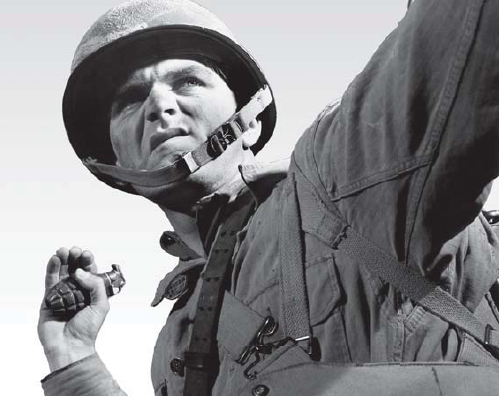

THE HAND GRENADE

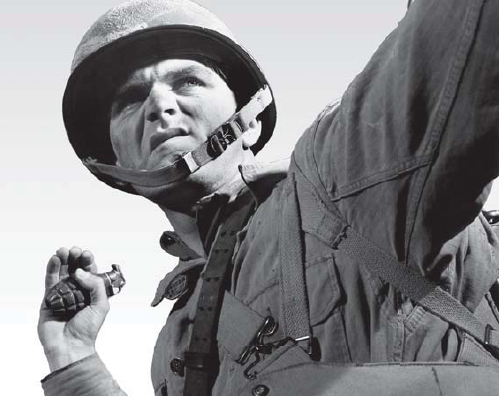

a US infantryman prepares to throw a grenade during training at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, in November 1942. (NARA 196462)

GORDON L. ROTTMAN

Series Editor Martin Pegler

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The hand grenade is essentially a technologically enhanced improvement of what was the first multifunctional, direct- and indirect-fire, offensive weapon employed in warfare the rock. The hand grenade is basically a small missile filled with an HE or chemical agent intended for hand delivery against enemy personnel or material at short ranges. Over time such weapons have been supplemented by special-purpose grenades, which dispense irritant gas, incendiary effects, smoke screening, signaling, or target marking. The most utilitarian grenades are high-explosive/fragmentation (HE/frag or simply frags) casualty-producing antipersonnel weapons. These are referred to as defensive grenades as they are intended to be thrown from behind cover. Another casualty-producing grenade is the blast, concussion, or offensive grenade. These have bodies made of thin, light materials generating little fragmentation. They may be thrown from short ranges using minimal cover. The terms offensive and defensive with respect to grenades were coined by the French during World War I and the nomenclature has subsequently been adopted by many countries. As for practical employment, a soldier will use whatever type of grenade is available. Only defensive and offensive grenades are discussed in detail here, but these weapons role in the development of other types of hand grenade and wider influence on related weapons such as the rifle grenade and the grenade launcher is also covered.

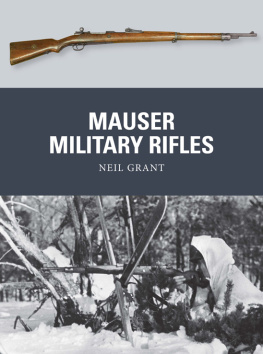

A German Handgranatetrupp (hand-grenade team) rushes across no mans land with each man carrying a pair of hand-grenade bags under his arms, 1917. The rightmost man carries a stick grenade in his hand. They are armed with Mauser 7.92mm Kar 98A carbines rather than the longer Gew 98 rifles carried by other German infantrymen. (Tom Laemlein/Armor Plate Press)

During World War II, Soviet submachine-gunners take up position in a gulley. In the foreground are three RGD-33 stick grenades without the customary add-on fragmentation sleeves, and two RPG-40 AT hand grenades. These relied on blast to buckle the armor and were not of the shaped-charge type. (Courtesy of the Central Museum of the Armed Forces, Moscow via Stavka)

Antipersonnel grenades rely on fragmentation and blast (flash burns, concussion, over-pressure) to inflict casualties. Fragmentation grenades have some form of construction that encourages the body to fragment effectively. The casualty radius can be 520m (5.522yd), but stray fragments can travel over 200m (219yd). Depending on the design and materials, there could be just a few large fragments or thousands. During detonation the cast-iron body actually swells almost to twice its original size. The explosion essentially pulls apart and shreds rather than shatters the grenade. Controlled fragmentation grenades were developed in the 1970s, consisting of thousands of steel ball bearings embedded in plastic bodies. The ball bearings, each 23mm (0.080.12in) in diameter, will travel only a short distance before losing their lethal velocity to reduce the danger to throwers. At close range, though, large numbers of ball bearings will strike targeted troops.

Hand grenades are relatively simple weapons. They must be, owing to the necessity of producing them in huge numbers at low cost while conserving essential materials, and the need to make them easy to use in the heat of combat. They are preferred to be lightweight, reliable, effective in their given role, and foremost safe for the user. This latter requirement means the user has to have confidence in the grenades reliability, the factorys quality control, and the quality of the primer and delay fuse. Among the commonest of soldiers fears regarding grenades are concerns about poor quality control, poor workmanship, or use of inferior materials resulting in delay fuses burning too fast, or causing the sparking primer to blast sparks that would bypass the delay fuse and ignite the sensitive detonator.

There have been many hundreds of grenade models fielded from World War I to the present. Additionally, there are innumerable variants of grenades, not just in functions and effects, but construction means and materials, safety mechanisms, arming methods, identification means, and how they are thrown. There are no unifying similarities between all grenades unless it is the fact that they are hand-thrown. Making assumptions that any two grenades function similarly can be fatal. Grenades require a prescribed manner of delivery to ensure proper employment, maximal effects upon the recipient, and safety of the user. By the nature of their design most hand grenades are readily adaptable as booby traps or early-warning devices. Grenades can be used offensively or defensively. Other than that, there is little in the way of grenade tactics as such. It is a weapon operated by a single combatant, although grenadiers most effectively work in pairs, with the second man providing security. However, during World War I more elaborate grenade tactics evolved employing specially trained and equipped teams to attack and defend trenches.

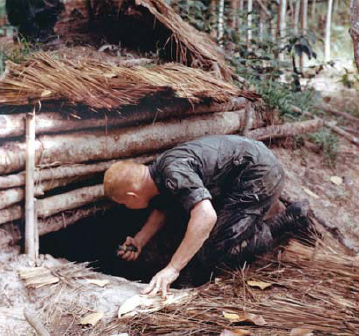

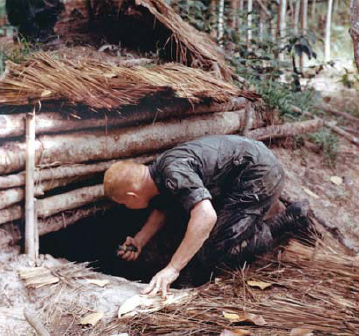

Vietnam, September 1965: a cautious tunnel rat of the US Armys 173rd Airborne Brigade grips an M26 grenade as he examines a Viet Cong bunker. At the slightest sound from within he will lob the grenade, often followed by a second. Smoke and tear-gas grenades were also used to flush out the enemy. (Tom Laemlein/Armor Plate Press)

World War I is considered the golden age of grenades as there were so many successful and less-than-successful types fielded in effort to provide the massive numbers demanded. This included trench-made or expedient grenades of questionable safety. By the wars end the modern grenade had emerged from hard-learned lessons. Since World War I the grenade has been viewed as the infantrymans pocket artillery, the shortest-ranged weapon in a succession of high-explosive/fragmentation-firing weapons ranging progressively upward to rifle grenades, mortars, howitzers, and guns. During the interwar years some improvements were made on fragmentation grenades and a few new special-purpose types were developed. Impact-detonated fuses were looked at during the 1930s, but these proved dangerous to the user. Generally unsuccessful attempts were made to revive them during World War II and again in the 1960s.

By the outbreak of World War II most armies were employing effective grenades and that conflict saw the use of a wide range of grenades, including fragmentation, blast, antitank (AT), incendiary, screening and signaling smoke, various chemical, and others. They were expended in huge numbers in all theaters. For example, the US produced 87,320,000 hand and rifle grenades during World War II. Most countries could not keep pace with the demand. Countries

Next page