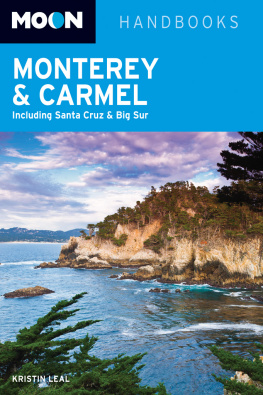

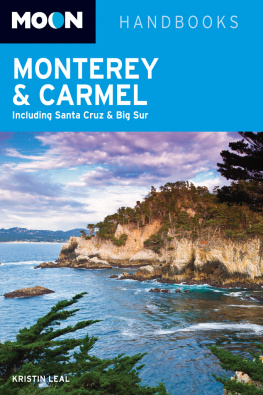

Monterey Bay and Monterey Peninsula are located 120 miles south of San Francisco, 60 miles southwest of San Jose, and 345 miles north of Los Angeles. A multitude of environments and climates makes up this fascinating stretch of coastline from the Santa Cruz Mountains down to Morro Bay.

The rural inland region of Monterey County has fertile farmland and rows of vineyards. Redwood forests tower in both Monterey and Santa Cruz Counties. Big Sur and Santa Cruz are known for backcountry hiking and biking, and all along the incredibly scenic coast, the surf is up year-round.

The climate of the Monterey area varies from season to season and from place to place. On a daily basis, inland microclimate areas differ dramatically from the peninsulas seaside climate. On the coast, you can count on cool dry summers, wet winters, and warm falls. More often than not, summer weather is foggy and a bit chilly, especially in the morning and late afternoon. Temperatures tend to be in the mid-60s. The best weather on the coast is in September-October. As the children return to school, the heavily visited spots quiet down, and daytime temperatures warm up to low 70s. Winter is the rainy season and lasts November-April, with average temperatures in the low 50s. Heavy storms on the Pacific Ocean throw down substantial amounts of water in a short time, and Santa Cruz usually gets hit the hardest. The yearly average temperature in Monterey County is 57F with 19 inches of precipitation annually. The coastal climate is usually a bit windy, moist, and foggy. The southern reaches of the Central Coast are normally warmer than farther north, both in the air and in the water. The inland region around Salinas is noticeably hotter and dryer, with coastal winds rolling over the neighboring coastal mountains.

SAN ANDREAS FAULT

The San Andreas Fault, the most accessible fault line in the world, is a vivid example of active plate tectonics. It is a sliding boundary or transform fault between the North American Plate and the Pacific Plate that slices California in two from Cape Mendocino in the north through the Mexican border. The plates are slowly moving past each other in opposite directionsa couple of inches per yearto create complex landforms all along its mighty rift.

When these plates shift lock against each other, the pressure becomes too great, and they break free with movement of a few feet at a time. This seismic action sends massive vibration waves in every direction, causing an earthquake. Along with many other fault lines, this is why California is prone to so many quakes; the state is slowly being dragged apart, and sometimes you can feel the rip.

The fault is thought to be about 28 million years old and has moved rocks from great distances. Geologists have found evidence of this movement at places like the Pinnacles National Monument in Monterey County. The Pinnacles themselves are only half of a massive volcanic complex; the other half is known as the Neenach Volcano and sits about 200 miles southeast, in Los Angeles County.

Several environmental issues are important in the Monterey area, but the hot topics have to do with sustainability, protection of the marine sanctuary, land usage, and a general focus on everyday green practices. Monterey Bay is in a National Marine Sanctuary (www.montereybay.noaa.gov) that reaches from Marin County in the north down to Cambria. The federal government and the local population are focused on protecting this treasured environment. The Monterey Bay Aquarium (www.montereybayaquarium.org) is also a major environmental advocate in Monterey County, promoting seafood sustainability, the marine sanctuary, and other things we can do to preserve the environment. Land Watch Monterey County (www.landwatch.org) is a local nonprofit organization focused on land management. California State University, Monterey Bay, has created a website known as Environmental Issues and Groups (www.agriculturaleducationandtraining.org/environmentalissuesandgroups) with a broad range of resources on industry and trade, educational originations, community groups, and companies.

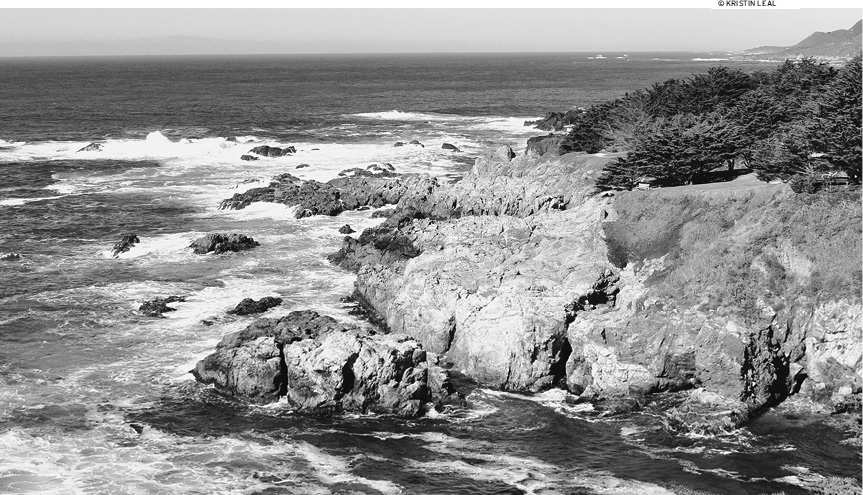

Throughout Monterey County, Santa Cruz County, and the northern part of San Luis Obispo County, the variety of flora reflects the diverse ecosystems that exist in this region. Found exclusively on the Monterey Peninsula is the Monterey cypress. There are only two natural groves of Monterey cypress today, one in Monterey and the other near Carmel in Point Lobos State Natural Reserve. These groves were once part of a large cypress forest that stretched all along the Central Coast 2,000 years ago. The Monterey cypress is a rugged tree that lives in the harsh ocean-side climate. The trees conform to the pressure of the wind and tend to grow with flat tops and twisting limbs.

Monterey pines are native to the area and grow in groves on the rolling hills and slopes of Monterey, Santa Cruz, Ao Nuevo, Cambria, Cayucos, and Morro Bay. Today, Monterey pines are among the most popular ornamental trees in the world, grown for both landscaping and commercial cultivation. Monterey pines are hearty with fissured brown bark and limbs covered with sappy pine needles. They are likely a cousin to the Jeffrey pines of the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

The bishop pine, also known as the prickle-cone pine, is commonly found throughout Pacific Groves Huckleberry Hill, along the Santa Lucia Range, and into San Luis Obispo County. Bishop pines look like a smaller sibling of the Monterey pine.

The knobcone pine is another local pine species named after its knobbed pinecones. These trees like to root in dry rocky mountain soil, and you will most likely encounter them in the steep terrain of Big Sur and the northern part of San Luis Obispo.

Groves of nonnative eucalyptus trees grow along the shores of Santa Cruz and Capitola, and inland along Highway 156 near Hollister, Pacific Grove, Palo Colorado Canyon, and south throughout Morro Bay. These tall trees, with curling bark and feather-like leaves, are not difficult to pick out; their refreshing scent and unique appearance instantly give them away.

There are several different species of oaks in this area, including the California live oak, black oak, and the tanbark oak. Oak trees are mostly seen in the inland regions and near the coast on wide grassy hillsides. You can find them on the chaparral hills of Carmel Valley and Salinas Valley, on the meadows and open hills of Big Sur, throughout the Santa Lucia Mountain Range, and down to Morro Bay.

One of the rarest oaks growing along Californias Central Coast is the pygmy oak, unusual and tiny trees seen along the southern stretch of the Morro Bay Estuary in the El Morro Elfin Forest. They resemble common oak trees in miniature size, 4-20 feet tall, and grow only along the California and Oregon coast.

You cant talk about trees on Californias Central Coast without talking about the coastal redwoods. There are two large redwood forests in this area, one in the Santa Cruz Mountains and the other in Big Sur. Both are part of the same chain of redwoods and are all continuously connected through their root systems. You can wander among the big trees of Santa Cruz in Big Basin State Park and Henry Cowell State Park. The redwoods of Big Sur grow throughout the region in the Los Padres National Forests Ventana Wilderness, Andrew Molera State Park, Big Sur State Park, Bottchers Gap, and several other federal and state parks along the coast.

The diversity of flowering plants in Californias Central Coast is magnificent. During spring, Pacific Groves shoreline ignites in brilliant magentas as the ice plants bloom, clinging to the sides of steep cliffs. Saffron-colored California poppies bloom in clusters along the inland reaches of Carmel Valley, down Highway 1 into Big Sur, and north of Santa Cruz along the curving coast. You will sometimes come across whole fields or hillsides full of brilliant poppies, but most of the time tiny groupings are found here and there. Huge yellow lupine bushes can be found all through Big Sur and in the meadows of Andrew Molera State Park. Purple lupine lines Highway 68 toward Salinas every year.