The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

CONTENTS

For Imogen and Fairy

Because the future is even more important than the past.

Stamps tell stories. They speak to us across generations if only wed stop squeezing them into albums and worrying about their catalogue value, and just listen to their voices instead.

Here are thirty-six that I have found most expressive: some beautiful, some quirky, some baffling, some stained with blood; each chosen because it inspired me in some way. My aim is that, gathered together, their stories will meld into a bigger story, that of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the early days of Queen Victoria to the present.

Welcome to Britain, in thirty-six little pieces of paper.

CHAPTER ONE

IN THE BEGINNING

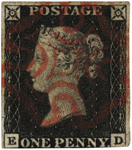

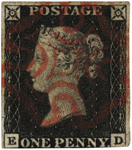

PENNY BLACK, 1840

T HE P ENNY B LACK is the worlds first postage stamp. Fittingly it bears the image of a new, young monarch: this chapter is about beginnings.

The young woman on the Penny Black inherited the crown of a brilliant but troubled nation. Brilliant in its technology and industry thanks to engineers and entrepreneurs like Matthew Boulton and Josiah Wedgwood, this damp and not very big island off the coast of Europe had become the worlds fastest-growing economy. Troubled because of the social problems this Industrial Revolution brought with it: slums, child labour, appalling working conditions and hours. Brilliant in our trading skills and naval power, and the influence these gave us in foreign lands. Troubled because of the responsibilities this brought, and our lack of understanding of how to carry these out. Brilliant in a culture of aristocratic elegance. Troubled in the corruption that can fester in closed elites.

Making sense of this dual legacy would call for creativity, courage and energy. Fortunately, the subjects of the new queen possessed these very qualities. The story of this stamp provides a perfect example.

The penny post was not a Victorian invention. Back in 1680, when London was already a big place with a population of half a million, William Dockwra had guaranteed, for that amount, delivery of a letter within four hours anywhere in the city. This proved such a success that the government quickly nationalized the system, meaning that the profits could be redirected into the pocket of the Duke of York. Fortunately for Dockwra, the Duke became king and soon after that was deposed in the Glorious Revolution of 1688, having to flee the country; Dockwra found himself once again running the postal system, this time on a government salary.

Other entrepreneurs followed Dockwras example and set up successful penny post systems in other cities. However, on a national scale the Hanoverian post was a mess. Mail between urban centres was slow; try sending something to the country and it was even worse. The arrival of mail coaches in the late eighteenth century added a dash of glamour, but the system remained clunky. A bewildering list of tariffs and surcharges made the process laborious and prices prohibitive: the average cost of mailing a single written page across Britain was about 8d (old pence), or about 3p in todays money, which doesnt sound much until you consider that a workmans weekly wage was about seven shillings (35p). In modern terms, this is equivalent to paying 40 to send a one-page letter.

The only benefit to the sender was that they wouldnt have to pay this. The addressee would do that. This was hugely inefficient: recipients werent always at home, and when they were at home sometimes refused to pay hardly surprising at 40 per letter or simply didnt have enough money to hand. On top of these day-to-day issues, the system was corrupt. MPs and Peers of the Realm could send post for free, and as a result businesses offered them directorships so that they could utilize this perk.

The usual cries of something must be done had been echoing around for a while. But the Victorians didnt just echo, they did things.

Rowland Hill was an exceptional man. He came from one of those marvellous late eighteenth/early nineteenth-century families with a passion for education and reform. His father, Thomas Hill, ran a progressive school on the principles of kindness and patience, where the rules were agreed by an elected committee of boys (Thomas Hill is said to have invented the Single Transferable Vote for this purpose). Science was a core part of the curriculum, as was practical Mathematics, a technology class. English, history, living languages and elocution were also taught to ensure a rounded education, whereas Latin and Greek, which were endlessly flogged into pupils at Eton and Harrow, were optional.

Hill followed in his fathers footsteps and was running the school by the age of 25. He didnt just run it he designed new premises for it, which included such innovations as gas central heating, a swimming pool, an observatory and craft rooms. The new school attracted international attention and pupils from Europe as well as the UK. Alongside his educational work, Hill developed a rotary printing press, a speedometer for stagecoaches and a propeller for ships, and co-founded the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, an inventors club, another of whose members was Charles Wheatstone, whom we will meet again later in this story.

Hill also interested himself in public matters, writing a tract on poverty relief in the UK, suggesting ways in which poor but enterprising people could emigrate safely to Australia. Up to that point, emigration had been a disorganized business, with unscrupulous shipowners overloading ships and underfeeding passengers. Hill recommended checks on the suitability of both migrants and carriers, and a new system whereby carriers were paid for the number of passengers who arrived safe and well in Australia. As a result of his work, he was made Secretary of the South Australian Colonization Commission. Thanks to Hills influence, the new colony was set up with a charter ensuring religious freedom and civil liberties.

In his spare time not that he had much he was a distinguished amateur artist.

According to legend, Hill first became interested in Post Office reform as a boy, when the postman turned up at his family home wanting three shillings for a bundle of letters. Young Rowland had been sent into Birmingham to sell some old clothes to raise the cash. Now, as an adult with a track record in social improvement, Hill turned his attention to the topic once again, and wrote his famous pamphlet, Post Office Reform, its Importance and Practicability . When attempts to interest the Post Office in this failed, Hill had it published privately. It soon came to public notice, and the authorities were forced to pay attention.

Hills vision was bold. The old system of complicated tariffs would be swept away and replaced by a simple national rate: send a letter anywhere in the UK and it would cost a penny. Rather than one sheet, which is all you could afford in the old days, you could send a letter weighing up to half an ounce (about the weight of two sheets of modern A4); any more and you only had to pay an extra penny. The system would be based on payment in advance and the old system of free postage for select groups was to be abolished.