SLAVE CABINS

With the physical and emotional tumult that accompanied slave life on many plantations, it is easy to recognize why tormented spirits might crystallize around these properties.

Plantation slaves were allotted particular areas for their living quartersslaves who worked in the plantation house or in the barns enjoyed better living conditions than the larger majority of field hands. On some plantations, the owners provided all the necessities for their slaves, from housing to food and clothing. On others, the slaves built their own cabins. These tended to be reminiscent of houses in the Caribbean islands or West Africa, with thatched roofs and close proximity to the water. Some were adorned with haint blue paint on the door or inside walls near the beds for protection from wandering spirits or haints. As slave populations swelled in the eighteenth century, living conditions became cramped with sometimes as many as ten people sharing a hut.

Slaves had little furniture except for what they found time to createtheir beds were usually hay or cotton. The long hours they had to work meant that they had little free time for making things to improve their living conditions. Because some slaves were without the basic necessities of pots and pans, they used a hollowed out pumpkin shell, called a calabash, to cook their food.

The photographs on the following pages reveal the variety of slave cabins across the Lowcountry where slaves lived and where some of their ghosts may still linger.

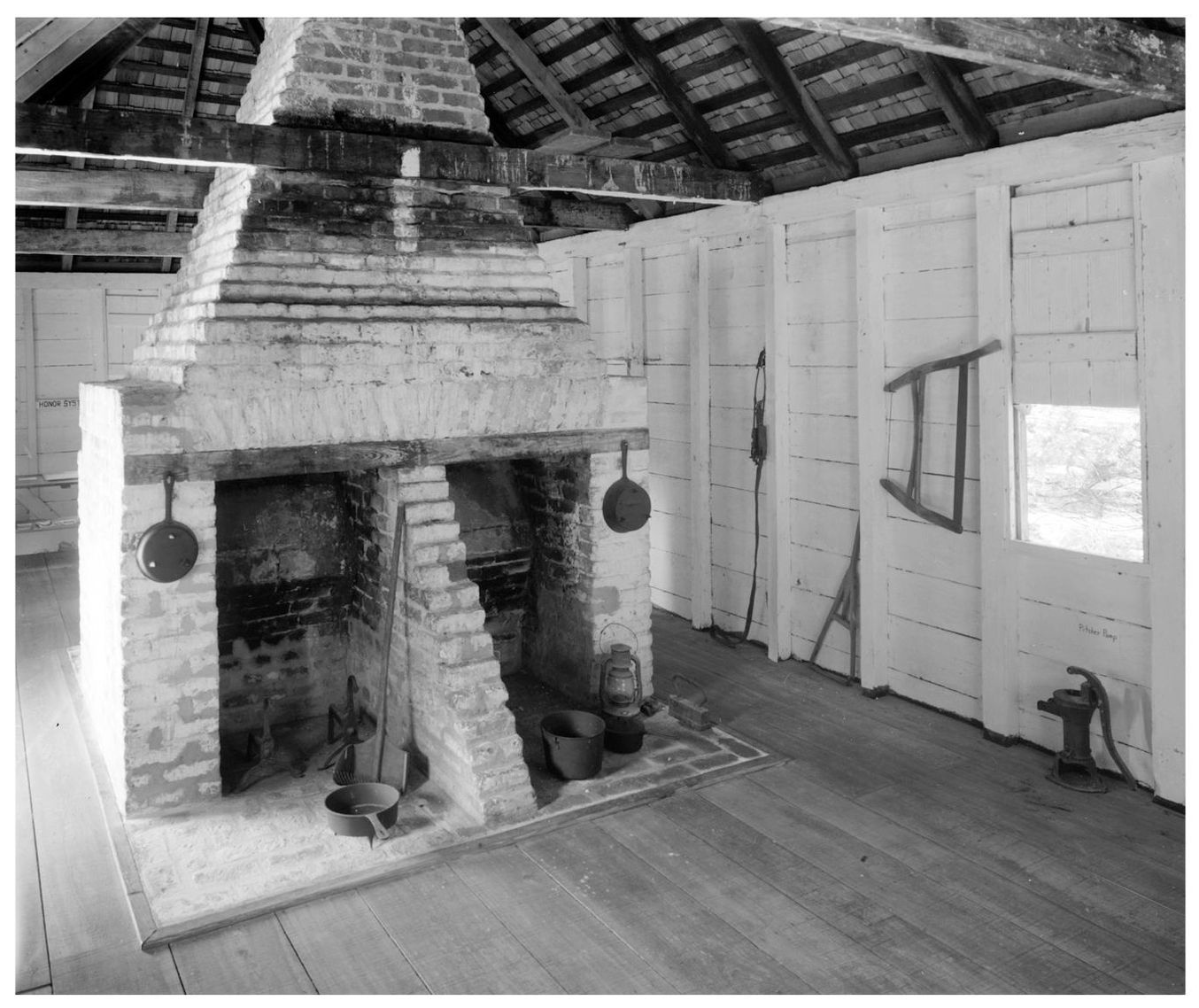

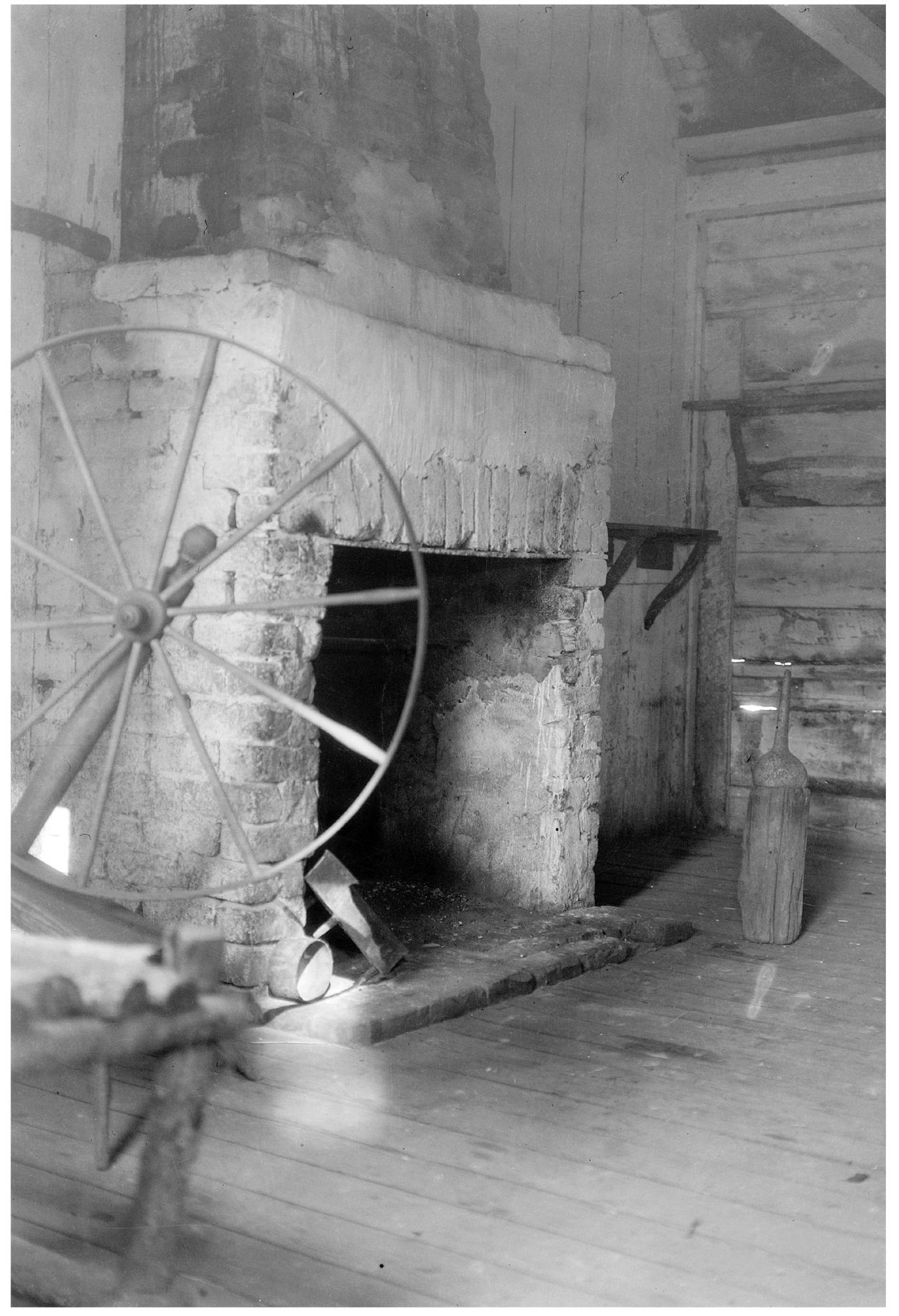

The thatched-roof interior and double fireplace of this slave cabin shows how two or more families lived on the North Santee River at Hopsewee Plantation near Georgetown, South Carolina.

This Stone Creek cabin on Sunnyside Plantation on Edisto Island, South Carolina, shows just how cramped living conditions could be.

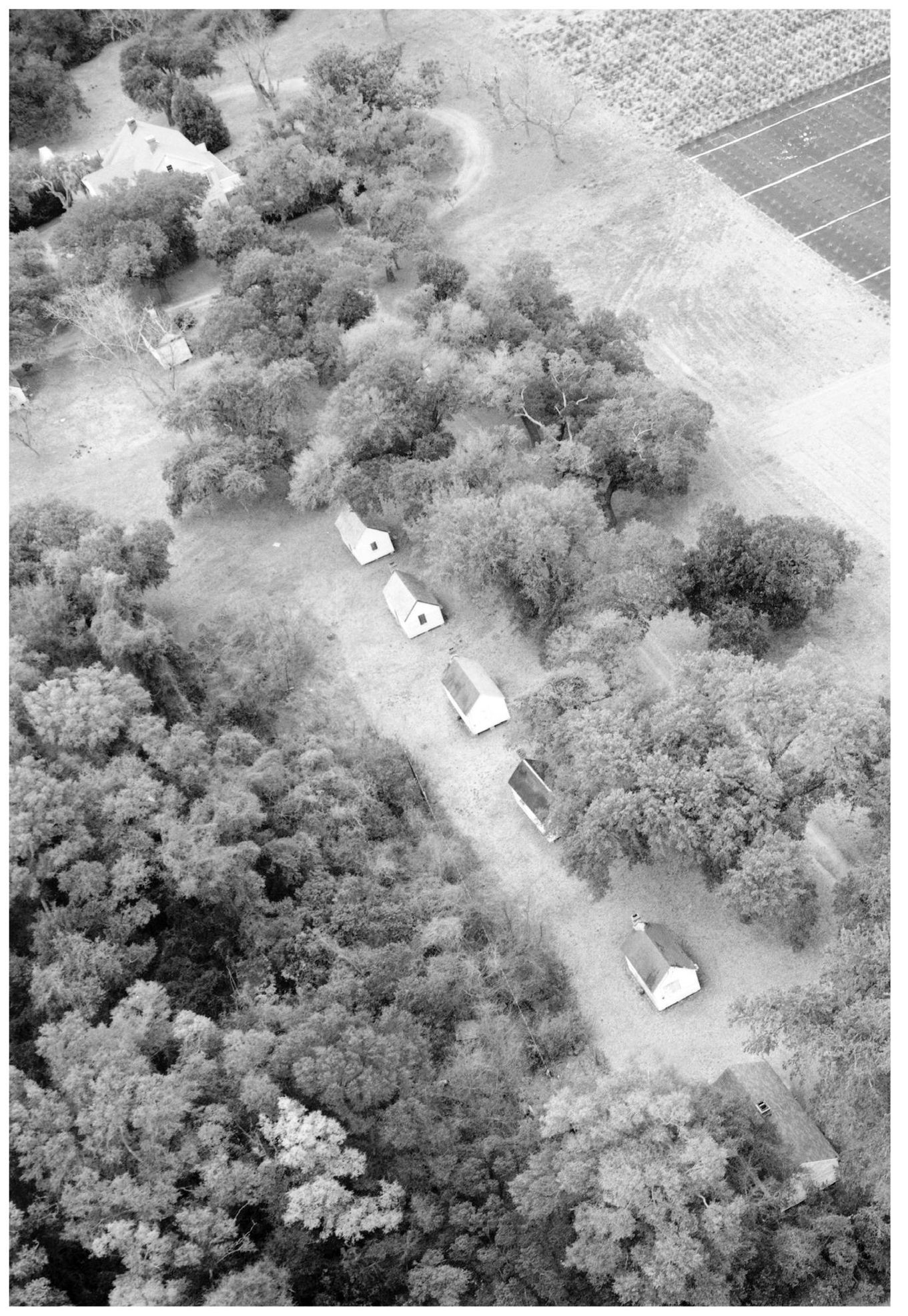

According to an 1860 census, 74 slaves lived in 26 cabins at McLeod Plantation on James Island, South Carolina. Nine 20-foot by 12-foot cabins remain today and were rented out to local families by William McLeod until he died in 1990 at 105.

The Slave Street cabins at Boone Hall in Mt. Pleasant, South Carolina, were made from kilns at the plantation brickyard on Wampancheone Creek. They are believed to be the only brick slave cabins remaining in the United States.

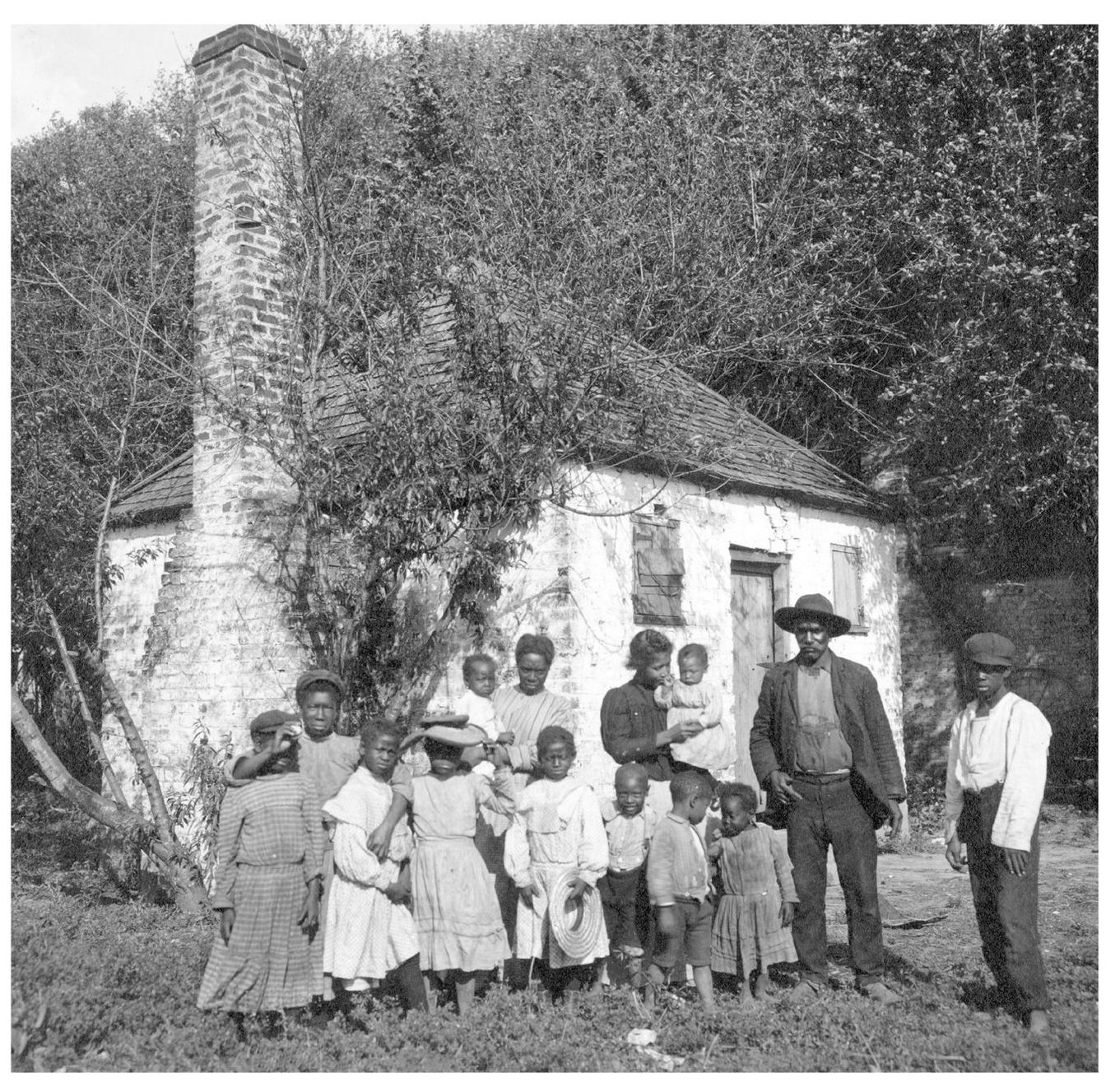

The Whole family posed outside this former slave cabin at the Hermitage Plantation near Savannah, c . 1907.

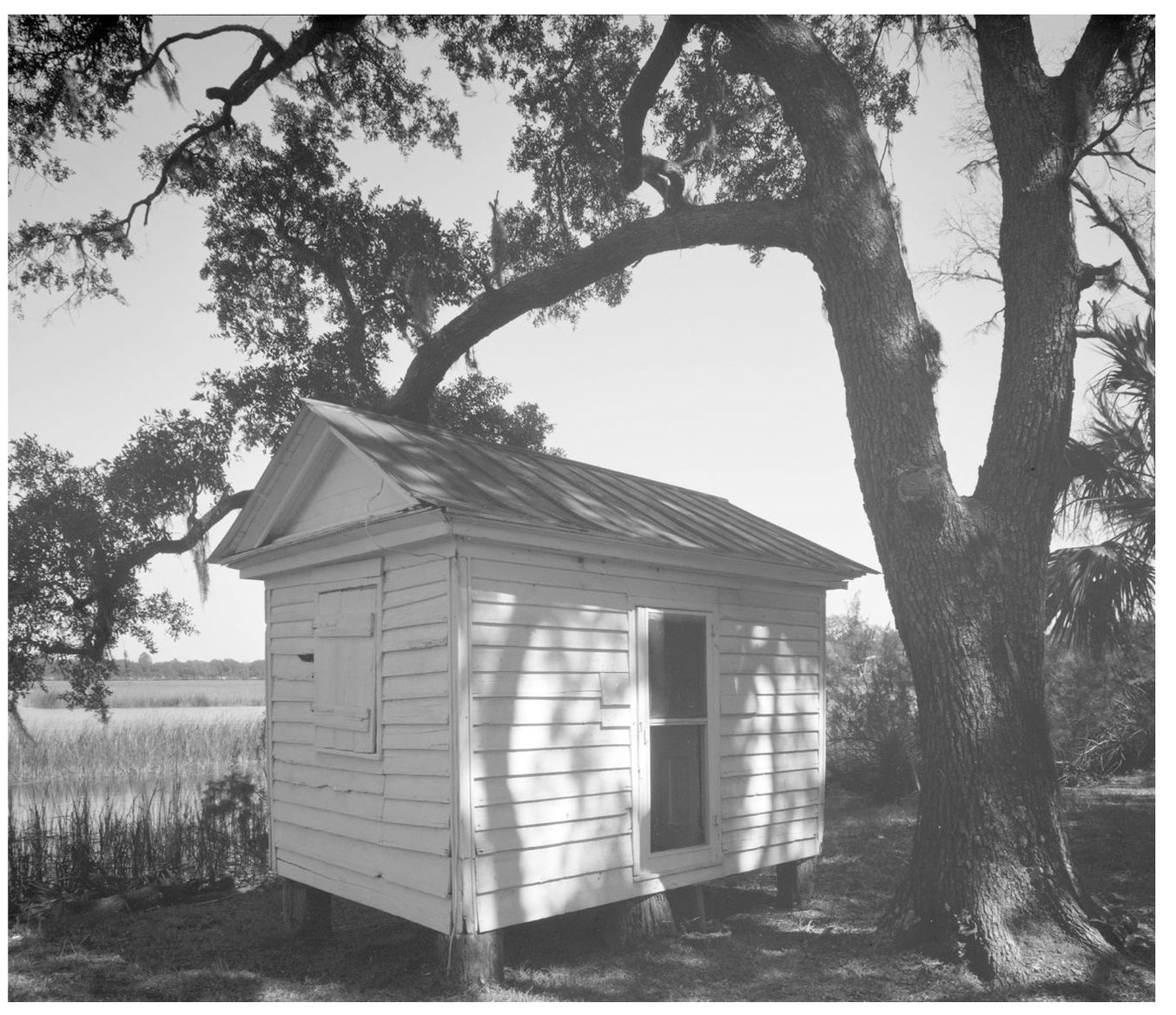

This marsh-front dwelling was occupied by slaves whose main production was rice. It is the only one that remains on the Isle of Hope near the city of Savannah, Georgia.

The snow-white slave cabins at North Hampton in the original St. Johns Parish in Berkeley, South Carolina, show innovation in design. The plantation dates to 1716.

This double slave cabin on Wicklow Plantation in Georgetown, South Carolina, dates to 18251832. The slaves who lived here produced rice for the 190-acre plantation on the North Santee River.

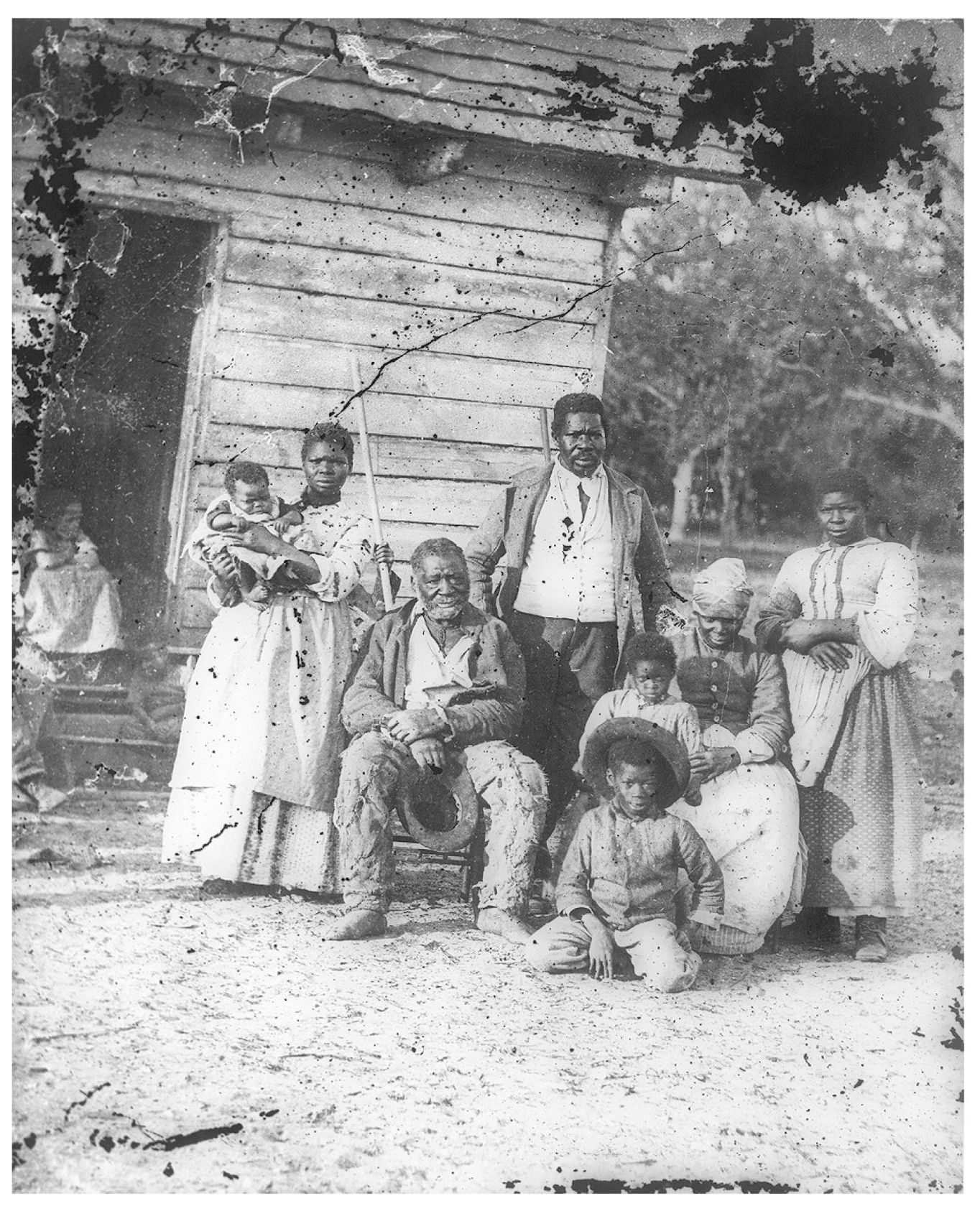

Five generations of this family were photographed together outside a cabin on Smiths Plantation near Beaufort, South Carolina, in 1862.

THE MUMMY AND THE LOST TRIBE

A mummy is in the museum in Charleston. The preserved remains from ancient Egypt date back to around 30 B.C. The black linen on the face has been removed to show the features of a 20- to 40-year-old woman. Through the empty eye sockets, a person can almost see into the hollow darkness of the ancient Africans head. According to the beliefs of this persons culture, her spirit is preserved within.

The mummy in its glass case has been seen by thousands of visitors over the years, with mixed reactions. It was bought by Gabriel Manigault in 1912 from a western diplomat who purchased the mummy in a tomb near Cairo, Egypt. Manigault, a descendant of one of the earliest French Huguenot families in Charleston, intended for the mummy to be shown in the museum to give locals an appreciation of ancient North African culture.

A few years ago, a healthy, 35-year-old tourist from Mississippi stepped into the museum for his first look at the mummy. He moved close to the case and stared intently at the black face. Nobody will ever know what he saw. Within moments, the man collapsed on top of the glass.

The man was still standing on both feet when museum guards arrived. The upper half of his body was resting on top of the mummys glass case, just as they had seen him on their security monitors.

At first the guards were more worried about vandalism to the mummy, but when they saw the mans face, they alerted the head of the museum to close down and called for an ambulance.

When I first heard about the Egyptian mummy and the Mississippians unexplained heart attack, I had recently interviewed an immigrant from Nigeria for this book. Haunted Plantations was in its early stages and my aim was simply to research evidence of supernatural activity in the spotty historical records of slavery and plantations.

I was teaching British literature to senior students at Eau Claire High School in urban Columbia at the time and living in a small nearby town called Camden. One day I needed a taxi to go from Eau Claire to the Columbia airport to pick up a rental car. After completing my overview of the European tribes in Beowulf for my last class of the day, I stepped outside to the waiting cab.

The drivers name was Tafawa. I asked him where he was from when I noticed his thick West African accent. He said he was a member of the modern-day Igbo people of Nigeria. He came to South Carolina because he had family roots here dating back to the 17th century.

Tafawa spoke about his life in West Africa compared with his life now in the United States. Technology made it possible for him to communicate easily with family members on both sides of the Atlantic. But one of the most fascinating things Tafawa revealed is that the Igbos lineage can be traced directly back to Israel.