Although named Sarah after her mother and a deceased elder sister, Sarah Lockwood Winchester was always called Sallie, nicknamed for her paternal grandmother, Sally Pardee Goodyear, who died just months before Sarah Winchester was born. Sallie stuck, and even late in life Winchester was called Sallie or Aunt Sallie. Nevertheless, for this narrative, she is identified by her formal name.

PREFACE

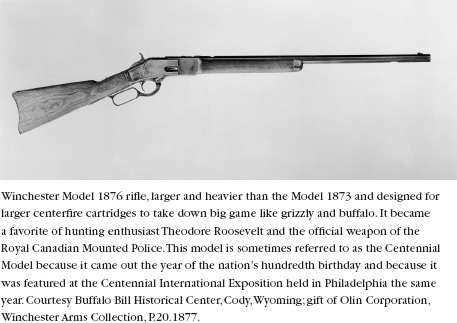

I FIRST SAW A WINCHESTER REPEATER WHEN I WAS TEN YEARS OLD. My brother Mike had been given a 1966 Winchester Centennial .3030 for his eighteenth birthday, and as he took mock aim and cocked the lever, the hallmark of Winchesters, I thought he looked like Chuck Connors in The Rifleman. Mike pointed out the gun's distinctive design featuresthe octagonal barrel, the fine walnut finish, the gleaming gold receiver, and the intricate, eight-cartridge magazine. His enthusiasm did not convince me, though, and I was afraid of the gun. But even as the gift attested to his interest in hunting and his coming of age, it was largely symbolic. The Centennial Model 1966 rifle was a collector's item, a modern replica of the 1866 Yellow Boy, so called because of its brass-colored receiver. The Yellow Boy was the first repeating rifle manufactured under the Winchester name.

The Winchester repeating rifle is legendary, and when my brother received it in the 1960s, it conjured images of cowboys and Indians, bandits and marauders, reinforced by television and Hollywood movies like Jimmy Stewart's Winchester '73 and John Wayne's Rio Bravo. Today, few people are familiar with either those movies or the rifle. Gun collectors and sport hunters may know that the Winchester Repeating Arms Company was sold in the early 1930s, and that products manufactured under that name today are produced by other firms. For most of us, the Winchester is an antiquated icon of the sometimes questionable development and mythology of the American West.

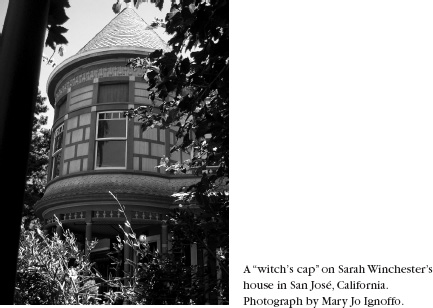

A decade after my brother's birthday, when I lived in the Santa Clara Valley fifty miles south of San Francisco, Mike visited me. By that time he had become a bona fide hunter and sportsman, and had added to his gun collection. He also possessed a substantial store of Winchester trivia. When Mike went to see the valley's hottest tourist trap, the Winchester Mystery House, he gleefully reported back the odd traits attributed there to Sarah Winchester, the one-time owner who had designed the home. He gave chapter and verse of a tour guide's account of Winchester's gun guilt, superstitions, religious practices, and unaccountably weird house. For mypart, I was as skeptical that people paid money to see the Winchester house as I had been about the rifle Mike had received ten years earlier.

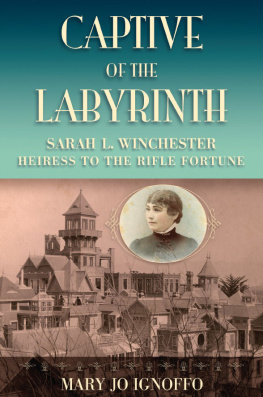

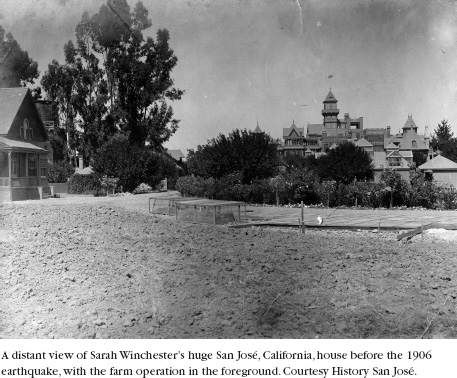

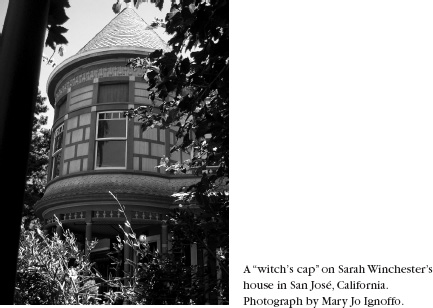

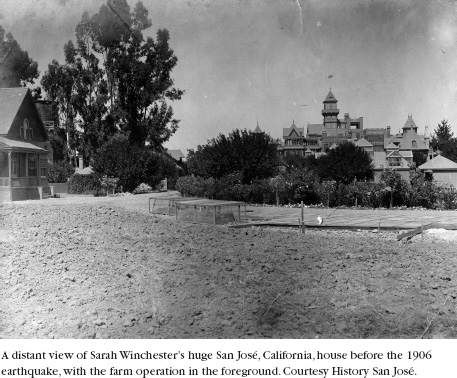

The Winchester house has been a tourist attraction since 1923, the year after the widow's death, when it was reportedly transformed into a haunted house. Over the years the business has subsisted on tourist dollars and during the 1970s and 1980s was spruced up to attract a more discerning traveler. The gangly house is touted by huge red-and-black billboards along California's highways and beyond, luring the curious with a silhouetted house superimposed by a human skull. The signs suggest that visitors may encounter an apparition from another realm. The Winchester Mystery House has emerged as a major California tourist destination, where trade groups and conventioneers are often booked for tours. As the house has become more well known, the person of Sarah Winchester has receded further and further from reality, her real life story obscured by a highly successful advertising campaign.

Almost thirty years after my brother visited, I happened to be conducting research at San Jos's main library one day when the librarian, who knew I often worked on local and California history, suggested that I write a biography of Sarah Winchester. I laughed. Who in their right mind would want to spend years researching and writing about this imbalanced, ghost-obsessed woman, and furthermore, who would read it? Besides, it was often reported that Winchester had left only ghosts behind, no real life records. I am asked for information on her every single week, the librarian insisted, and I have nothing to offer.

He pointed me to a local museum, History San Jos, saying it might have something on her. Sure enough, History San Jos houses a collection from Sarah Winchester's attorney, Samuel Franklin Frank Leib, that contains twenty years' worth of notes, letters, invoices, canceled checks, and magazine subscriptions that paint a picture of a woman far different from her quirky mystery-house persona. The Leib collection led me to one of the same name at Stanford University because Frank Leib had also been counsel to Jane Stanford and had served on Stanford's board of trustees during its first twenty-five years. Stanford's archives also hold correspondence between Winchester and Leib. Both collections surprised me with her handwritten directives and legal questions there. I was intrigued by little things in the collections such as a Christmas list, receipts for a succession of automobiles, subscriptions to Architectural Record, and canceled bank drafts. Here was the stuff of a lifea business life at the very least. Was there more?

Another collection at History San Jos offered me an even more personal side to this unusual woman. A Winchester employee, John Hansen, and his wife, Nellie Zarconi Hansen, lived and worked for almosttwenty-five years at Winchester's San Jos ranch, where they raised two sons, Carl and Ted. In the 1970s, their descendants donated photographs, letters, and scrapbooks to the museum. More recently, Carl's son, Richard Hansen, gave the museum a collection of daybooks, one for each year from 1907 to 1922, in which John Hansen had made notes about operations at the ranch and the comings and goings of Mrs. W. The daybooks and Leib's letters document which of the five Winchester-owned houses Sarah Winchester happened to be visiting on a particular day or week or decade. This group of records sheds considerable light on Winchester's day-to-day life.