When Blood and Bones

Cry Out

When Blood and

Bones Cry Out

Journeys through the Soundscape

of Healing and Reconciliation

JOHN PAUL LEDERACH

ANGELA JILL LEDERACH

Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further

Oxford Universitys objective of excellence

in research, scholarship, and education.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Copyright John Paul Lederach and Angela Jill Lederach, 2010. All rights reserved.

Foreword Judy Atkinson 2010

First published by University of Queensland Press,

PO Box 6042, St. Lucia, Queensland 4067, Australia.

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lederach, John Paul.

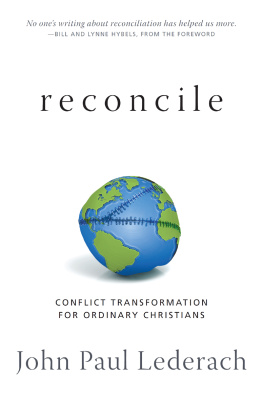

When blood and bones cry out : journeys through the soundscape of healing and reconciliation / John Paul Lederach and Angela Jill Lederach.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-19-983710-6 1. Peace-building.

2. Mediation. 3. Reconciliation. 4. Forgiveness. 5. Conflict

management. I. Lederach, Angela Jill. II. Title. III. Title: Journeys through

the soundscape of healing and reconciliation.

HM1126.L435 2010a

327.172dc22 2011009171

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

For Tom Cauuray, whose life and words inspired our writing, and for his family in the Falui Poets Society who faced the horrors of unfettered violence with the prophetic imagination of memory and hope;

For the family of Efran Arenas and Doris Berrio and the more than four million displaced and disappeared in the Colombian wars;

For Morris Matadi and the thousands of child combatants on the journey to find their way home;

For Kadiatu Koroma and women everywhere who have the courage to give voice to the unspeakable devastation of sexual violence.

Contents

Foreword

When I first read the book Moral Imagination: The art and soul of building peace by John Paul Lederach, I felt the pull towards a kindred spirit, someone who knew something about where I had been and what I was doing in my life and work. John Paul had written in a way that connected with me. I felt he knew the landscape, often a rough, harsh terrain, over which I had been walking, and sometimes a moisture-rich valley of sounds, calling me to places where people desired to sit in the Dadirri circle, listening to and learning from each other.

Later, when he sent me the draft manuscript for When Blood and Bones Cry Out: Journeys through the soundscape of healing and reconciliation, as I read, page by page, slowly, taking time to think, reflect, and reconnect where I had been, I felt and heard that kindred soul speaking to me on another level.

John Paul observed that this writing project with his daughter Angie is one of the most beautiful experiences a father could have. Perhaps even more so is to work with your children on things that matter. When Blood and Bones Cry Out links John Pauls work in many places, but for this book, violence in Colombia links with that of his daughter Angies work with child soldiers in West Africa, coming home from their childhood war zone experiences.

John Paul writes about what he calls a neglected aspect of healing and reconciliation. We too often write about it as a linear process. Of course it is not. And yet as John Paul points out we say healing is not a linear process, and then in the next sentence, as I have done many times, write about the stages and steps of healing.

So, within When Blood and Bones Cry Out, the imagery created, for example, of the Tibetan singing bowl, with the circular process, and the sound, both moving deep into the bowl and upwards in a shared space, provides a visual element, producing for those who have been there the acknowledgement: Yes, I know that space this is how it is! The process is both personal and social healing, as voices mingle, join and resonate with each other.

Within the academy, this creates problems. Personal healing, for them, suggests therapy. Professional skills development is about education, they would perceive, and you cannot mix them. Education, within the western construct, is an intellectual pursuit. Other Indigenous models of education or, as we call it at Gnibi, educaring can provide both and, I would argue, are necessary when working within the field of historic, social trauma and generational community social healing.

I would argue that when working with people who have been through layered experiences of generational trauma, the only ethical approach is to allow both deep personal inner work within the context of social healing, and the development of skills to continue the work with others. In the last month I have seen this possibility while working with my own people in Australia; Aboriginal Australians; and with our brothers and sisters we could call our near neighbours, in Papua New Guinea and in Timor Leste.

In September 2009, I was invited by Peter and Lydia Kailap of Kaugere, a settlement on the edge of Port Moresby, the government centre of Papua New Guinea, to run a five-day workshop with a focus on human rights in relationship to family and community violence. Because there is no school in Kaugere for the children, Peter and Lydia had established the Childrens University of Music and Arts (CUMA), with volunteer workers using music and art to teach children who are eager to learn. Often the only meal the children will receive for the day is at the school. For the five days we were there, the school became an adult learning centre a university. Each day 75 men and women, parents of the 70 children who attend the school, sat together to consider the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of the Child (1959), the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007) in relationship to the violence they live with on a daily basis. Starting with what happens to children when they witness and hence experience violence, the men and the women at first in separate gender groups, and then together worked to develop a community development approach to their needs, which would allow healing to occur across generations. As I think back to those five days I see the metaphor of the bowl taking shape.

In the first round people began to feel safe, so that they could listen and learn together. Once they felt comfortable, not threatened by what they were learning, they went deeper into the bowl, inwards, looking at themselves. And in the circular process of listening and learning together, as their voices grew strong and powerful, the sound rose up, and in the process talking became music, shared between them, and with us, the visitors, a social healing. On the last day, in what they called a

Next page