First published in Great Britain in 2015 by Osprey Publishing,

PO Box 883, Oxford, OX1 9PL, UK

PO Box 3985, New York, NY 10185-3985, USA

E-mail:

Bloomsbury is a registered trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Osprey Publishing, part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

This electronic edition published in 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

2015 Osprey Publishing Ltd.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library

Print ISBN: 978-1-4728-0657-4

PDF ebook ISBN: 978-1-4728-0658-1

ePub ebook ISBN: 978-1-4728-0659-8

Typeset in Sabon and Univers

Battlescenes by Mark Stacey

Cutaway artwork by Alan Gilliland

Originated by PDQ Media, Bungay, UK

Osprey Publishing supports the Woodland Trust, the UKs leading woodland conservation charity. Between 2014 and 2018 our donations are being spent on their Centenary Woods project in the UK.

www.ospreypublishing.com

The NRA Museums

Since 1935, the NRA Museum collection has become one of the worlds finest museum collections dedicated to firearms. Now housed in three locations, the NRA Museums offer a glimpse into the firearms that built our nation, helped forge our freedom, and captured our imagination. The National Firearms Museum, located at the NRA Headquarters in Fairfax, Virginia, details and examines the nearly 700-year history of firearms with a special emphasis on firearms, freedom, and the American experience. The National Sporting Arms Museum, at the Bass Pro Shops in Springfield, Missouri, explores and exhibits the historical development of hunting arms in America from the earliest explorers to modern day, with a focus on hunting, conservation, and freedom. The Frank Brownell Museum of the Southwest, at the NRA Whittington Center in Raton, NM, is a jewel box museum with 200 guns that tells the history of the region from the earliest Native American inhabitants through early Spanish exploration, the Civil War, and the Old West. For more information on the NRA Museums and hours, visit www.NRAmuseums.com

Acknowledgments

I would like to offer special thanks to my friends Laurie Landau, for access to her splendid Winchester collection, and Dr. Bob Maze, for spending so much time in photographing them. Also to Roy Jinks for allowing me to reproduce images from his seminal Smith and Wesson book, and to the National Rifle Association for access to their collection of firearms images. I am also greatly indebted to Lisa Traynor and Jonathan Ferguson, curators at the Royal Armouries/National Firearms Collection in Leeds, UK, for pictures of some of their extensive cartridge collection. I am also grateful for being able to use some of the fine work done in 2011 by Andrew L. Bresnan and Todd Koster in The Henry Repeating Rifle, which is available online at www.44henryrifle.webs.com/civilwarusage.htm. Special thanks to Michael F. Carrick and Stefan Brinski, who were very helpful in supplying me with information and rare pictures of Winchesters used in French and Russian military service. Finally, thanks as always to my uncomplaining wife Katie for the endless cups of tea and accepting that I spend more time with my keyboard than with her. I have of course tried to ensure all of the facts in this book are accurate, but if there are any errors, the mistake is entirely mine.

Artists note

Readers may care to note that the original paintings from which the battlescenes in this book were prepared are available for private sale. All reproduction copyright whatsoever is retained by the Publishers. All inquiries should be addressed to:

The Publishers regret that they can enter into no correspondence upon this matter.

Editors note

In this book a mixture of metric and US customary measurements is used. For ease of comparison please use the following conversion table:

1 mile = 1.6km

1yd = 0.91m

1ft = 0.30m

1in = 2.54cm/25.4mm

1lb = 0.45kg

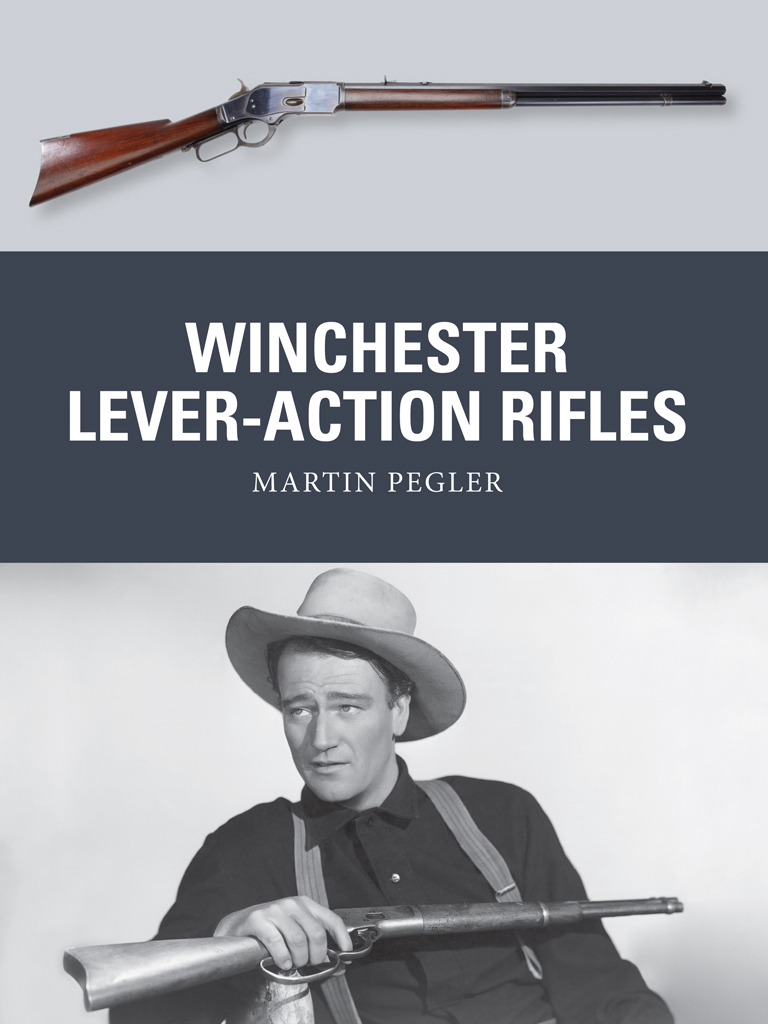

Cover images. Top: A Winchester Model 1873 (NRA Museums, NRAmuseums.com). Bottom: A youthful John Wayne in a studio portrait, carrying one of his favorite screen Winchesters, a Model 1894 Mares Leg with the much-enlarged loading lever ( Corbis).

Title-page image: Taken by N.A. Forsyth in the early 1900s, this portrait entitled Bear Chief and His Hudson Bay Coat depicts a Piegan Blackfoot as he stands, Model 1873 Winchester at his side, before his horse in a campsite, Browning, Montana. Interestingly, he carries a revolver in an improvised, but practical early version of a shoulder holster. (Photo by Transcendental Graphics/Getty Images)

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

From the very inception of the firearm, one of the holy grails for manufacturers was to overcome the constraints imposed by the available technology and create a firearm that had the ability to fire repeatedly. The introduction of the perfected flintlock in the early 18th century did much to improve the reliability and efficient functioning of firearms, but loading and shooting were still tediously slow and much affected by wind and weather, which could blow priming powder from pans or soak the propellant. Gunmakers dreamed of being able to produce guns, both handguns and long-arms, that were able to be charged once and then repeatedly fired. Despite advances in manufacturing techniques, technological progress in the firearms industry was hampered by the only available propellant: gunpowder, a horrible chemical concoction incorporating all of the traits that were most undesirable in a propellant. It was dangerously volatile, usually when it wasnt required to be, but was also hygroscopic (or water absorbing), making it extremely non-volatile, usually at the most inopportune moments. Furthermore, its slow burn rate resulted in relatively low velocities, and it produced a vast cloud of white smoke on firing. Even worse, it left behind a thick, sooty residue that choked gun barrels and touch holes and was highly corrosive if left uncleaned for more than a few hours. But it was all that was available, so for 500 years all firearms makers were forced to work within its confines.

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries a few gunmakers very nearly achieved the impossible by producing revolving-cylinder pistols that relied on flintlock mechanisms. They were large, temperamental, expensive, and generally regarded as no more than novelties, but attempting to do the same with a long-arm was even more problematic. Using the revolving-cylinder system created too much weight and unacceptable loss of propellant gas from the gap between the cylinder and breech. Clearly, some form of breech-loading method was necessary, but this was a problem gunmakers had been wrestling with, mostly without success, for years. Aside from the purely mechanical problems, much of the difficulty lay in the primitive cartridges in use. While paper-wrapped combustible ammunition worked tolerably well in a musket that was loaded and fired fairly quickly afterward, when used in a repeating arm, if the charge was left for any length of time, its hygroscopic properties rendered it useless, requiring the bullet to be removed and the chambers laboriously cleaned out. Even when fired, the gun would need cleaning at frequent intervals to prevent touch holes being blocked, and loading was a tedious process.