INTRODUCTION

The crossbow has long enjoyed a popular cachet for dastardly cunning and villainy. It was the subject of two papal bans (in 1096 and in 1139). These incurred a penalty of excommunication, excepting for its use against infidels. Anna Komnene, the Byzantine princess who left an eyewitness account of the First Crusade (109599), concluded that the crossbow was a diabolical mechanism, describing it as verily a devilish invention (Komnene 2009: 282). In England a national love-affair with the longbow, enduring to the present day, has tended to eclipse the military importance of the crossbow in the popular imagination.

A trilogy of crossbow attacks on English kings in the 12th century further feed an unwarranted notion that it is somehow an underhand weapon. While hunting in the New Forest, William II Rufus (r. 10871100) was killed by a crossbow bolt; an assassins blow conferring an association of perfidy to the weapon. His son Henry I (r. 110035) narrowly escaped a bolt shot by his illegitimate daughter Juliana in her failed attempt at both patricide and regicide. In 1199, in France, the English king Richard I (r. 118999) died as a result of gangrene, occasioned by a crossbow bolt in the shoulder at the siege of Chlus Castle. The sniper, famously equipped with a lowly frying-pan as a shield, was a commoner by the name of Peter Basilius. His action, carrying the apparent stain of being unchivalrous, was another blemish on the reputation of the crossbow.

Such a legacy is undeserved. Chivalry was a code of behaviour among nobles of equal status it did not extend to other ranks, nor did it restrict the use of the most capable weapons for the combat at hand. The papal bans were never taken very seriously, intended as they were to curtail the endemic internecine violence among fellow European knights, rather than to ostracize the crossbow itself. Crossbows were ever a high-status hunting arm for the nobility and remained prestigious weapons in general use throughout the medieval period.

Although not new to history, the crossbow had been absent from the European battlefield until its appearance at the end of the 10th century. A few were suspicious of these seemingly new-fangled contraptions, but reactionary voices were quickly drowned out by the louder clamour for military advantage. Prior to the longbows dominance in 14th-century English armies, the crossbow was considered by far the more useful weapon. Moreover, both in continental Europe and in England, the crossbow was the weapon of choice for defending castles and fortified towns from the late 11th to the mid-15th centuries. After that the ubiquity of the crossbow began to fade, increasingly obscured behind a pall of gunpowder.

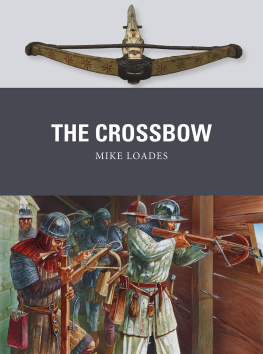

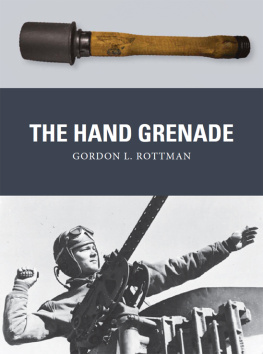

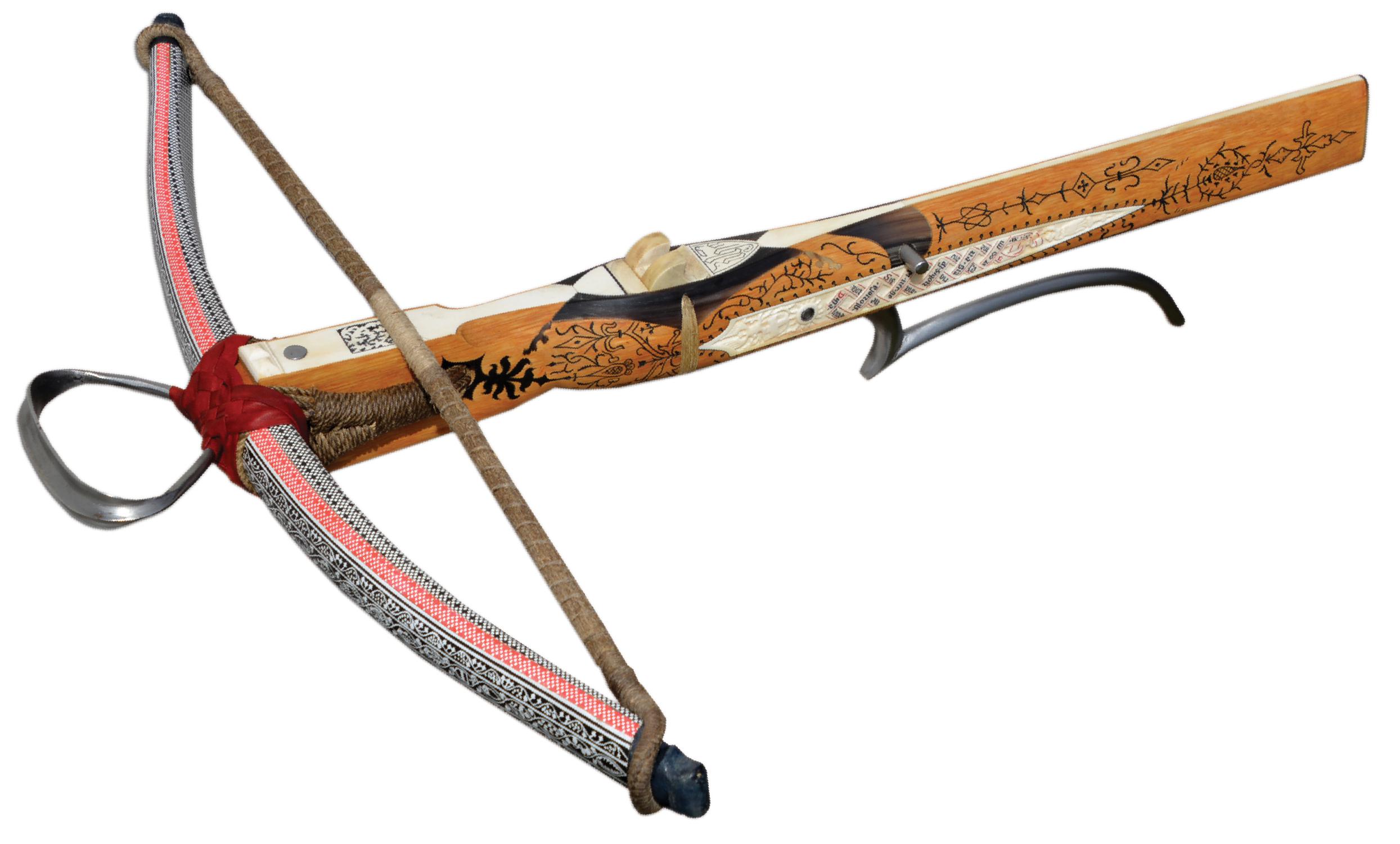

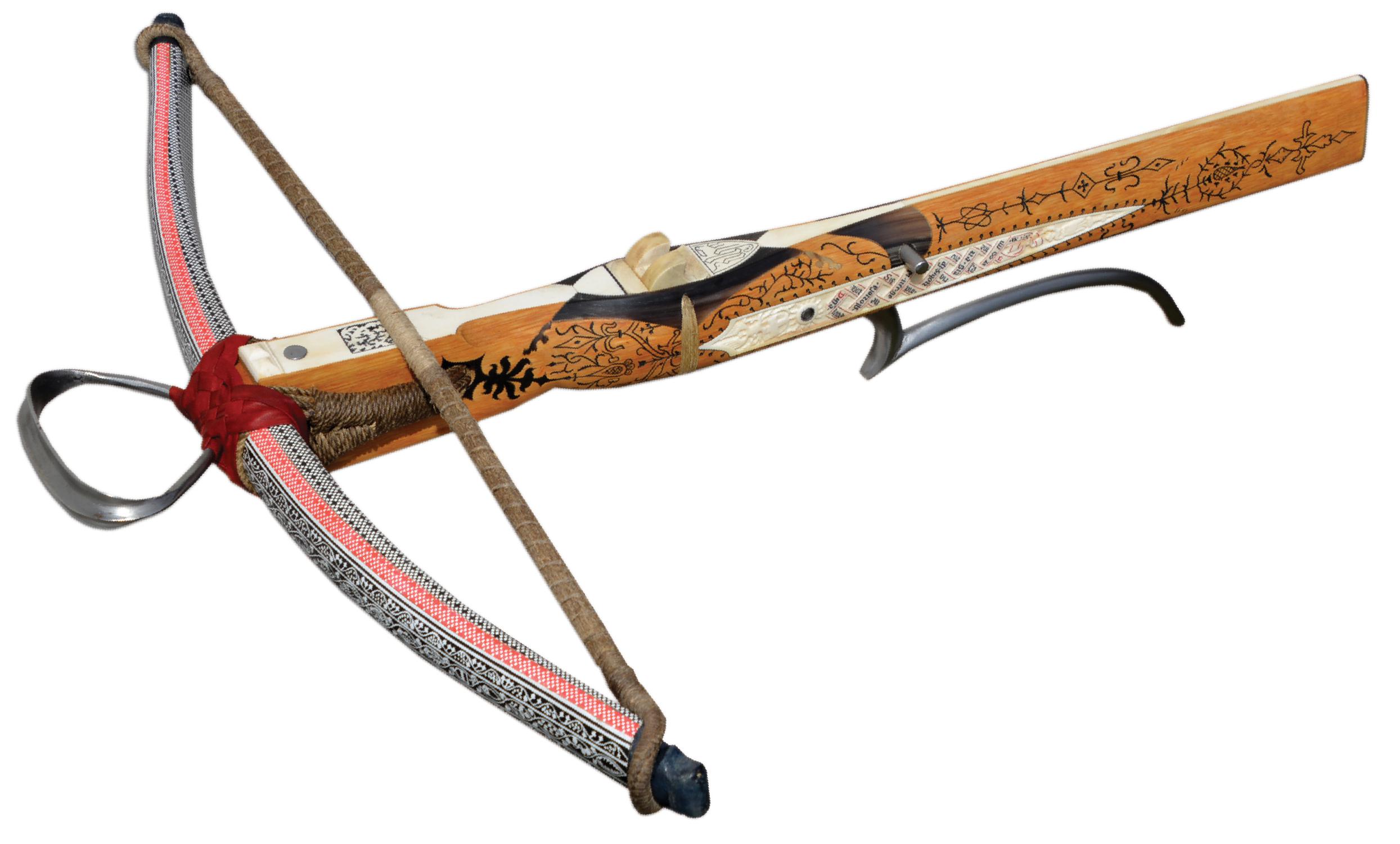

A superb replica, made by Andreas Bichler, of a composite-lathed crossbow belonging to Count Ulrich V of Wrttemberg (141380). The original crossbow is in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. This replica has a hornbeam tiller and the inlaid plates have been made from ibex horn and bone (the bone substitutes for the original ivory). Missing from the museum piece are the string and stirrup, both of which have been incorporated into the working replica. Note the ridge on the stirrup. This was a common feature that allowed for a relatively narrow (and therefore lighter) gauge of metal while maintaining functional rigidity. The double-layer covering of painted birch bark for the lath is also largely missing from the original but two small fragments remain to give a clue to part of the decorative scheme. These fragments reveal a dense pattern of light spots on a black ground. In this masterful rendering of how the original may have appeared, Herr Bichler has given us a glimpse of the vibrant splendour of such high-status crossbows. The verse painted onto the zigzag relief on the cheek piece is a rhyming Latin prayer to the Virgin Mary and also includes the date, 1460, of the bows manufacture. A verse from the Gospel of Luke appears on the opposite side. Other decoration includes the heraldic achievements of the Count and his third wife, Margaret of Savoy, various floral motifs and a cryptic inscription in Hebrew letters on the underside. Despite the elaborate array of painted, inlaid and carved decoration on three of the surfaces, the top surface is relatively unadorned so as not to distract the shooter. (Photograph: Andreas Bichler)

An abiding modern perception is that the crossbow is a weapon of superior technological sophistication and of greater power than the longbow. Though it undoubtedly incorporated some mechanical ingenuity, attributions to its power have been overstated. Very powerful, steel-lathed crossbows did evolve in the 15th century, but during the time of its greatest supremacy on the battlefield roughly from 1100 to 1250 the crossbow packed a more modest punch. Its martial merits hinged not on its power, but on other factors. These included ease of use, comparatively inexpensive ammunition and the ability to hold a bow at full span for a sustained period, waiting to seize the optimal moment for a shot. This latter element was of particular benefit in siege warfare, both for attack and defence, and also at sea. For the hunter, too, the crossbows chief advantage was that it could remain spanned and ready to shoot. It offered stillness and imperceptible movement at the moment of shooting, reducing the risk of startling an animal before the bolt struck home.

This study focuses primarily on the military crossbow of the European Middle Ages and Renaissance, though I have also presented what I consider to be necessary historical and global context with the inclusion of a few crossbows from the Ancient World. In introducing the European crossbow, there is an inevitable English bias to much of the discussion, partly because this undertaking is in English and partly because the crossbow in English armies has been too often neglected in favour of its more fted cousin, the longbow. There is a need to redress that balance.

In a work of this size, it is impossible to also cover the many other variants of the crossbow that occur in places such as Africa, Japan and South-East Asia. Nor is it possible to examine the equally interesting stonebow a variant of the crossbow that featured a double string with a pouch. This propelled either a stone or a clay pellet, used primarily for shooting birds.

Even after they were obsolete on the battlefield, crossbows continued to develop with improved locks, differently shaped stocks and powerful laths. Hunting crossbows and target crossbows remained popular throughout the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. These are the crossbows that mostly populate our national museums. They include glorious specimens, fine works of art; princely arms of the highest order. However, these were not the soldiers weapon. That has left a more ghostly mark, to be glimpsed at only in the dusty pages of inventories and ordnances and with faint glimmers in manuscript art. It is that weapon which is the primary concern in the brief survey that follows.

Terminology

It is necessary at times to distinguish between regular hand-held bows and crossbows. The Close Rolls of Edward II (CCR Ed II) include several references to the term hand-bow in order to make the distinction, as do documents as late as the 17th century. I shall follow that practice here and also use the term regular to indicate hand-bows as opposed to crossbows.

An arbalist is an alternative name for a crossbowman or, sometimes, a crossbow-maker. When spelled arbalest, some dictionaries assign the meaning to be the crossbow itself. The distinction is one of little difference, since both are derived from erratic medieval spelling and the intended meaning is best gauged from context.