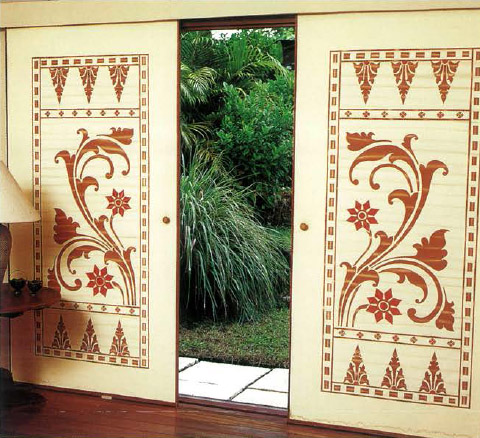

The elegance of this traditional floral motif is highlighted in these hand-painted panels by the artist Pierre Poretti.