The Southeast Asian House

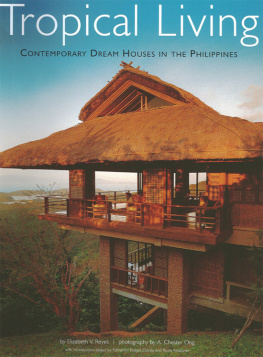

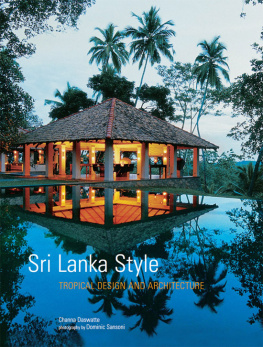

All of the houses appearing in this book are contemporary in design, yet share common features which transcend the mere fact of their tropical situation. This is because they are, to varying degrees, part of an ancient and common architectural tradition, one that may be called the style of the traditional Southeast Asian House.

I n order to gain an understanding of today's tropical houses, it is necessary to take a look at the history of the regionboth cultural and architectural. Whilst many of these contemporary buildings have modern features, such as up-to-date sanitation, electricity, high-tech kitchens and so on, they borrow numerous elements of local design. By tracing the development of Southeast Asian vernacular building traditionsand indeed it is very much a living tradition, found in countless places throughout the regionone comes to appreciate today's creations all the more.

One thing is certain: Southeast Asia has a very ancient building tradition, one that is characterized by the use of natural materialstimber, bamboo, thatch and fibreand a post and beam method of construction. Houses are traditionally designed round a rectangular wooden framework consisting of vertical posts and horizontal tie-beams, supporting a pitched roof with gable ends. The living floor is raised off the ground on pile or stilt foundationsthe former are sunk into the ground, while the latter typically rest on stone foundation slabsand the roof ridge is often extended at either end to create outward sloping gables. The walls do not constitute part of the load-bearing structure as such, but rather consist of panels of wood, thatch or plaited bamboo laths, which are attached to the main framework; the whole ensemble is then put together without nails, using mortis and tenon joints and wooden pegs (see page ).

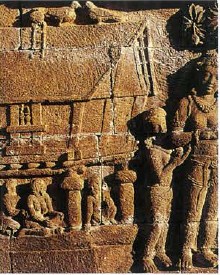

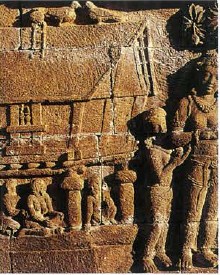

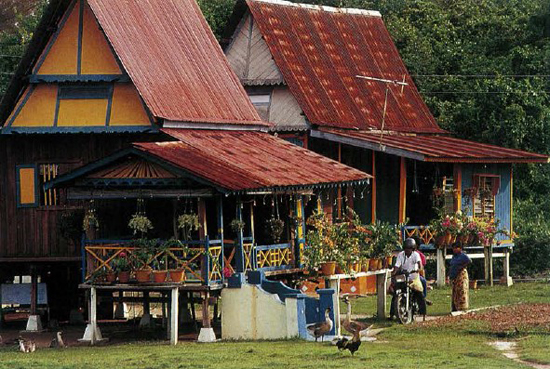

This, then, is the archetypal Southeast Asian house. Exceptions, where they exist, can be linked to historical circumstances. For example, the ground-built houses of Java and Bali probably arose during Indonesia's Classical Era (5th to 15th centuries) when there were close cultural contacts with India where this is the standard practice. Even in these instances, one still finds that the traditional rice barn in Bali is a typical Southeast Asian post and beam structure, while Classical Javanese temple reliefs (see above, Borobudur) depict house types that closely resemble contemporary stilt dwellings from Sumatra (see right, a Minangkabau house from west Sumatra).

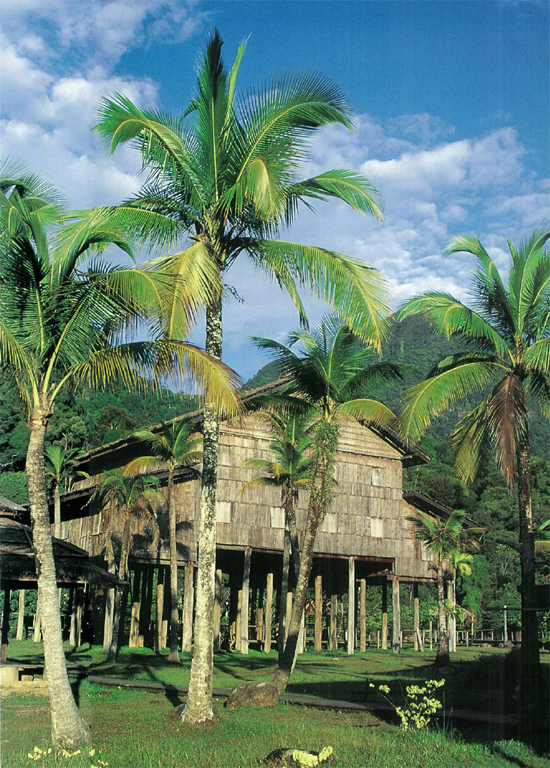

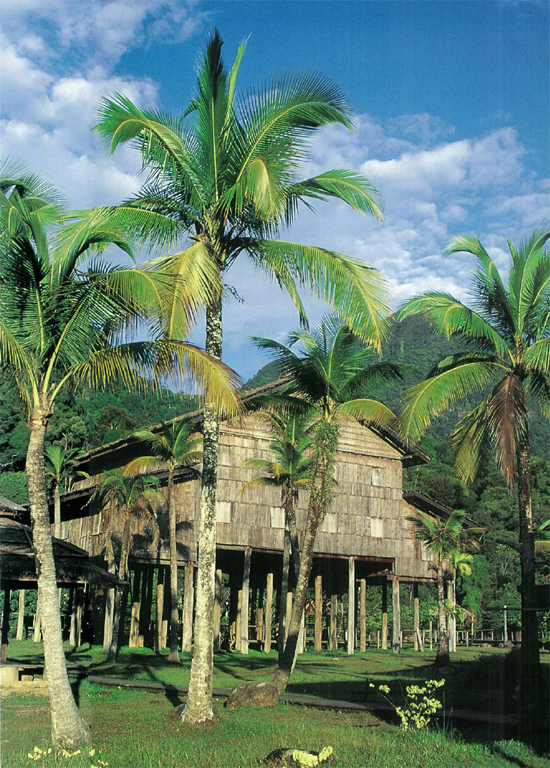

Longhouses were once a ubiquitous feature of the Bornean landscape. Raised high on pile foundations, they were literally home to an entire community. The basic pattern was everywhere the same, namely a series of family apartments arranged side by side which opened onto a gallery, or covered verandah, running the full length of the building. Much of daily life was enacted in this public space with the family only retiring to their rooms to eat and sleep.

The building shown here is a section of a Melanau long-house as reconstructed by the architect Edric Ong for the Sarawak Cultural Village near Kuching, Malaysia. Most Melanau today have embraced a contemporary lifestyle and there are no Melanau longhouses left in existence. This structure, which was constructed with reference to old photographs and other archival records, was assembled using traditional building materials including ironwood house posts, bark wall panels and nipa-palm thatch.

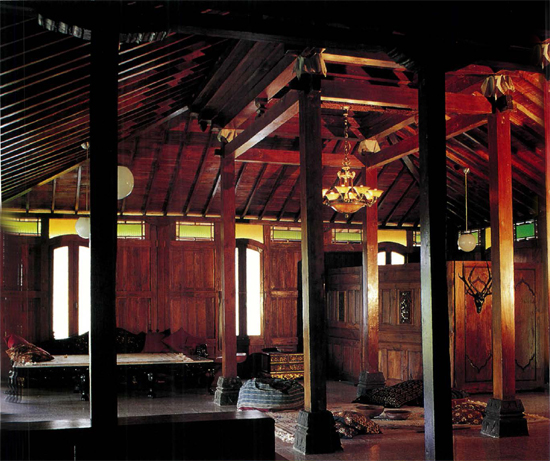

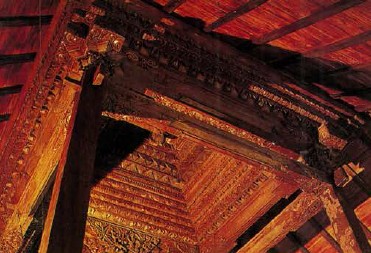

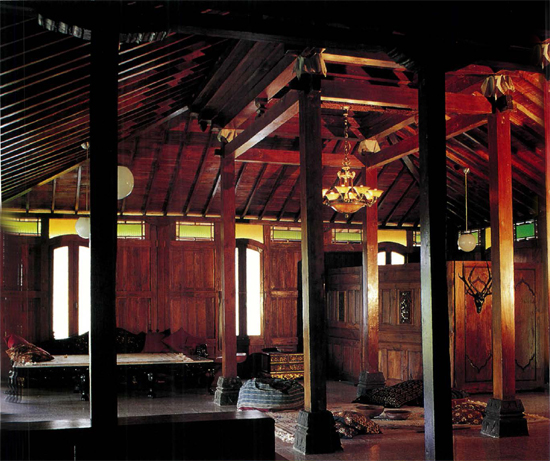

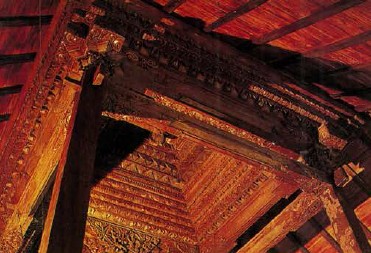

Interior of a Javanese nobleman's house. The four central columns (soko guru) supporting the roof, are topped by a unique structure called the tumpang sari. The latter consists of several layers of beams which step in towards the centre of the building, to create a vaulted ceiling (left). In symbolic terms, this is the most sacred part of the house, situated directly beneath the soaring central section of the joglo roof which announces the aristocratic connections of those who dwell within.

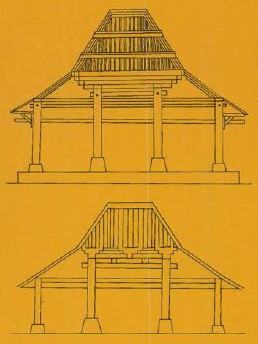

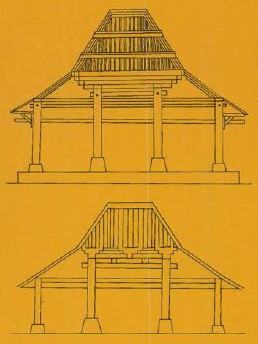

Drawings depicting the design of a typical Javanese pavilion or pendopo.

The suitability and versatility of this architectural form in relation to the environment is obvious. Because the house is raised from the ground, it affords its occupants protection from dangerous animals and the seasonal inundations associated with living in a tropical climate. Equally importantly, the elevated living floor catches ambient breezes, whilst allowing a current of cooling air to pass beneath the floor. The gable ends of the pitched roof similarly direct breezes through the high open space, whose tunnel-like properties ventilate the house from above.

At the same time, the use of natural building materials with low thermal propertieswood, bamboo and thatchcombined with lightweight construction techniques (minimal mass and many voids) mean that little heat is either retained within, or conducted into, the building. Low walls and deep eaves reduce the vertical surfaces exposed to solar radiation while reducing glare inside the house. In many cases, grilles and louvred fenestration further fragment the sunlight entering the building. This results in good illumination, but also disperses the intensity of the sun's rays.

In all these respects the Southeast Asian house presents an admirable solution to the environmental problems posed by living in a hot, humid climate, subject to seasonal monsoon rains. But it should be noted that the housein the past, as todayis much more than simply a dwelling place, somewhere where people eat, sleep and take shelter from the elements. Rather, it is a symbolically ordered structure through which key social values and cultural orientations are expressed. Several of the home owners featured in this book speak of the karma, or spiritual qualities, of the houses they live in, and in many Southeast Asian cultures the house is traditionally conceived as a "living" entity, animated by a soul or spirit essence.

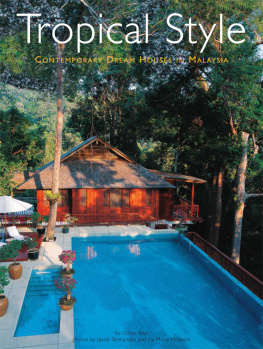

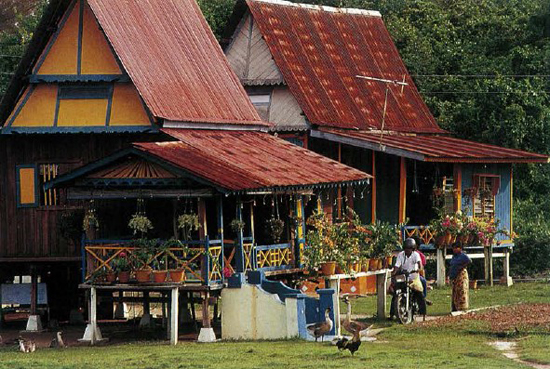

Traditional Malay houses in the West Malaysian state of Malacca.

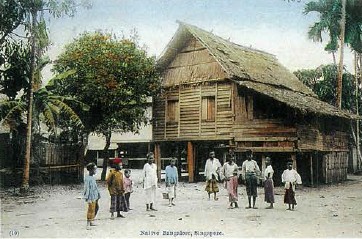

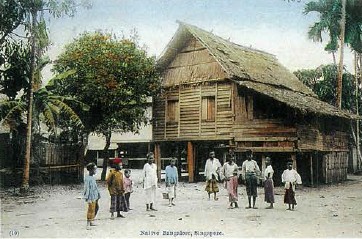

An old Singapore postcard depicting a Malay village in Singapore at the turn of the century.

Malay houses are always built on stilts (see drawing by Julian Davison below). In the region of Malacca they are distinguished by the addition of a grand staircase of Chinese origin. This staircase is usually decorated with the same bright tiles imported from Europe that were also used in Chinese shophouses.