HarperCollins Publishers

7785 Fulham Palace Road

London, W6 8JB, UK

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by Collins 1999

All rights reserved. Collins Gem is a registered trademark of HarperCollins Publishers Limited

The Foundry Creative Media Co. Ltd 1999

Created and produced by Flame Tree Publishing, part of

The Foundry Creative Media Co. Ltd

Crabtree Hall, Crabtree Lane, London SW6 6TY

All pictures supplied courtesy of James Mackay, except pp 36, 38, 44, 45, 48, 50, 53, 107 courtesy of Stanley Gibbons Ltd.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780004723457

Ebook Edition OCTOBER ISBN 9780007554898

Version: 2013-10-30

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Swedish coil stamp, designed by H. Hallander and engraved by Lars Sjooblom.

S TAMP-COLLECTING has been called the king of hobbies and the hobby of kings a reference to the fact that George V of Great Britain, Carol of Romania and Farouk of Egypt were keen collectors. Other famous philatelists were President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the actors Peter Cushing and Yul Brynner. It was and still is the king of hobbies, with over three million collectors in the United Kingdom, five million in Germany, 12 million in the USA, and probably up to 100 million worldwide.

Of course there is a wide difference between the millionaires who compete for the great rarities in the saleroom and the schoolchildren who save the stamps off their mail and put them in a drawer, hoping that some day they will find the time to sort them and put them into a proper album. In between there are the people who buy new issues across the counter of their friendly neighbourhood post office, perhaps buy a stamp magazine occasionally, send first-day covers to themselves, subscribe to the new issue service of a philatelic bureau or join a local stamp club.

The beauty of stamp-collecting is that it is so flexible. It is an absorbing hobby for young and old alike. You could spend millions of pounds chasing the great rarities, but you would probably have just as much fun tracking down nicely used examples of the latest commemoratives from your office mail.

Stamp-collecting began almost as soon as stamps appeared in Britain, in May 1840. Dr John Gray of the British Museum noted in his diary that month that he had purchased examples of Penny Blacks and Twopenny Blues, not to put on his mail but to keep for their historic interest, so he can fairly be regarded as the first stamp collector. As early as 1842 Punch was noting that young ladies were saving used stamps to decorate plates, screens and even entire walls.

By 1852 a Belgian schoolmaster was advising his pupils to collect stamps as a means of learning geography. Within a decade the first magazines, catalogues and dealers were established. The Philatelic Society of London (now the Royal) was founded in 1869 and has flourished ever since.

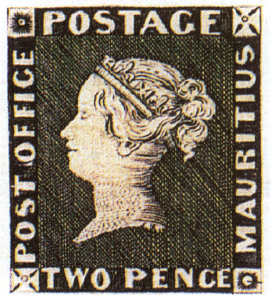

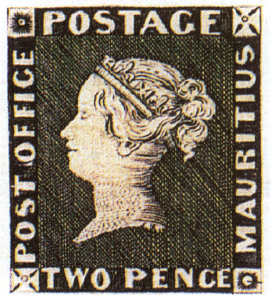

The Mauritius Post Office 2d, 1847.

A souvenir cover from one of theGraf Zeppelinflights.

Stamp-collecting even acquired a pseudo-scientific name philately, coined by the Frenchman Georges Herpin from two Greek words and literally meaning a love of no tax. The Greeks themselves have dropped the negative a and prefer the word philotelia, a love of taxes!

T HIS BOOK contains a wide variety of information about stamps of all kinds, from 1840 to the present day, arranged in a dozen sections; together with a final reference section providing a guide to identification of inscriptions, foreign alphabets, useful addresses and a glossary of terms.

Each section is colour-coded for easy reference and takes the reader through the basics of the hobby, step by step, from starting a rudimentary collection to aspects of specialised philately. Along the way, helpful advice is given on joining a club, choosing the right album and equipment, as well as the techniques of preparing stamps for mounting and writing up in the album.

Because differences in the technical aspects of stamps can have a dramatic effect on their value, it is important to master the basics of the various printing processes, watermarks, perforation and the other minutiae which distinguish rare or elusive stamps from their common and therefore less valuable counterparts.

British stamp printed by the letterpress method.

There are tips on buying and selling stamps, and on how to use a stamp catalogue. The various approaches to stamp-collecting are explored and the pros and cons of general and specialised collecting, thematics and postal history are outlined. The book goes far beyond government-issued adhesive postage stamps, taking a look at local stamps, revenues and other Cinderellas of philately, postal stationery and postmarks.

The Three Skilling Yellow of Sweden, the worlds most valuable stamp.

The factors which make a stamp valuable are considered, and there is a section dealing with the pitfalls of fakes and forgeries. Finally there is an index which lists every subject covered in this book.

Adhesive postage stamps and postal stationery with impressed or embossed stamps have been around only since 1840, although the postal services, of which they are an outward symbol, go back much farther.

B EFORE 1840, WHEN adhesive stamps were adopted in the United Kingdom, there were marks struck by hand on letters to indicate that the postage had been prepaid, although it was more common for the postmaster to endorse the letter in manuscript, usually in red ink. As a general rule, however, letters were transmitted unpaid, and it was left to the recipient to pay the postage. The amount of postage depended largely on how far the letter had travelled. Weight was not as important as the number of sheets comprising the letter, two sheets meaning double postage, three sheets treble postage and so on. Envelopes counted as an extra sheet, and for that reason very little use was made of them before 1840.

Postal services developed gradually all over western Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. In England the Royal Mail was just that, a service used exclusively by the king and his court. The service was thrown open to the general public by King Charles I in 1635, in a bid to raise revenue without recourse to Parliament. This service was disrupted during the Civil War (164249), but resumed at the Restoration in 1660. The datestamp (see p. 148) was invented in 1661 by Colonel Henry Bishop.

Next page