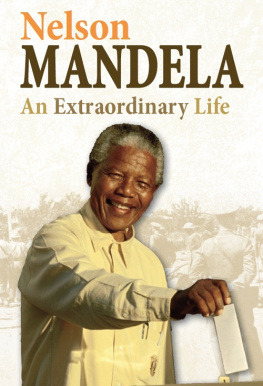

Lodge - Mandela

Here you can read online Lodge - Mandela full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2006, publisher: Oxford University Press USA - OSO, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Mandela

- Author:

- Publisher:Oxford University Press USA - OSO

- Genre:

- Year:2006

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Mandela: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Mandela" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Lodge: author's other books

Who wrote Mandela? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Mandela — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Mandela" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

CHILDHOOD AND UPBRINGING

In the world into which Nelson Mandela was born in 1918, children were best seen, not heard. We were meant to learn through imitation and emulation, not through asking questions, Mandela tells us in his autobiography. Despite his early upbringing in a village community composed mainly of women and children, from infancy his social relationships were regulated by strict conventions and precise rules of etiquette. In this vein, much of the emphasis in most accounts of Nelson Mandelas childhood has fallen on what he was told and what he presumably learned rather than on what he felt or perceived.

Lineage enjoys pride of place in Mandelas testimonies about his childhood. When Meer wrote her authorised biography in 1988, Mandela himself, then still in prison, compiled a family tree and supportive notes for a genealogy passing through ten generations. This indicated his line of descent in the Thembu chieftaincy as a member of its left-hand house of King Ngubencuka, who presided over a united Thembu community in the 1830s. The Thembu were one of twelve isiXhosa-speaking chieftaincies that inhabited the Transkei, the largest of South Africas African peasant reserves situated on South Africas eastern seaboard. The Thembu lefthand house, descendants of Ngubencukas third wife, by convention served as counsellors or advisers to the royal household, the sons of Ngubencukas Great House. In this capacity, Mandela suggests, his father Henry Gadla Mpakhanyiswa can be thought of as the Thembu paramounts prime minister, though more prosaically he was accorded the post of village headman at Mvezo near Umtata by the administration of the Transkeien territories, a secular authority of white magistrates and other officials. Henry Gadla and his family belonged to the Madiba clan, named after an eighteenth-century Thembu chief: Mandela today prefers to be called Madiba by his friends and associates.

Much is made of Mandelas aristocratic or even princely status in the various narratives of his life. In these Mandelas genealogy is an important source of his charismatic power. Since he was a small boy in the Transkei, Mandela was treated as someone special, notes Richard Stengel, Mandelas collaborator on his autobiography. His political confidence was substantially derived from the security and simplicity of his rural upbringing. Mandela himself maintains that much of his childhood was a form of apprenticeship shaped by knowledge of his destiny, in which he would ascend to office as the key counsellor to the Tembu chiefdom. Popular accounts of his birth and upbringing, including those prepared by the African National Congress (ANC) in the early 1960s, accentuate his social status and his royal connections.

Nelson Mandelas father, Henry Gadla, was a relatively wealthy man in 1918, rich enough to maintain four wives and thirteen children. Mandela, incidentally, was the most junior of Gadlas four sons and he has never explained why he was cast in the role of future counsellor to the Thembu paramount. His mother, Nonqaphi Nosekeni, may have been his fathers favourite wife; such considerations could influence inherited precedence among sons.

In the 1920s, the Transkei could still support a peasant economy although most young men migrated elsewhere to work: Mandela remembers that in his mothers household milk was always plentiful.

According to his surviving relatives, Mandelas learning began well before he started attending mission school. Apparently, as a solemn boy among the many descendants of the great Xhosa chief, Ngubengcuka he would listen by the fireside to his great uncles accounts of the Xhosa frontier wars with the British a gentle signal in his narrative of an opening of an intellectual and emotional distance between himself and the world of his childhood.

Standard British textbooks were to play their role in shaping Mandela intellectually through primary school and later through his

Relationships between black and white staff were at least formally collegial, as is indicated in contemporary school photographs, and Mandela was deeply impressed by one incident in which the housemaster, Reverend Seth Mokitimi, in front of the boys stood up to the authority of the principal, demonstrating that a black man did not have to defer automatically to a white, however senior he was.

At Clarkebury and Healdtown, Mandela may have consciously resisted becoming a black Englishman

School also augmented his respect for order, discipline, structure, and authority: as a prefect at Healdtown, classmates remember an exemplary (if uncharacteristically self-righteous) occasion when Mandela leapt onto the dining room table and exhorted his fellow students to take more responsibility for their behaviour.

From Mandelas recollections of Xhosa oral traditions recounted during his childhood and from his own membership of a patrician dynasty, South African nationalist historians readily identify connections among pre-colonial institutions, primary resistance to colonial rule, and the ANCs struggle for modern rights. Both in the 1960s and more recently, the efforts of the ANCs leadership to secure the support of traditional rural notables have supplied a strategic motivation to highlight such connections. Mandela himself was to suggest in his trial speeches that the seeds of revolutionary democracy were present in the consensual procedures that he observed at Jongintabas court. Mandela claims that his own notions of leadership were substantially shaped by what he observed as a child at the Great Place.

But the world in which Mandela grew up was complicated by the presence of competing institutional sources of power, culture, and moral authority, which, moreover in their local contexts, influenced each other. Thembuland had been subjected to a colonial administration since the 1880s and, alongside a bureaucratic administration incorporating chiefs and headmen, an elected system of representation was introduced in stages from 1895 in which a mission-educated

By the time of Mandelas schooling, a printed Xhosa literature existed, initially a product of publishing by the Glasgow Missionary Society from 1821. During Mandelas youth, Samuel Mqhayi, to whom he had listened at Healdtown, was the most influential Xhosa writer. Mqhayis writing was itself an example of the cultural synthesis between English and Xhosa represented by the literary standardisation of Xhosa in its adaptation of the traditional genre of isibongi (praise poetry) to the formal conventions of Victorian English verse.

The Methodist church itself, in the Transkei, was substantially African, its members, like Mandela himself, moving backwards and forwards between what they later described as British and ancestral frameworks of cultural reference. The social order at Jongintabas Great Place was syncretic. Before dispatching his ward to the missionaries boarding school, the Regent arranged for his passage into manhood through the customary procedures of circumcision and initiation. Mandelas narrative concerning this experience is extremely detailed: in his autobiography it is the most vivid and introspective recollection that he has of his childhood. Mandela recorded his autobiography, partly through oral testimony, in the 1990s. By this time his initiation had become a key episode in his life history, an extended narrative into which he condensed important social and cultural commentary.references to wider explorations of change and they deserve careful reading. What Mandelas story records is not a tradition inherited pristine and intact, but rather a set of rituals which by the early 1930s were already losing some of their force and meaning.

The lodge was constituted to accompany Justice, Jongintabas son, through the ceremony. It assembled itself near the traditional place for the circumcision of Thembu kings. Custom required the performance before the ceremony of an act of valour: the cohort settled for stealing, butchering, and roasting an elderly pig. Mandela remembers a moment of shame for having been disabled, however briefly, by the pain of the crude surgery of the circumcision itself. Each initiate received a new name; Mandelas was Dalibunga which can be translated as maker of parliaments. The initiates were permitted to forego the tradition of sleeping with a woman at the end of their seclusion and Mandela violated customary protocol by returning to the burning lodge to mourn for my own youth. For him, the mood of triumph and achievement that should have marked the occasion had in any case been disrupted by the words of Chief Meligqili, summoned to deliver the expected congratulatory homily. Instead Meligqili had told the initiates that the ritual that promises them manhood was an empty illusory promise:

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Mandela»

Look at similar books to Mandela. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Mandela and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.