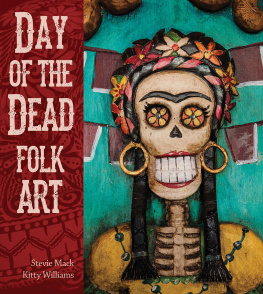

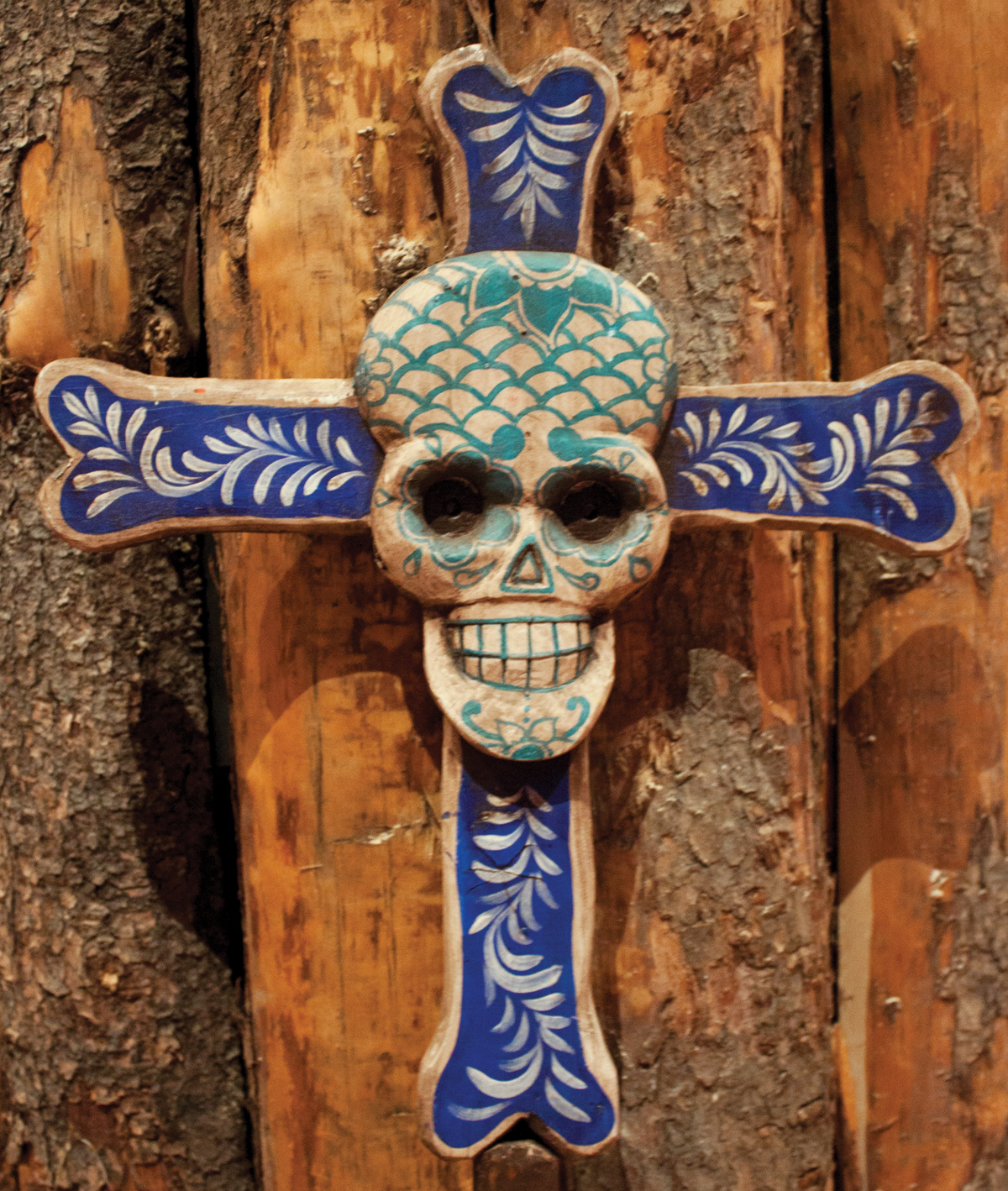

Day of the Dead Folk Art

Stevie Mack

Kitty Williams

Day of the Dead Folk Art

Digital Edition 1.0

Text 2015 Stevie Mack and Kitty Williams

Photographs 2015 Stevie Mack and Kitty Williams

Front cover art by Gennaro Garcia, Phoenix, Arizona

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except brief portions quoted for purpose of review.

Gibbs Smith

P.O. Box 667

Layton, Utah 84041

Orders: 1.800.835.4993

www.gibbs-smith.com

ISBN: 978-1-4236-3444-7

To Mike, Chelsea, Scott, and Aubrey, with much love. SM

To my parents, Pat and Ed, who have been there through it all. KW

Acknowledgments

Many people have contributed generously to this book, sharing their advice, support, and enthusiasm. First and foremost, we are grateful to the many artisans who created the fabulous folk art featured in this title. This book is a celebration of their vision and talent.

We would like to thank Gibbs Smith for giving us the opportunity to work with his highly professional staff on this project. Our editor, Bob Cooper, gave us incredible guidance and support from the beginning to the end. His enthusiasm for the topic was encouraging throughout the process.

We are very grateful to the owners of two folk art galleries in California who welcomed us to their establishments, and gave us access and permission to photograph their collections. These galleries represent many of the finest folk artists exhibiting today. Rocky Behr and her staff at the renowned Folk Tree in Pasadena gave us a warm welcome and were available to assist in every way possible. Elexia de la Parra from Casa Artelexia in San Diego provided us with a comfortable space to photograph and offered us access to their collection. Her generosity was critical to the success of this project.

A heartfelt thank you is due to Mike Grassinger, whose steadfast support was invaluable. He offered assistance whenever and wherever it was needed, providing transportation, sustenance, lighting and set design, and general schlepping. His patience and support made this publication possible.

A special thanks to friends and colleagues Nancy Walkup, Bill Yarborough, Colistia and Tom Sawyer, Betty Rowe, and Pat Manion, who gave us advice, encouragement, and permission to photograph their private collections. We would like to extend our deep appreciation to Barbara Cavett at CRIZMAC, who was willing to take the reins and run the store and care for our customers while we traveled and photographed.

And finally, we are grateful to Mary Jane McKitis for her vision and tenacity in making this project a reality.

Introduction

The art of the craftsman is a bond between the peoples of the world.

Florence Dibell Bartlett

Founder of the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico

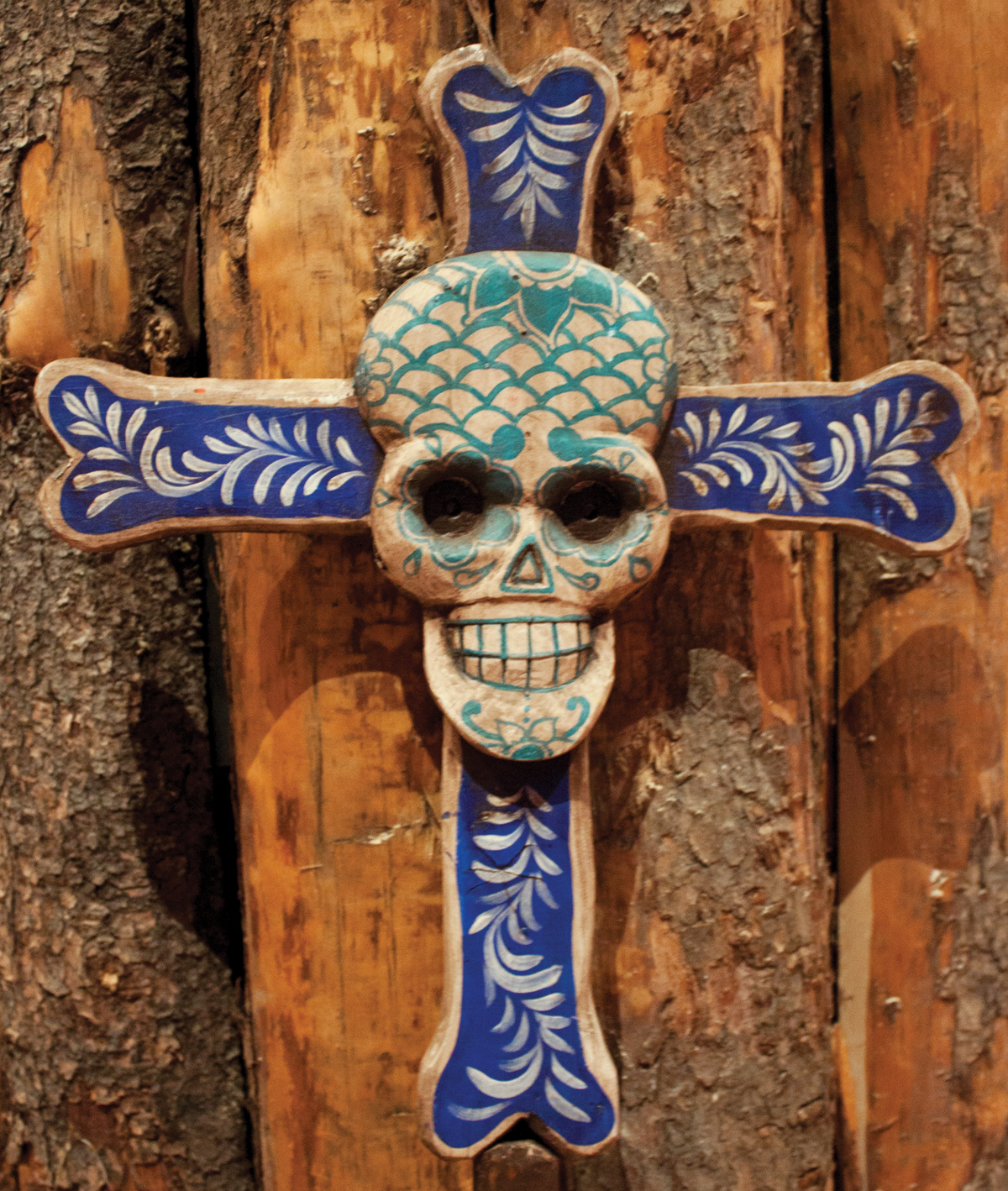

A long row of wooden skeletons hangs in a shop window, their lanky bones dancing a clickety-clacking jig in the breeze. From a building overlooking the street, a tall, elegant skeleton in a wide-brimmed hat and feather boa waves to passers-by. Grinning skulls, ranging in size from miniature to larger-than-life, seem to be everywherein the markets; on home altars, or ofrendas ; in shops, hotels, and other businesses; and adorning the graves in the cemeteries. Made of nearly every material imaginable, from sugar and papier-mch to amaranth seed, the skulls whimsical expressions and colorful features create a cheerful rather than morbid mood. Although the preponderance of death imagery may be initially disconcerting to those unfamiliar with the Day of the Dead celebration, the skulls and skeletons are intended to be humorous and are created in recognition of the fleeting nature of life. The holiday has inspired a wide variety of art, in keeping with Mexicos rich folk art tradition.

In the 1500s, when Hernn Corts arrived in present-day Mexico, he described the Aztec capital and its market of textiles, feathers, gourds, and precious metals. Because the Aztecs had conquered many of the neighboring tribes, they were able to adopt many of their skills and techniques for making a range of crafts.

Following the Spanish conquest, some indigenous crafts were lost, but others emerged, and often represented a synthesis or mingling of the two cultures. The Catholic Church also provided a rich source of imagery. In this way, the Spanish conquest changed the artistic, as well as the spiritual, traditions of the people of Latin America.

Crafts remain an essential part of life in Mexico. While the country has given the world such well-known and well-respected fine artists as Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, the art and cultural traditions of many indigenous groups continue to thrive. The folk art they produce identifies them as a people, and serves as a source of pride for their communities. From raw materials as varied as the terrain and geography, a great deal of wonderful art is produced by artists who sell their works from home studios or at local markets and small shops. In the past, most indigenous artists were known only by members of their own communities and a few outside collectors, and consequently did not enjoy widespread recognition.

An early collector of world folk art and the founder of the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Florence Dibell Bartlett believed that an appreciation of folk art was one path to international understanding. Certainly, the traditional arts and crafts produced by native peoples around the world reflect many aspects of their cultures, and thus offer outsiders a window into the values and traditions of the people.

Regardless of where it is produced or by whom, most traditional art forms share a number of characteristics. Folk art is generally produced using simple technology from local materials that are readily available. The traditions are passed down from generation to generation, and as a result the art often expresses village or cultural identity through themes that are derived from the daily lives of the artists. For many artisans in Mexico and elsewhere, their art is the means by which they provide economic support for their families, and it enables them to continue to live traditional lifestyles. Another common characteristic of folk art, which is particularly evident in the Day of the Dead celebration, is that it frequently originated for functional or ceremonial purposes.

Woodcarver Agustn Cruz Tinoco, from San Agustn de las Juntas, Oaxaca, Mexico, uses a machete and a knife to carve his figures by hand.

In many families the women use acrylic paint to decorate the woodcarvings created by a spouse or other family member.