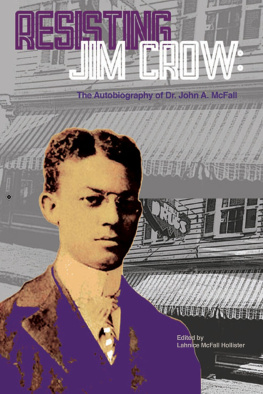

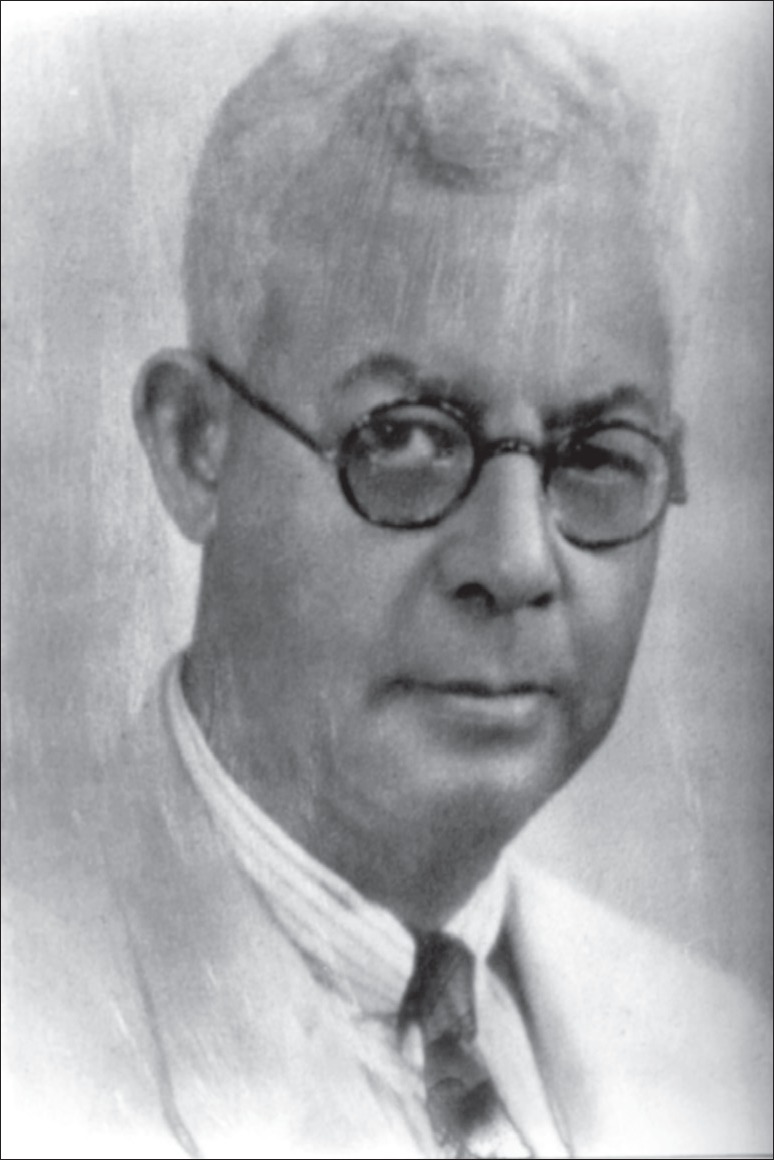

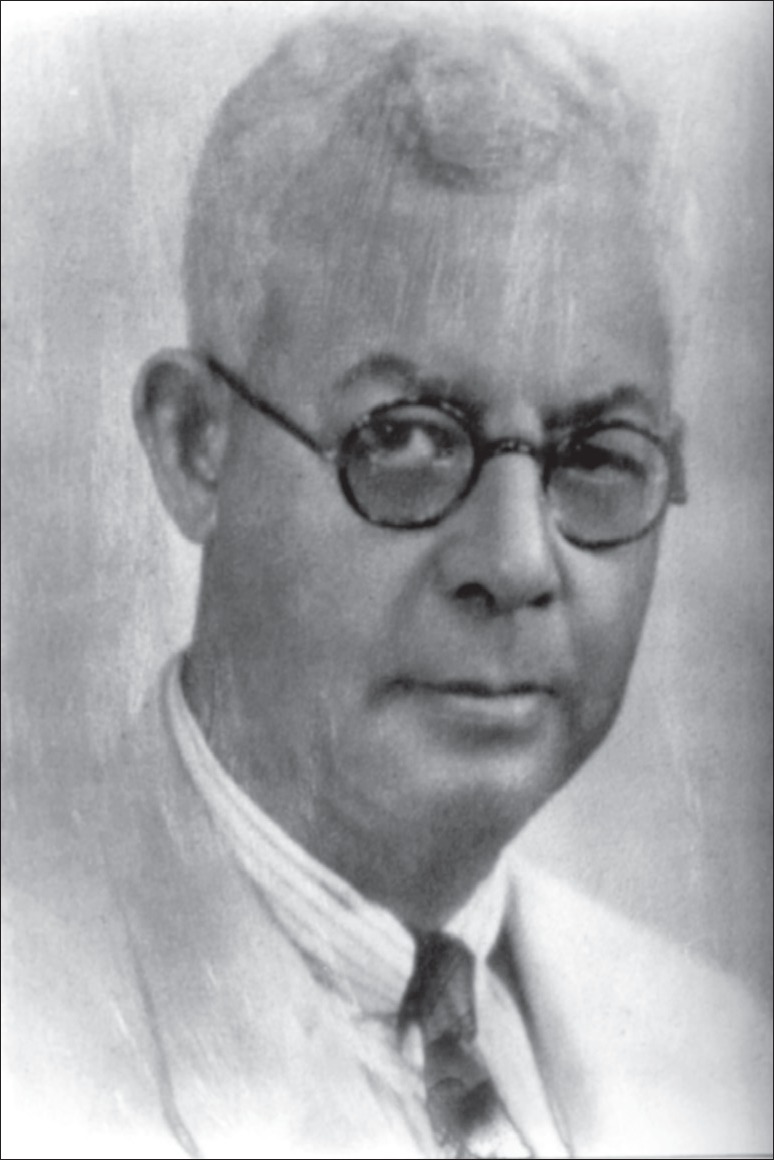

Dr. John A. McFall, circa 1940s when he wrote this autobiography

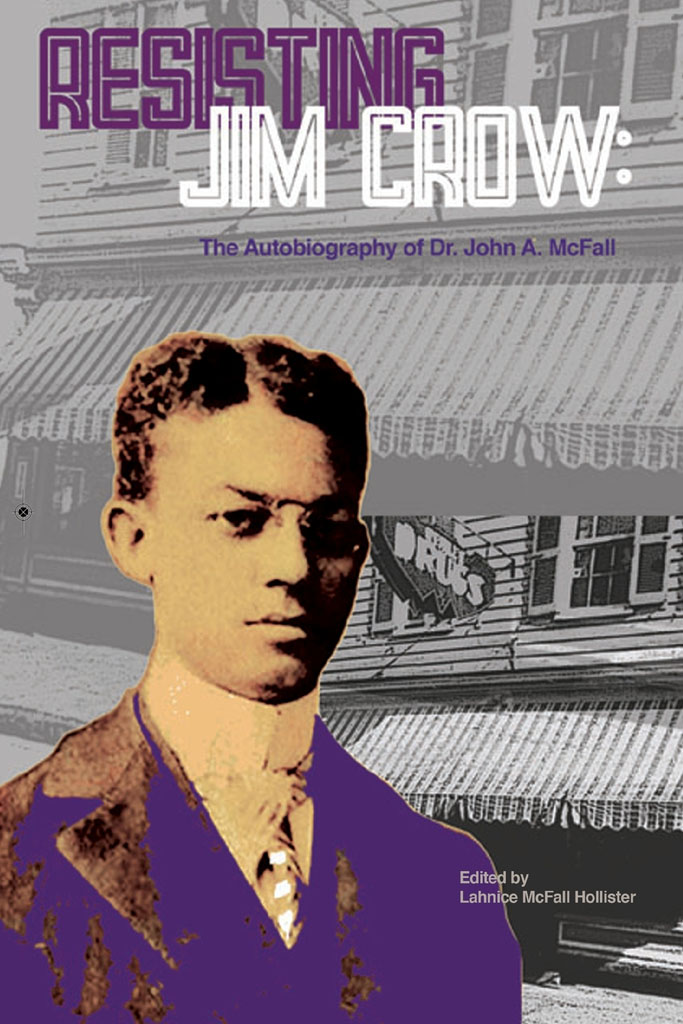

RESISTING JIM CROW: THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF

DR. JOHN A. MCFALL 2021 Morna Lahnice Hollister

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout prior written consent of the copyright owner.

KITTAWAH PRESS LLC, SIMPSONVILLE, SC

Editorial and design services provided by

Modern Memoirs, Inc.

www.modernmemoirs.com

Lauren Nivens Creative

www.lnivens.myportfolio.com

Cover design: Karen Powell

www.powelldesign.com

ISBN: 978-1-7376813-1-1

ISBN: 978-1-7376813-2-8 (e-book)

LCCN: 2021918547

To Mother

Whatever she commanded was complied with,

whether I liked it or not,

and so whatever I am is due largely to her.

Dr. John A. McFall

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Publishing the autobiography of Dr. John A. McFall, the brother of my much-loved grandfather, Paul McFall, is not ancestor worship. It is published by necessity given the lack of African American voices within history books.

John McFall was born in Charleston, South Carolina in 1878the year after the disputed gubernatorial election that marked the end of Reconstruction in the state. He was the first of eleven children born to a Black couple and was among the first generation born in freedom in South Carolina. By the time he reached manhood, African American men were being disenfranchised and all Black people were essentially designated second-class citizens. He tasked himself with resisting the Jim Crow laws that were crippling the political and economic strides women and men of African descent had made in the first decade after Emancipation. He died in 1954two months after the Supreme Court issued its landmark decision in the Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation case on May 17th of that year. This volume contains Dr. McFalls never-before-published manuscript in which he eloquently reports on events between those milestones.

Much has been written about the cruelties and the violence in the Jim Crow South. Dr. McFalls first-person account provides bricks and mortar to assemble a more comprehensive view of this nations past. He makes this history personal by offering his account of how legalized racial segregation was infused into a Southern city. He tells about growing up in a tightly knit family, playing on Charleston streets and waterways, and attending Charleston schools. As a future pharmacist working his way through college in Philadelphia, John was told that his color barred him from jobs for which he was qualified. Upon earning a Doctor of Pharmacy degree from the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and returning home, he encountered similar challenges faced by other Black Charlestonians. Being intelligent and law-abiding were not enough. He was male and he was over twenty-one.

But he was not white.

Therefore, he was not entitled to even the common courtesy of being called Mister or Doctor by any white person, whether man, woman, or child. Dr. McFall met adversity head-on. He insisted on this courtesy for himself and others in the Black community as he navigated the color line and the white power structure. His defeats and victories provide insight into Black agency occurring in Charleston and other urban areas with imbedded, state-sponsored segregation.

I transcribed this manuscript from a digitized copy of the microfilm preserved in the John W. Work III Papers at the Special Collections and Archives of the John Hope and Aurelia E. Franklin Library at Fisk University. That media was at times hard to read and to navigate. This version was created by retyping the entire manuscript. Capitalization, punctuation and spellings were edited for consistency. Illegible text and transcription comments are bracketed [ ]. Headings, a table of contents, an index, and photos were also added. Otherwise, Dr. McFalls original text is unchanged. Researchers are encouraged to consult the files at Fisk.

Dr. John A. McFalls civic activity is also recognized in the following books:

Baker, R. Scott. Paradoxes of Desegregation: African American Struggles for Educational Equity in Charleston, South Carolina, 1926-1972. University of South Carolina Press, 2006.

Drago, Edmund. Initiative, Paternalism, and Race Relations: Charlestons Avery Normal Institute. University of Georgia Press, 1990.

Lau, Peter F. Democracy Rising: South Carolina and the Fight for Black Equality Since 1865. University Press of Kentucky, 2015.

Morna Lahnice McFall Hollister Simpsonville, South Carolina June 2021

PREFACE BY JOHN A. MCFALL

My children have often expressed the wish that I would write the story of my life and its experiences, both personal and public, and to record therewith something about the life and civic activities of the Negro group in Charleston during my time. In compliance with their wish, I give them this narrative. None of it is for publication, as it is written solely with a desire of giving them pleasure, information and perhaps a clearer understanding of the reasons behind some of my acts, especially those concerned with the Charleston Mutual Savings Bank. In recounting these events, I have relied entirely upon memory as I have no other records to draw upon, which makes me mindful of what has often been said of memorythat it is fickle and cannot be relied upon. Perhaps there is some truth in that statement, since time, in its ever-changing cycles, may minimize or may exaggerate the importance of earlier events. This possibility has been kept in mind, and so I have sought to avoid mere conjecture whenever or wherever supporting evidence was lacking. Instead of presenting merely a chronicle of passing events, I have endeavored to associate them with the environmental surroundings of their time, especially the economic, political, social and religious onesa good bit of which I knew from personal experience and some that were a part of the customs, traditions and mode of life that were prevalent during my early life.

I use this pattern because I believe that it alone can give a clear picture of the advancements that had taken place within the Negro group in Charleston during the first twenty-five years following the emancipation, and also to present a later picture that had its beginning depiction in the rising flow of which enveloped Charleston in 1895 and which, with the support of the United States Supreme Court decisions, deprived the Negroes of their political rights, fostered ill will between the races and ultimately succeeded in seriously impairing the Negroes economic status.

An agrarian movement led by Governor Ben Tillman (18901918) characterized by white supremacy and violence against Black people.

Early Years

I was born fifteen years after Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, from ancestry which fades into the usages and customs of slavery. We have a photograph of my great-grandfather, on Fathers side, Ancestor we named him. And from him down to my grandchildren are six generations who bear or have borne the name McFall. On Mothers side there is the recollection of my great-grandmother and the more intimate grandmother who never spoke about the days of her enslavement, but who was brave enough to leave her rural home in upper South Carolina and move away to begin life anew, bringing with her, her mother and her children, Mary Ann, Henry, Paul, Lizzie and Charlotte. Perhaps she was also accompanied by other relatives for when she ultimately reached Charleston, after living a while near Summerville, in the Bacons Bridge area, there around a number of cousins whose relationship is more or less vague. Among them being Cousin Mary Ann Green, Cousin Bella and even more remote than them was one who gave rise to a brass ankle clan at Bacons Bridge.