Preface and Acknowledgments

First, I must express my appreciation to my late wife, Patricia Tyler Lare. Her skills and experience have been helpful to the project in a myriad of ways, but most important, she kept our personal lives on track and in order so that I could maximize my time for this anthology. Without her patience and understanding, such a daunting task would not have been possible. She and other members of my family have freely gone without my time and attention across the years of this project. I am profoundly grateful to them.

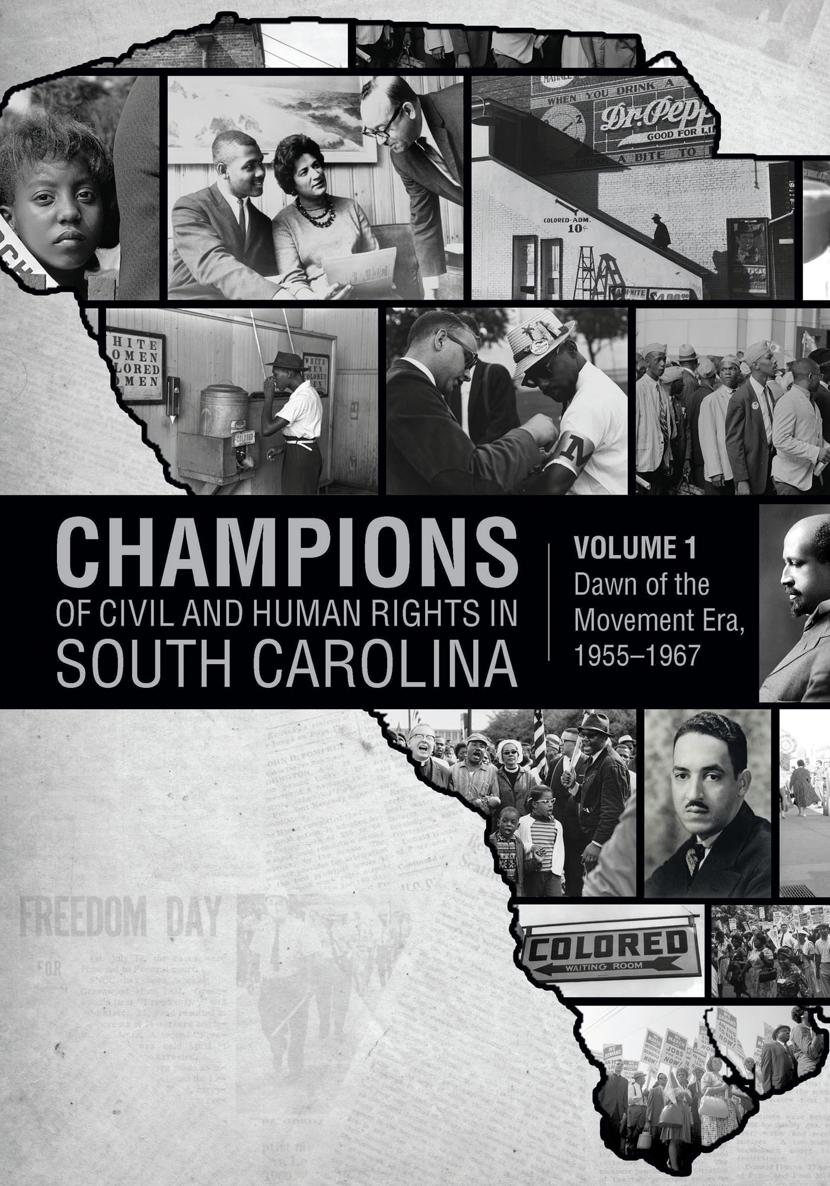

Perhaps the best and most interesting way to provide an overview of this anthology and acknowledge my debts in preparing and publishing it is to tell the story of its origins and development. My anthropology/sociology professor at Southern Methodist University was fond of intoning, Origins are always lost in mystery! Fortunately, while Champions of Civil and Human Rights in South Carolina certainly has many sources, its origin as a project is quite clear.

In April 2003, as I approached retirement from my position with the South Carolina Department of Social Services, I attended a meeting of the board of directors of the Palmetto Development Group. William Bill Saunders was a fellow board member, and when he heard that I was retiring, he inquired, What are you going to do when you retire? I gave him my standard joke that I was going to read one third of my time, garden one third of my time, write a third of my time, and travel a third of my time. He went right past the joke and asked what I was going to write about. I replied that I wanted to address some theological issues but that I might write about the Luncheon Cluban interracial, interfaith group that had been meeting since the early 1960s. He said that he had been writing about the 1969 Charleston Hospital strike, in which he had been a key figure.

On my way home from the meeting, I reflected on the fact that the leaders of the civil rights movement, like the subjects of Tom Brokaws Greatest Generation, were rapidly passing from the scene; aging and death were catching up with them. I pulled over to the emergency lane of the interstate and wrote in my notebook, Anthology of Civil Rights in South Carolina. As I drove on home, I began listing in my mind a dozen or so persons who should be included in such a book.

A week or two later I went to Bills officehe was chair of the state Public Service Commission at the timeand discussed my idea with him. He encouraged me but insisted that the title should include Civil and Human Rights. Discrimination, he pointed out, was not solely a civil matter but a matter of inhumanity, threatening the very lives of those who were its victims. He pulled from his files the 1955 state legislation that made it illegal for any public school teacher or state employee to belong to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

I continued to think and talk with Bill about the project. I reasoned that it was the type of thing the University of South Carolina Press might have an interest in publishing, but I did not know anyone there with whom to discuss it.

Toward the end of May, I took my remaining vacation time for a trip to England and Ireland as a good way to wrap up my employment with the state. On the flight to London, my wife and I sat beside a young British woman, Nicole Mitchell. I was surprised to discover that she was the director of the University of Georgia Press. My heart raced as I thought how I might appropriately broach the subject of my project with her. Finally, I described my retirement project and asked if it would be appropriate for publication by a university press. She indicated that it would and suggested that I contact her friend and colleague, Curtis Clark, who had recently come to head the University of South Carolina Press. She indicated that she and Curtis had been associate directors at the University of Alabama Press and had recently taken new positions in Georgia and South Carolina. I then recalled reading an article to that effect a few months before, written by Bill Starr. I contained my enthusiasm and indicated that I would pursue that contact.

Toward the end of the summer I contacted Curtis Clark and, on September 8, 2003, met with him and Alexander Moore, acquisitions editor for the press. We discussed the concept, and they encouraged me to proceed. In subsequent meetings with Moore, he made numerous practical suggestions, including establishing an official connection with the university through the Institute for Southern Studies. Thomas Brown and Robert Ellis assisted me with that.

It was apparent to me that while I had been personally involved in civil and human rights activities for decades, I was not fully aware of what was afoot in South Carolina relative to my proposed initiative. I did not want to duplicate the efforts of others and hoped that what I did would be complementary. Therefore, during September, October, and November 2003, I consulted people across the state to find out what they were doing in this area and ask their advice and counsel regarding a proposed anthology of the stories of leaders of civil and human rights activities in South Carolina. Listed here are those I consulted during this early period, arranged in alphabetical order rather than in the order I contacted them: Jack Bass, College of Charleston; Marcus Cox, the Citadel; W. Marvin Dulaney, College of Charleston and the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture; Charles Gardner, City of Greenville (retired); William Hine, South Carolina State University; Robert J. Moore, Columbia College (retired); Winifred Bo Moore, the Citadel; Steven ONeil, Furman University; Cleveland Sellers, University of South Carolina; Claudia Smith-Brinson, the State newspaper; Selden K. Smith, Columbia College (retired); and Bernie Wright, Penn Center.

In addition to discussing the content and methodology of the anthology, I inquired about an appropriate home for the project: a public or private nonprofit sponsor with which I could work and secure grant funding. The name of Fred Sheheen came up repeatedly. The former director of the South Carolina Commission on Higher Education, Sheheen was now associated with the Institute for Public Service and Policy Research (IPS&PR) of the University of South Carolina. I had previously worked with him on a number of projects and had been impressed with his vision and leadership.