Contents

Page List

Guide

The Doctor to the Dead

The Doctor to the Dead

Grotesque Legends & Folk Tales of Old Charleston

John Bennett

Introduction by

Julia Eichelberger

1943, 1946 by John Bennett

1995 by the University of South Carolina

Introduction 2020 by the University of South Carolina

First published in 1946 by Rinehart & Company

Paperback editions published in Columbia, South Carolina, by the University of South Carolina Press, 1995, 2020

www.uscpress.com

29 28 27 26 24 23 22 21 20

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

can be found at http://catalog.loc.gov/.

ISBN 978-1-64336-137-6 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-64336-138-3 (ebook)

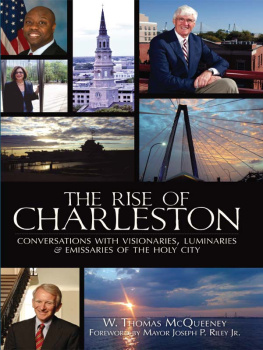

Front cover art: St. Philips Church, Charleston, S.C., ca. 1900,

Library of Congress. Design by Adam B. Bohannon

An old city without legends is like a cow without a cud

DuBose Heyward

Contents

Introduction

Remembering and Rewriting Gullah Narratives

Mary Simmons. Walter Mayrant. Ceasar Grant. Emmy Seabrook. Epsie Meggett. Araminta Tucker. Sarah Rutledge. Eliza Burns. Jerido Mikel. Alec Williams. Hardy Pudigon. Nathan Dobson. Archie Simms. Joe Powell. Isaac Ramsay. Jackson Tinker. John Smalls. These are the names of some of the African-descended people who lived in nineteenth-century Charleston, South Carolina, and shared tales of ghosts, conjuring, superhuman feats, and supernatural powers with a white fiction writer and illustrator named John Bennett. An Ohio native who had moved to Charleston in 1898 and married into a prominent Charleston family, Bennett was intrigued by the Gullah language that most Black Charlestonians spoke. Curious to learn more, he began filling notebooks with material gleaned from the few published sources that were available and from conversations with Gullah speakers.

The tales in The Doctor to the Dead attest to the creativity and cultural resilience of African-descended people in Charleston and the surrounding Lowcountry. However, readers interested in the subjectivities of Black Charlestonians will be disappointed if they turn to this book for unmediated versions of their narratives. When Bennett did his research, no sound-recording equipment was available, nor did he preserve anything like field notes in the twenty-nine linear feet of materials in his papers in the South Carolina Historical Society. What we have, instead, are Bennetts own retellings and reworkings of stories he had been told.

Almost all the tales in the collection are now in literary, formal English. As Bennett noted in his Introductory Comment that precedes the stories in this volume, he needed to translate the well-nigh incomprehensible dialect spoken by primitive black folk of the South Carolina coast lest the tales highly dramatic quality be lost or obscured in the grotesquery of the original dialect (p. xxx). Since the early 1900s, he had been trying to establish [his] reputation as an authority on the language, beliefs, and culture of African Americans in the Lowcountry. Believing his readers needed to be guided through this strange material, he arranged the tales in a graduated scale from sheer fantasy, [Madame Margot], to simple grotesquery and fable-like simplicity in those which approach the finished folk-story in set form. Bennett is not, ostensibly, the narrator of the last three tales, which are presented as told by Ceasar Grant, Sarah Rutledge and Epsie Megget, and Walter Mayrant. Even these narratives, replete with Gullah words and nonstandard dialect spellings, are, according to Bennett, in a modified Gullah comprehensible, it is hoped, to the general reader (p. xxx).

Do Bennetts rewordings and reworkings of Gullah narratives make these tales inauthentic? The question is complicated. When Drums and Shadows (1940) quoted the words of residents of the Sea Islands, parts of interviews were cut, and the questions the white interviewers posed reflected the answers they hoped to find.

Like all narratives, Bennetts stories hold contingent meanings, reflecting the lives of the original tellers and the meanings these stories held for them, but also meanings he found there. As James Clifford wrote, Even the best ethnographic textsserious, true fictionsare systems, or economies, of truth. Power and history work through them, in ways their authors cannot fully control. When reading Doctor to the Dead, then, we should consider the powers and histories working through both sets of texts: the narratives Bennett heard and the tales he wrote for this book.

When Bennetts research began, many aspects of African American life were unexplored or deliberately disregarded by whites; publications on Gullah culture, and on African Americans more broadly, were not extensive. but many white Charlestonians interpreted them as evidence of the plantation tradition that glorified the antebellum South, or at least the Lowcountry. In this imagined Southern past, plantation labor camps became benevolent pastoral communities where the enslaved were grateful for their enslavers generous paternalism.

Few professional writers took interest in Gullah culture at the turn of the twentieth century. No writer had attempted a collection of Gullah tales centered in Charleston or published on the Gullah language before Bennetts 1908 article, Gullah: A Negro Patois. Bennett also used his research on Gullah language and lore in a 1906 novel, The Treasure of Peyre Gaillard. The novel includes a version of a tale published here, The Apothecary and the Mermaid. One plot twist hinges on Gullah: a treasure is unearthed when the hero translates sentences, previously thought to be gibberish, that direct him to the burial spot. Bennetts novel was well received, and he eagerly continued researching Gullah folkways, often talking with African Americans who worked for his family or in the households of friends.

One story Mary Simmons told him in 1907 became The Measure of Grief in this collection. He sent the narrative to his mother the day he heard it, explaining, I went straight to the machine and wrote, in Marys periods, as closely as I could turning the dialect into English: this is the story: I cant resist sending it for you all to see, it is so genuinely good! After writing the story, he added, If that is not a genuinely good folk-story I do not know one when I see it. Later that summer he heard stories from Walter Mayrant about a man who had the gift of strength (one source for Rolling Rio) and about people flying away from slavery on the wings of rest (Bennetts original title for All Gods Chillen Had Wings). In a letter describing these tales, Bennett wrote, Maybe somebody, some day, will appreciate these really uncommon things. He was disappointed that Harpers had not yet responded to his submission of The Measure of Grief.

Nothing, however, prepared Bennett for white Charlestonians 1908 response to his lecture for the Federation of Womens Clubs. He presented several tales hed written up, including Madame Margot, about a mixed-race dressmaker who was the mistress of a wealthy white man with whom she had a daughter. In another (here called The Black Constable), a conjurer worked a charm using a young womans chemise. Bennett did not realize he was crossing a line by using the word chemise and mentioning race mixing in front of women. He discovered his mistake the next day, when the newspaper castigated him for his subject matter: richnot to say reekingwith the distorted and horrible and forbidden fancies of the savage nature still latent in the negro. Letters to the editor agreed that Bennett had insulted his audience. If these legends are so coarse and vulgar, and if in no other form can they be learned, by all means let us be ignorant. It is not necessary to go to the sewer for information, wrote one attendee, signed A Charleston Lady. Another added, If we are compelled to live in the midst of a semi-barbarous race, let us forget it as much as possible, except inasmuch as we can uplift it through Christian charity and by moral example.