W HEN I WAS ASKED TO WRITE the Foreword to this book, I immediately accepted. Having had the privilege of meeting James Laxer and discussing Acadian and Canadian issues with him a few summers ago, I was delighted to learn that he was writing a book about Acadie.

Since the 1990s, numerous works on Acadie and on Acadian studies have been written by both North American and European scholars in French, English and more recently in German. James Laxers contribution to this impressive body of work is unique and is a witness to his excellent reputation established by his previous works. His analysis of Acadies past and present is both pertinent and original through his examination of the historical and contemporary journeys of Atlantic Canadas Acadians and their Cajun cousins in Louisiana.

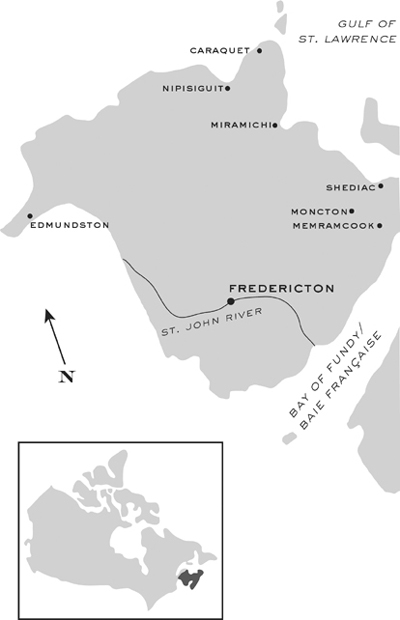

Another original contribution of James Laxers work is in its view of contemporary Acadie. This book focuses on the Acadian community in New Brunswick, but the way in which Laxer examines the Acadian soul and the shifting identities in present-day Acadie can also be applied to the other Acadian communities of Atlantic Canada. Laxer has skillfully described the Acadian communitys historical and contemporary quest for a homeland.

It is my wish that the great interest and pleasure I experienced by reading this book will be shared by others so that they can also discover one of North Americas oldest societies whose resilient identity is a testimony to their enttement.

INTRODUCTION

ACADIE IN QUESTION

IT WAS THE LAST DAY for the Acadians at Grand Pr, the last day for them to live normal lives in the community they had built over the past century. On the morrow the soldiers would arrive on British ships. Their commander had received instructions from Charles Lawrence, the acting governor of Nova Scotia, to forcibly remove the inhabitants, burn their houses, churches and mills and lay waste their fields. It was late September 1755 and much of the crop had not yet been harvested. But on the eve of the coming of the ships, the people of Grand Pr had no reason to fear the onset of winter. Over the generations, Acadians had learned the hard lessons of life in a new land whose winters were much more difficult than those in the region of France around La Rochelle from which many of the first settlers had come. Their homes were built for warmth, with wooden walls that were filled in with stone to provide insulation.

On their fertile marshland fields, close to the sea, the farmers of Grand Pr raised ample crops and livestock. To their diet, they added game and fish and wild berries. They were a largely self-sufficient people, although they conducted vigorous trade with New Englanders that provided them with goods they couldnt produce themselves.

Once the crops were off the lands, the Acadians could turn their minds to other things during the coming cold months. Most weddings in Grand Pr were celebrated between late October and February, the period when the demands of harvesting and planting were in abeyance. This was a time as well for preserving food, and making furniture, tools and toys for the children. It was a time for celebration and enjoyment. And it was just around the corner.

Grand Pr was the largest of the settlements around the shores of the Baie Franaise (Bay of Fundy), the homeland of a new and distinctive people. The original settlers had left France for Acadie for a variety of reasons. Ambitious ones had come with the hope of making it in the fur trade or the fishery. Others came in search of adventure in a new age that offered Europeans the means to emigrate. Some sought escape from the strictures of French society, and others wanted to be freed from the vicious religious wars that devastated La Rochelle and other parts of France in the early seventeenth century.

Like other Acadian settlements, Grand Pr was made up of numerous small hamlets, where the members of extended families lived close to one another. The Acadians had branched off from the society of their original French homeland and had developed a way of life that set them apart from the French of France, as well as from the French Canadians who lived along the banks of the St. Lawrence River. The Acadians of Grand Pr had developed close ties with the Mikmaq of the region and there was a considerable amount of intermarriage between the two peoples. In Grand Pr and other settlements, Acadian children, Mikmaq children and children of mixed race all played together.

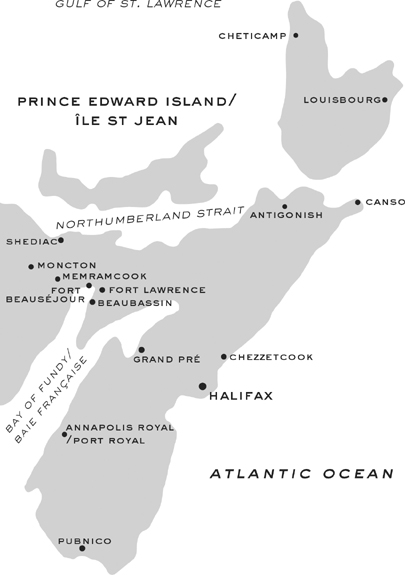

Prior to the deportation, the word Acadie referred to a territory that was repeatedly fought over by the empires of France and England. (While some believe the name Acadie derives from the Greek Arcadia, which symbolized an ideal land, others think it comes from an aboriginal word, perhaps the Mikmaq word Cadie, or the Maliseet word Quoddy. Both words connote a piece of cherished land.)

While the precise boundaries of Acadie were often in dispute, its broad shape was clear. Acadie included the territories of the present-day provinces of Nova Scotia (including Cape Breton Island), New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. Lured by the warm summer weather into believing that all would be well, the French established their first settlement in what was to become Acadie in 1604 on the le St. Croix, a small piece of land in the present-day state of Maine, located right next to the border of New Brunswick. The first winter was tragically disillusioningover half of the men in the tiny settlement perished. The following year, the French expedition abandoned the island and moved across the Baie Franaise to the territory of present-day Nova Scotia, establishing the outpost of Port Royal.

Acadie has always been a tough territory on the northern edge of the temperate lands of North America, never an Arcadia, and vastly unlike the France from which the Acadians came. The new people developed their uniqueness in a morose and lonely setting, a land of dark green forests with only marginally decent agricultural prospects. Peninsular Nova Scotia, the homeland of most Acadians before the deportation, is a tough, unyielding, spiny territory that remains almost impassable in places, even in our time.

For the Acadians, the highway of hope, life, culture, song and freedom has always been the sea. The sea linked tiny settlements with one another, and the sea brought a good life for the Acadians, who soon grew into a people who mastered the fishery, the commerce of the region, and unlocked the way to farm the marshy lands next to salt water. But if the sea brought prosperity and communication, it was also the highway of war for those who often descended on Acadian communities to pillage and burn, and in the end to destroy their settlements and force them into exile.