Acknowledgements

While a vast amount has been published about Bali, it tends to divide very clearly. There is the generaloften too-generalpopular or travel writing, mainly based on rehashing or republishing works from the 1930s, and inaccessible academic work. This book is designed to bridge the gap between the two, and to bring to a wider audience important scholarship on Bali.

In carrying out this task I need to apologize most of all to Professor James A. Boon, Dr. Henk Schulte Nordholt, and Dr. Michel Picard, whose territory I have ventured onto in order to draw together the various strands of Balinese cultural history. Besides these three, I only have space to thank a few of those in Bali or engaged in the study of Bali who have influenced this work: Drs I Putu Budiastra; Professor Linda Connor; Professor Hildred Geertz; Dr. Jean-Francois Guermonprez; Professor H. I. R. Hinzler; Professor Mark Hobart; Dr. Douglas Miles; I Nyoman Mandra; Ida Bagus Pidada Kaot; Dr. Stuart Robson; Dr. Raechelle Rubinstein; John Stowell (particularly for very detailed criticism of the original book); Dr. David Stuart-Fox; Associate Professor Carol Warren, John Wilkinson, and Professor P. J. Worsley. In revising the original book, I benefitted from the research of and discussions with Barbara Bicego, Leo Haks, Laura Noszlopy, Dr. Nyoman Darma Putra, Dr. Graeme MacRae, Degung Santikarma, and Dr. Agnieszka Sobocinska. Sadly many of the people who profoundly affected my view of Bali are no longer alive: Professor I Gusti Ngurah Bagus, Professor Anthony Forge, Drs B. Joseph, I Ktut Kantor, Anak Agung Kompiang Ged, Dr. Barbara Lovric, Ratu Dalem Pemayun, I Gusti Mad Deblog, Ida Bagus Putu Ged (Pedanda Batuan), I Mad Kanta, Mangku Mura, Pan Seken, Dalang Ktut Rinda, and Ida Bagus Mad Togog.

I owe a great debt to Professor Alfred McCoy who, as series editor, came up with the original idea for the book, helped relieve me of the boring aspects of my academic style, and shaped the nature of this book. Thanks also to Dr. Ian Black and Professor John Ingleson who provided all kinds of support to see me through 1988. Of the many staff in the school of History at the University of New South Wales, Libi Nugent and Shayne Sarantos in particular helped with the important material details of writing, and Mark Hutchinson with miscellaneous computer assistance. Dr. Kathy Robinson provided interest and encouragement. Hazel and Emma Vickers have lived with Bali for many years, and illuminated my own understandings of the island. Hazels editorial work has also been vital in updating the book.

The original illustrations for this book were funded by a Special Research Grant from the University of New South Wales. Deborah Hill provided the photographs on pp. ) are unknown.

Photograph on p. courtesy of Ida Bagus Surya Darma and Kadek Jango Pramartha.

C HAPTER O NE

Savage Bali

There is much that has been forgotten in the worlds image of Bali. Early European writers once saw it as full of menace, an island of theft and murder, symbolized by the wavy dagger of the Malay world, the kris. Although the twentieth-century image of the island as a lush paradise drew on the earlier writings about Bali, these were only selectively referred to, when they did not contradict the idea of the island Eden. The overall negative intent of most of the earlier western writings about Bali has been discarded.

From the first western encounters with Bali at the end of the sixteenth century until the first decades of the twentieth century, one image of Bali has predominated: its warlike image. This image has gone through at least three stages. Initially, from the end of the sixteenth century, it was part of a very positive idea of Bali as an exotic place of eastern bounty and strange Hinduism. From the mid-seventeenth century slave trading made Bali both appealing and threatening, a place to acquire useful females, but where male slaves showed a temperament that made them rebellious. In this period Bali became a more dangerous place, somewhere wild and untamed, where Europeans were loath to go. The beginning of the nineteenth century saw the first steps towards the abolition of the slave trade, at the same time as a new phase in Balis image began. Bali remained warlike and threatening as it resisted European colonization, but added the attractions of a culture that gave its menace a civilized edge. European powers saw it as their mission to tame the wild Bali.

A Hindu Corner of an Islamic World

Cornelis de Houtman discovered Bali in 1597 as leader of the first Dutch expedition to the East Indies; 300,000 Balinese and a considerable number of other inhabitants of the Indies were not really so surprised to hear that there was a Bali, nor were the Portuguese sailors and missionaries, and the English privateer, Sir Francis Drake, who had preceded de Houtman. This Dutch discovery of Bali came at a time of religious war in Europe, war which made the Dutch and other Europeans see all conflicts in religious terms as they tried to force their way into the area. Balis image at this time was largely a product of these European preoccupations and policies.

In the sixteenth-century, as now, Islam was the great enemy of the Christian faith. To these Europeans Bali was a religiously-oriented island, a Hindu outpost in a sea of Islam. It overflowed with the tropical wonders of the Indies, and was controlled by a sumptuous ruler surrounded by the military signs of power and wealth. De Houtman was an adventurer of his day, charged with opening up the lucrative spice trade of Maluku, the Spice Islands, to the Dutch. He was therefore an enemy of the Catholic Spanish and Portuguese, and a stout Protestant, as were most of his Northern European countrymen. Like other Protestants he was opposed not only to the Papists who had ruled the Low Countries, but also to Islam. The book that described de Houtmans journey to the rest of Europe was reprinted and adapted many times, and in different languages. In accordance with the scientific standards of the day it presented a summary of the peoples, natural produce and ecology encountered on the journey from the harbor of Amsterdam to the Spice Islands. Its images came to have a central place in Northern European thinking about the Indies.

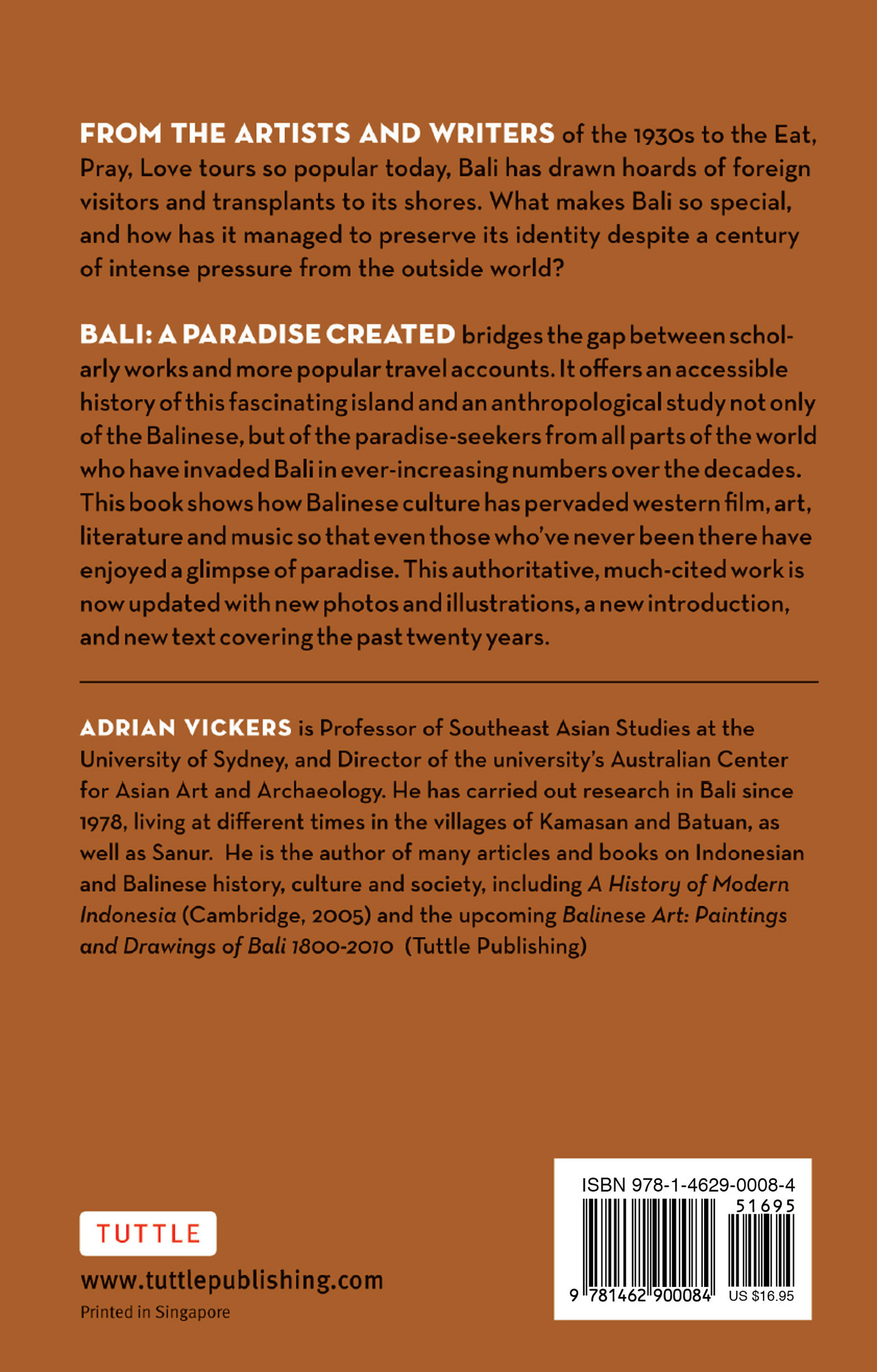

The king of Bali in 1597: The magnificence of Balinese kingship as seen by the Dutch in the rare first edition of the account of the first Dutch expedition of the East Indies.

Bali in that book was a counter to the hostile world of Islam, for throughout their voyage de Houtman and his men had encountered Islamic kingdoms. Against the Muslim kings, the Moors and Turks, de Houtmans book announced the discovery of a friendly Heathen kingdom, by which he meant a Hindu kingdom, Hinduism being something Europe had been familiar with since the days of Alexander the Great. In the first edition of the book there were just a few illustrations, and only two were of kingsa Muslim king from Sumatra, and Balis Heathen or Hindu king.

Balis description bespoke wealth and luxury. The Dutch, who did not have a proper king at the time, and who thus had a unique perspective on the role of kingship in the state, were fascinated with the king of Bali. The accompanying illustration in the first edition of the book showed the king half-naked in a splendid ox-cart, surrounded by his bodyguards, who were armed with gold-tipped spears and blowpipes. The bodyguards represented both a display of subjects and the promise of violence inherent in any interactions between foreign nations. The backdrop was one of rice fields and the other produce of natures tropical bounty, the abundant wealth that made the picture an invitation to trade in the Indies.