[CHAPTER 1]

Kaja and Kelod

SPATIAL AND SPIRITUAL ORIENTATION

IN THE WEST ONE IS ACCUSTOMED TO A WORLD BUILT UPON OPPOSITES: sacred and profane, positive and negative, constructive and destructive, male and female. The Balinese also recognize this polarity, which they call rwa bineda. But in the Judeo-Christian tradition, these opposites are presented as mutually exclusive choices: either one does/is good, or one does/is evil. In the Hindu-Balinese scheme, this division is neither so stark, nor at all exclusive. And it includes what can be considered a third position, "center," which balances the other two.

In Bali, the position of mankind is one between good and evil or, more appropriately stated, in a state of coexistence with them. Mankind's job is not to destroy evil. Nothing in the teachings of Balinese Hinduism requires or even mentions this. Evil is a part of the whole, and good is a part of the whole. Neither can exist without the other. Instead, the life of any Balinese is devoted to maintaining a balance between these opposing forces maintaining an equilibrium so that neither gets the upper hand. This notion of three forces, overlapping and interdependent, the three together constituting a whole, lies close to the center of Hindu theology. Even the most casual tourist learns of the Hindu triad Brahma, Wisnu, and Siwa. But this is only one of the myriad tripartite classifications that organize Balinese society. This grouping by threes, or tri hita krana, governs ideology and activities as grand as cosmology, and as humble as building a toilet.

For most busy Westerners the airport is where the freeway arrow points; north is where you ski in the winter; "up" is a button on the elevator. We don't assign special importance to orientation, except possibly to choose a house for its nice view. Direction is instrumental in the West. "How do I get to the hospital?" Answer: "Head down the street that way (pointing), and turn that way (pointing)." And except to the extent that it enables us to get where we"re going, a sense of direction means little to us. But orientation is exceedingly important to the Balinese. In Bali, a direction describes a vector not just in physical space, but in cultural, religious, and social "space" as well. As a result, every Balinese seems to possess a built-in sense of direction. And if for some reason this feeling is lacking, the individual is visibly uncomfortable and disoriented.

A few years ago my friend and associate I Wayan Budiasa came to live at my home in the United States. He arrived about noon in early winter when the sun was low and in the south. From then on, that direction was east to him because in Bali, just a few degrees south of the equator, the sun is near the horizon only at sunrise and sunset. He quickly learned, intellectually, that this direction was south, not east, but he felt that it was east, and no amount of intellectualizing could change that first visual impression. He learned to say south, but he still felt east. It bothered him for the entire two years that he lived in the United States.

ORIENTATION IN BALI begins with the sacred mountain, Gunung Agung, which stands 3, 142 meters high in the eastern central part of the island. Gunung (Mount) Agung is the dwelling place of the Hindu gods. Toward the mountain is called kaja. Because Gunung Agung is in a fairly central location, kaja is a variable direction. It is north for inhabitants of South Bali and south for those who live in North Bali. Whether north or south, it is always "up," the sacred direction toward God. Antipodal to kaja is kelod, seaward, toward the lower elevations and away from the holy mountain. Kelod is "down," less sacred than kaja, even impure. The second-most sacred direction, after kaja , is kangin, "east," the direction from which the sun, an important manifestation of God, rises. Kangin' s opposite to the west, kauh, is correspondingly less sacred.

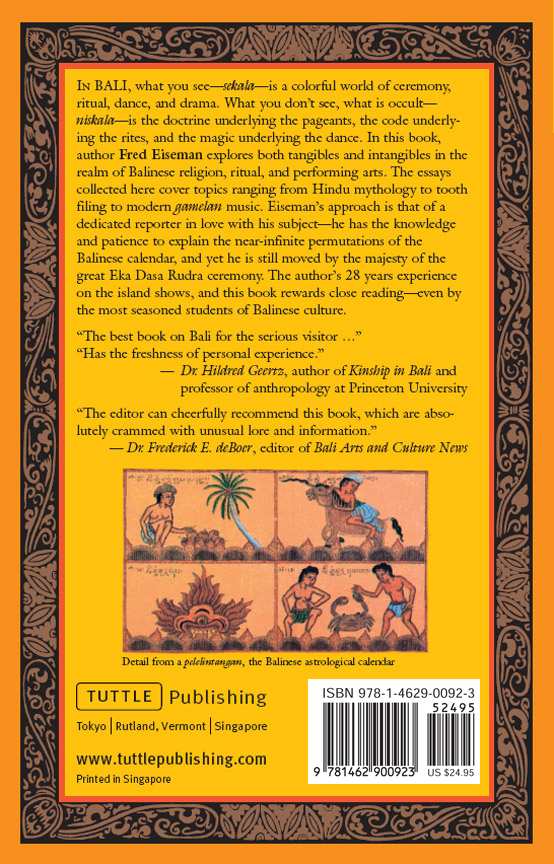

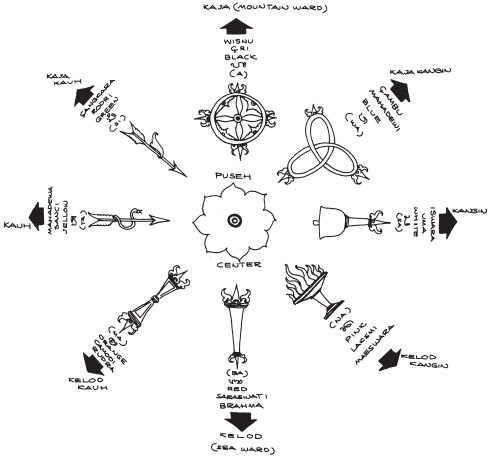

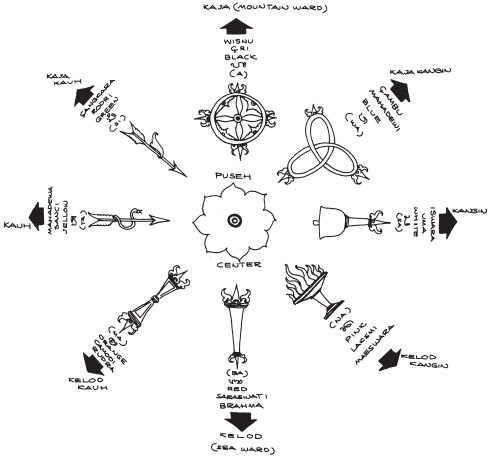

The eight compass directions consist of four cardinal points kaja, kangin, kelod, kauh and their intercardinal divisions kaja-kangin, kelod-kauh, etc. To these are added the position, center. In each of these nine directions dwells a separately-named aspect of God, each aspect having its associated color and characteristics. Sometimes the symbolism is extended to cover all three dimensional space by adding two more directions, up and down. For example, once every hundred years an enormous islandwide ceremony is held to exorcise evil forces, to drive them off into the eleven directions of all space. The name of this ceremony, Eka Dasa Rudra, comes from the Sanskrit expression for eleven, eka dasa. (See CHAPTER 21.)

This kaja/kelod, sacred/profane, high/low concept is deeply ingrained in the Balinese psyche. Villages are aligned kaja-kelod. The cemetery and the temple called Pura Dalem, dedicated to Siwa, or to his wife, Durga, are located at the kelod end. And the villagers locate the Pura Puseh, the temple dedicated to Wisnu, on the kaja, upslope end. Each temple, and there are tens of thousands of them in Bali, is itself oriented kaja-kelod. The most sacred inner part of the temple, containing the holy shrines, is kaja and higher than, and divided by a gate from, the more secular courtyards of the temple complex.

Every house compound is oriented kaja-kelod. The family temple is in the most sacred position, kaja-kangin. The head of the household lives in the most kaja building in the compound. Everyone sleeps with his or her head toward either kaja or kangin , the sacred directions for the head that together are called luan. The directions for the feet, kelod or kauh, are called teben. One would not put a door or a clothes closet on the luan side of the bedroom. The kitchen and granary are kelod. Furthest kelod, often kelod-kauh, are the animal pens and the garbage dump.

THE BALINESE COMPASS, WITH DIRECTIONAL SYMBOLISM

To understand orientation on Bali, one must make what may at first seem to be a very fine distinction between "direction" and "place." Since kelod, towards the sea, is the direction away from the seat of purity, the assumption is sometimes made that the sea is the least sacred place of all. This is an error. In fact, the Balinese consider the sea to be a place of exceptional purity. Directions are relative, not absolute. Kelod is an impure direction. A man dumps garbage and keeps his pigs at the kelod end of his house compound. His family temple is at the kaja-kangin corner. Yet this same man's neighbor, who lives directly kaja, dumps his garbage and keeps his pigs at the kelod end of his house compound just over the dividing wall from the most sacred part of his neighbor's house.

The daily attitudes and behavior of the Balinese reflect this highly oriented, directional space. In situations in which Westerners would point or say "left" or "right," or "here" or "there," the Balinese use compass directions. If a group of men are carrying a heavy load that must be placed in a particular spot they will shout to each other: "A little more kaja now a bit kangin there, now, set it down." If you visit a friend and are invited into his home he may say: "Come kaja and sit down next to me in this chair to the kauh" When giving directions for travel a Balinese will always say something like: "Go a little farther kangin, turn kaja at the crossroads, and you will find his house on the kauh side of the road."