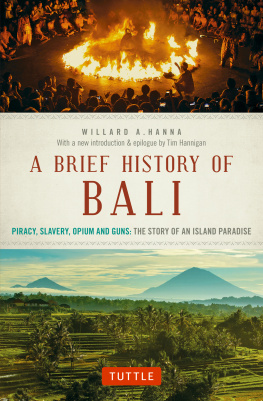

PROLOGUE

Blood and beauty

This is the morning of the world.

PANDIT NEHRU

The steady hum of political violence plagued theBalinese state probably through the whole course ofits history.

CLIFFORD GEERTZ

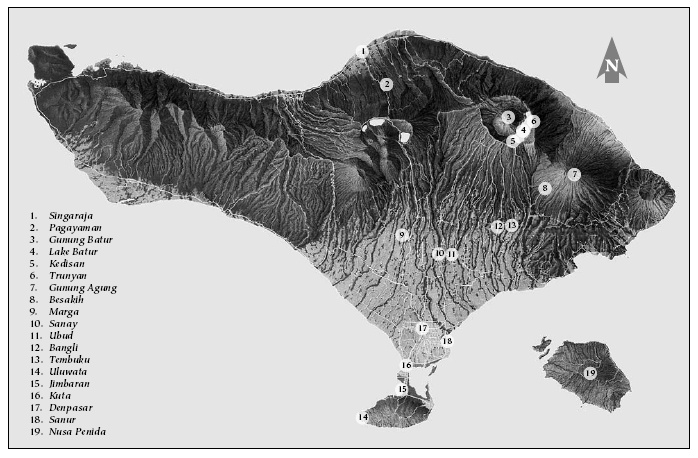

Mangku Meme, old, old woman with nut-brown face and ground-down teeth stained betel crimson, lives under the volcano on the shore of Lake Batur in the village of Kedisan. The lake was born after an eruption of Gunung Batur thirty thousand years ago left a deep depression, a caldera. Lake Batur is sacred to Dewi Danu, Hindu goddess of rivers and lakes, provider of irrigation water for the rice which has sustained Balinese people for centuries. It is a place for the sacrifice of animals goats and even great water buffalo drowned in rituals to placate the spirit guardians. It is a source of the holy water essential for ceremonies which thread through the lives of Balinese, binding them together.

A boat-ride across the lake from Kedisan is Trunyan, isolated under the caldera wall, where Wayan Ardana lives. He is twenty-eight years old, a fisherman and a virgin. Trunyan is one of the last refuges of the Bali Aga, the original Balinese, descendants of the animists who pre-dated the coming of Javanese Hindus of the Majapahit kingdom in the fourteenth century. For Wayan Ardana, Lake Batur is a source of sustenance and the centre of the world. Hidden in the village temple is an ancient statue, almost four metres high, the tallest traditional statue in Bali. This is the old Balinese god Ratu Gede Pancering Jagat, possessor of magic powers and defender of Trunyan, who has a powerful consort. Each year young men like Wayan, and adolescent boys who have passed a test for holiness, undergo a purification process in isolation for a month and seven days. They then perform the Barong Brutuk dance to celebrate the legendary wedding of Ratu Jagat to the goddess of the lake, Dewi Danu.

In Kedisan, old woman Mangku has her own gods: the Hindu trinity Brahma the creator, Vishnu the preserver and Shiva the destroyer and Bung Karno, Brother Karno, Sukarno, the flawed, charismatic first president of the Republic of Indonesia. The shrines of the trinity are in the small courtyard outside her home. Each day she prepares offerings for them, sitting cross-legged, quid of tobacco in cheek. In her nineties now, she has been doing this since she was a small girl, slicing and splicing coconut leaves to form a small basket, adding flowers, incense and betel and intricate decorations to make three canang sari, offerings fit for gods. Inside the house, there is a small room, smoke-stained, full of mysterious smells and watched over by the official photograph of Sukarno, taken at the height of his power. At times Mangku talks to his spirit. These are easy conversations: Sukarno was of the people importantly, he was half- Balinese and as in life he consulted mystics, it is fitting that in death he talks with Mangku, for she too is a mystic.

Gunung Batur, the volcano, often reminds Mangku and Wayan of the need for protection by gods and spirits. It grumbles and spits steam. But the black scars down its flanks to the caldera floor and the lake shore remind them also that prayers and offerings arent always enough. The volcano has erupted more than twenty times since 1800, most recently in 1994. In 1917, it roared out rocks, ash and lava. Down at the base of the volcano in Batur village, home of Ulan Danu Batur temple, which is dedicated to Dewi Danu, fearful people sent their prayers up to the gods and goddesses, but more than a thousand people died and more than sixty thousand homes and two thousand temples were destroyed. Then a lava flow stopped at the gates of the temple, so the Batur survivors put their lives together again. But in 1926 Gunung Batur erupted once more and the river of lava swallowed the village and all the temple but the highest shrine. This time the rebuilding of Batur and Ulun Danu Batur temple was done on the crater rim.

Mangku is known far beyond the shadow of the volcano. For decades she has taken part in festivals, a dancer, as most Balinese are, but an innovator too. One year she made a fan part of her costume and as quick as word of mouth, fans appeared in hands across the island. She has taken a role in distant ceremonies, for she is a priestess. She is shaman and maker of rain, healer of body and mind. Such a woman for all seasons is needed in Bali.

*

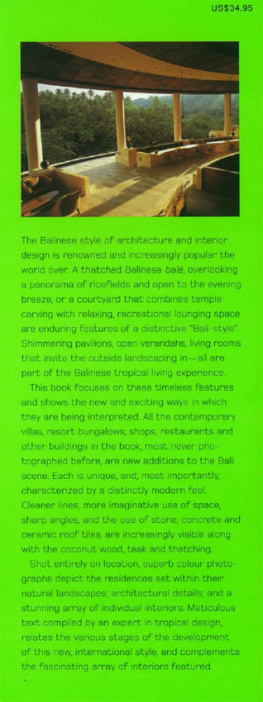

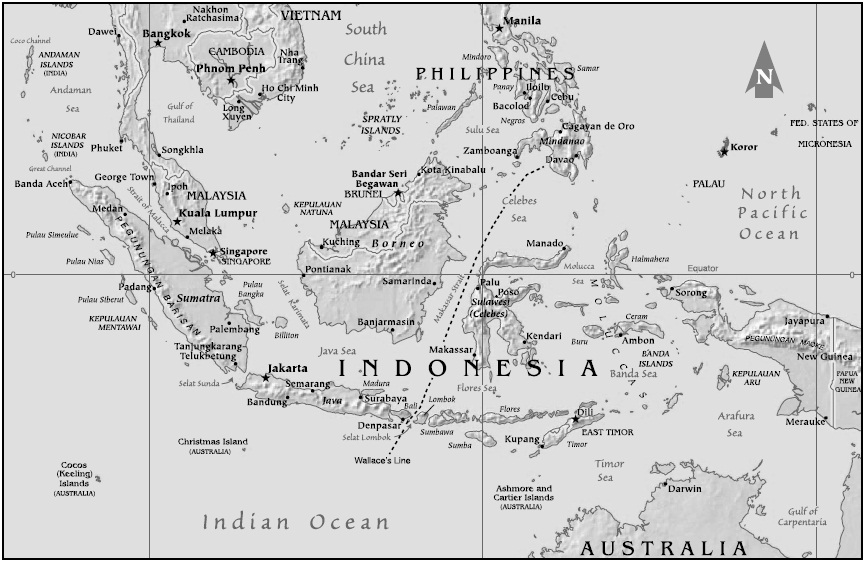

Bali of contradictions. Bali, beautiful by nature, but riding a geological fault line full of fury and primordial fire. Bali, dancing to the gamelan, going about its traditional business gorgeously dressed in gorgeously decked temples. Bali with long avenues of urban concrete ugliness, strung with powerlines and scented with pollution, where drug addiction grows and courier mules fl irt with the death penalty. Bali, sculpted by rice farmers, with its emerald-green fields turning to gold, water temples and ancient, intricate irrigation systems, now thirsty because of the demands of tourists. Bali, where terrible, evil Rangda the witch and the barong, the strange animal which represents goodness and which protects mankind, are more than masks and actors; where dancers fall into trance; where people can change themselves into leak, practitioners of black magic which can take the form of a monkey, a human, wind or light. Bali, where, as Alfred Russel Wallace a naturalist who developed the theory of evolution and natural selection coincidentally with Charles Darwin proclaimed, the Asian sphere ends and the Australian sphere begins (for, as a modern biologist put it, one is a world of tigers, the other a world of kangaroos). Besieged Bali, a Hindu island in an Islamic sea, desperate to maintain its culture against the waves which wash in from the rest of Indonesia and from the West. The Bali which happily believes marvellous myths about itself and which refuses to face a terrible reality. Bali, paradise? Bali, paradise lost?