CHAPTER ONE

Sacred Ceremonial Cuisine: Food of the Gods

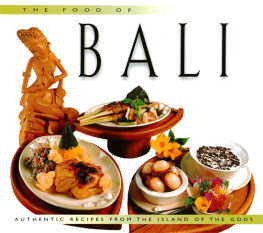

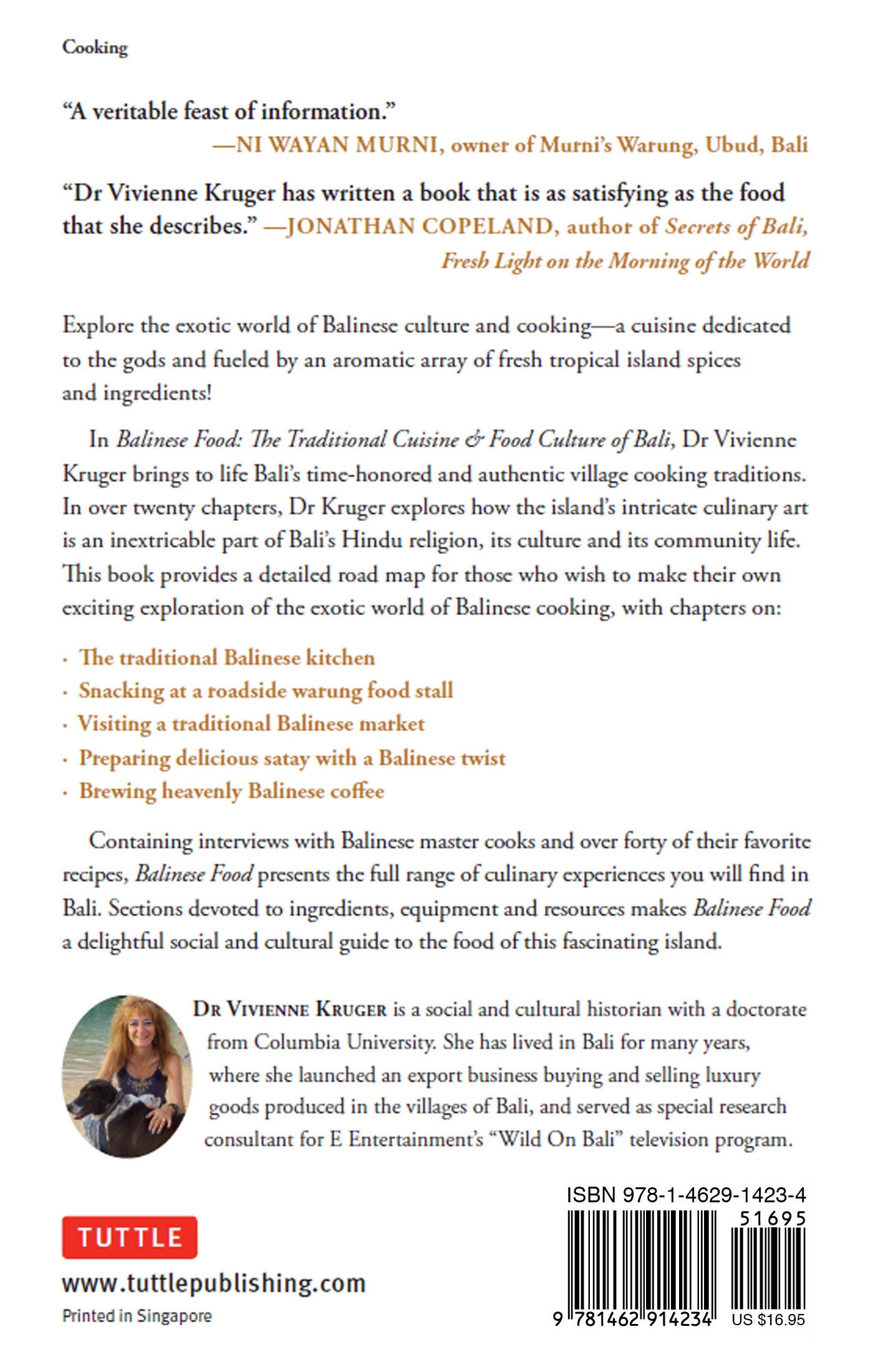

B ali, the green jewel in the fiery heart of the Indonesian archipelago, is graced with fertile rice fields, rich volcanic soil, flourishing fruit trees, edible wild greens, plentiful fish and a natural supply of fragrant herbs and spices. Born and bred in equatorial abundance, Balinese food has evolved into a cuisine full of exotic ingredients, aromas, flavors and textures. It also plays a pivotal role in Balinese religion, ritual and society. The Balinese cook in order to eat as well as to honor, please and serve their gods. They incorporate their traditional values into their food. To understand Balis cuisine, one must appreciate the tripartite role of food as vital human sustenance, sacrificial offering to both respect the gods and appease the demons, and essential ritual component of Bali-Hindu religious ceremonies. As with everything else on Bali, food is inextricably intertwined with faith. Behind high family compound walls and on bale banjar (neighborhood meeting halls), entire communities make ceremonial quantities of colored rice, sweet rice cakes, meat-filled banana leaf offerings and regulation rows of skewered chicken satay offerings for the gods, who will absorb the sari or essence of this decorative consecrated feast held on sacred festival grounds. In the Bali-Hindu religion, the making of ceremonial food and offerings is, in itself, an act of worshipping and honoring the gods. Traditionally, the Balinese gain karma by preparing food and offerings for a large ceremony, such as a mass cremation, which normally took one month in the past and carried with it a one-month gain of good karma.

Balinese food is distinctive among the leading cuisines of the world. Dedicated to the gods, this time-consuming, almost completely manual culinary art is inextricably bound to the islands Bali-Hindu religion, culture and community life. Rituals and ceremonies always escalate into large-scale ceremonial feasts. Balis most visual, color and taste sensations only appear at major celebrations as the ingredients are costly and an inordinate amount of preparation time is required. Exquisitely embellished ritual foods are prepared for life cycle rituals (ground-touching ceremonies, weddings, tooth filings and cremations), temple anniversaries and important religious holidays like Galungan-Kuningan. The family or community involved contributes materials and labor, and the dishes are cooperatively fabricated in the temple kitchen. Some dishes are prepared as religious offerings while others are to be shared and eaten communally afterwards by co-workers, friends, family and banjar (village association or hamlet) members who have helped with the hard labor. Special mini- rijistaafel platters with small portions of several foods, crowned with decorative woven bamboo basket covers or tutup , are prepared and served to VIP cokorda (Balinese royalty) in attendance. In accordance with local custom, meals for the other castes are presented on a round platter. Each tray artfully displays such treasures as nasi kuning (yellow rice with turmeric, peanut and spiced grated coconut) and vegetarian lawar (the traditional preparation of such vegetables as ferns or paku , egg and green beans mixed with coconut and spices).

Mass tooth filings may entail two months of preparation and the women of the compound have to prepare daily meals to sustain the armies of workers. Grand ceremonies turn the family kitchen into an ongoing neighborhood food production factory. Banana leaf-wrapped packets of food are also hand-delivered to distant family and friends following any major village ceremony, even in modern, bustling work-aday Kuta.

When the Mexican painter, traveler and amateur anthropologist Miguel Covarrubiass seminal work, Island of Bali , was published in 1937, it ignited the worlds love affair with Bali. Covarrubiass vivid impressions of a pre-modern, pre-tourist Bali included the first Western descriptions of traditional Balinese food and food culture. In his classic text, he described local feasts or banjar banquets and ceremonies in Bali in the 1930s: When the food is ready and the guests are assembled, sitting in long rows, they are served by the leading members of the banjar and their assistants. They circulate among them carrying trays with pyramids of rice and little square palm leaf or banana leaf dishes pinned together with bits of bamboo. These holders contain chopped lawar mixtures, sat lembat , babi guling , bebek betutu , and little side dishes of fried winged beans ( botor ), bean sprouts with crushed peanuts, parched grated coconuts dyed yellow with kunyit (turmeric ) , and preserved salted eggsalways accompanied by tuak , arak , and brem .

There is a strict gender division of ritual labor in Bali. The preparation of dishes that require sacrificial meats, from the slaughtering of the animals to the expert grinding of the spices, from the winding of the satays to the mincing of the turtle and pork dishes, is strictly a male responsibility because it is physically strenuous work. Ritual food is traditionally prepared at night as it has to be ready in the morning for ceremonies which often begin at dawn. Scores of men from each household gather at the bale banjar armed with large cleaver-like Balinese knives ( belaka ) and cutting boards to perform a sacred procedure known as mebat or ngeracik basa , the chopping of all the ceremonial ingredients. The spices are presented to them in woven coconut leaf baskets. The teams of men sit crosslegged on the ground on coconut leaf mats in two long rows facing each other, their chopping boards in between. Clad in traditional sarongs and sashes and wearing large antique silver or gold rings embedded with magical stones and potent protective powers, they mix and grind piles of pre-chopped spices. The men energetically smash shallots and garlic cloves, crush spices, scrape galangal and turmeric roots and hand-grate and shred dozens of freshly roasted coconuts for three hours on the evening before a ceremony. The tektek-tek sound of their knives on the cutting boards can be heard far away. This sound is an inescapable part of Balinese village life. When the spices are prepared and ready, the men go home for a few hours of sleep and return at 1 a.m. to butcher and prepare the animal meata whole sea turtle ( penyu ) in southern Bali, ducks or pigs in other parts of the island. The men boil organ meats to be skewered and grilled and prepare blood soup and pork tartare from 3 to 5 a.m. A jug of arak is often passed around to enliven the proceedings. Women are only allowed to wash salad ingredients, fry onions and assist with other basic preparation chores. They also cook the rice, prepare vegetables, make coffee, tea and rice cake refreshments for guests and helpers, and plait hundreds of coconut leaf offerings.

The megibung ritual ( megibung means having a meal together), a cultural feast of epic proportions, is still carried out in Bali, as largely unchanged customary practices continue to take precedence over modernity. The traditional megibung food feast originated in the eighteenth century during the time of the Karangasem kingdom in East Bali and is still widely observed in the villages. Beside being a tool of religious ritual and a communal gathering, the purpose of the megibung was also to ascertain how many troops were in the kingdoms army at that time. This traditional event is now held in order to build togetherness and reinforce friendship and brotherhood within the community. At the gathering, all participants are considered equalnone is rich or poor and none is educated or uneducated. The megibung is carried out at meal times during the laborious group process of organizing and implementing temple ceremonies and during life cycle rituals such as weddings. The early morning (36 a.m.) mebat procedure is the entrance ticket for the subsequent male only megibung feast, which takes place at the banjar before every large temple festivity, around 6 a.m. Holy cooking responsibilities are taken very seriously. The mebat men conscientiously chop ingredients pre-dawn for all the ceremonial food, special community portions for family members and ritual banjar chefs, and the upcoming megibung participants.