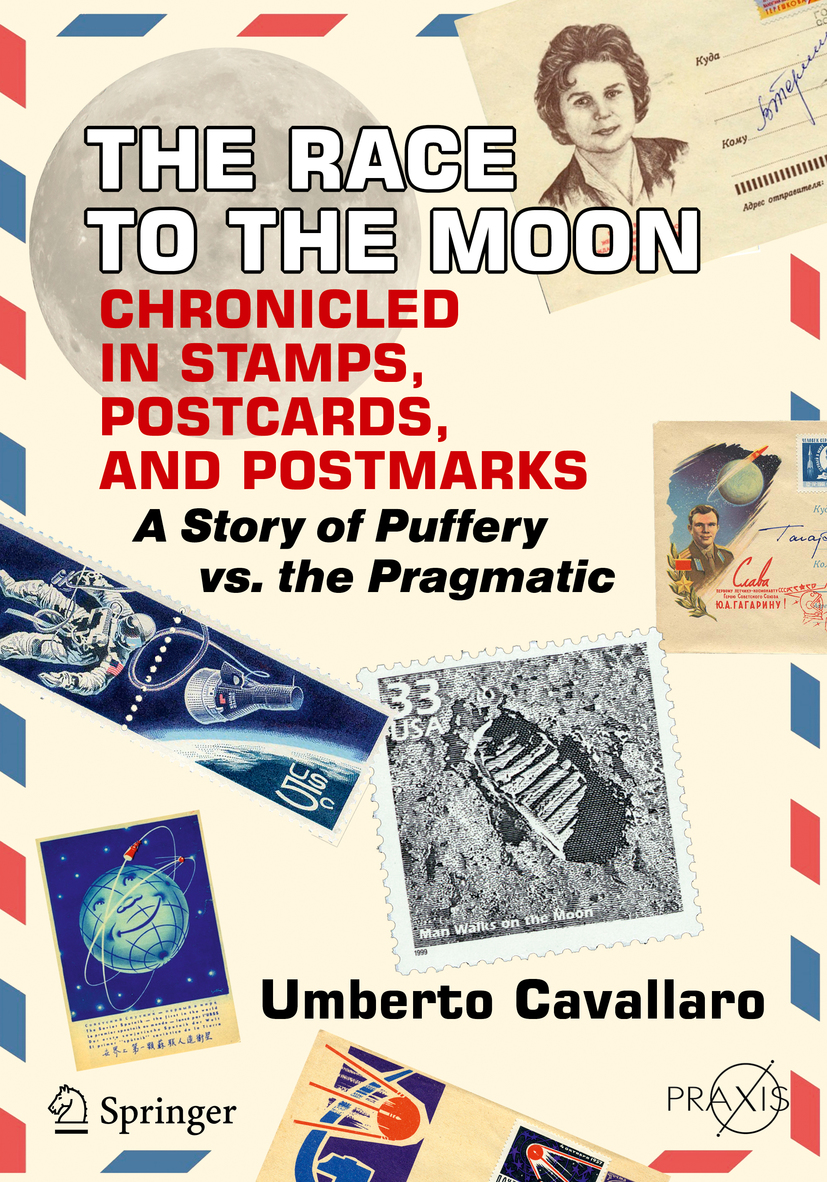

Springer Praxis Books Space Exploration

Umberto Cavallaro

The Race to the Moon Chronicled in Stamps, Postcards, and Postmarks A Story of Puffery vs. the Pragmatic

Umberto Cavallaro

Italian Astrophilately Society, Villarbasse, Italy

Springer Praxis Books

ISBN 978-3-319-92152-5 e-ISBN 978-3-319-92153-2

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92153-2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018954650

Original Italian edition published by Edizioni Visual Grafika, Torino, 2011

Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2018

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed.

The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.

The publisher, the authors, and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Cover design: Jim Wilkie

Project Editor: Michael D. Shayler

This Springer imprint is published by the registered company Springer Nature Switzerland AG

The registered company address is: Gewerbestrasse 11, 6330 Cham, Switzerland

To Anna Yukiko

Who will eye-witness

What we only dared to dream.

Foreword

Reading this book brought me back to the wonderful and intense years I spent at NASA when the events described by Umberto were taking place. It reminded me of the enthusiasm, the emotions, anxiety, expectations, frustration, and elation of those golden years when I was living them.

The book presents the two different worldviews confronting each other at the turn of the 1950s, when two superpowers came together in a head-to-head competition. Fortunately, the rivalry extended beyond our planet and slid into a more peaceful battlefield. Sputnik had changed the direction of American science and had touched all our lives, but the awakening that triggered a heated space race was, in the United States, the launch into space of Yuri Gagarin on Vostok 1 in April 1961. A few weeks later, American President John F. Kennedy announced that America was going to land a man on the Moon within 10 years.

We ran all the way keeping an eye on the Soviets, feeling their breath on our necks. Still, by the summer of 1967 we believed that, in the unproclaimed race to the Moon, the Russians were ahead of the United States. When Russia launched Zond 5 in September 1968, we worried that it was a prelude to an imminent Russian manned flight around the Moon and, eventually, a lunar landing. The Soviets had upstaged us so often that NASA was concerned that they would attempt their own manned circumlunar mission prior to the United States.

Only years later, when the United States and Russia began to move closer together with the joint Apollo/Soyuz Program and to an even greater degree when American astronauts participated in the Russian Mir space station program did we begin to understand the limitations of the Russian space program and the differences between the way our two countries were exploring space. As the book captures well, there was a radical difference in the human approach to space exploration. Early astronauts successfully fought for more human involvement and manual control of the spacecraft. Early cosmonauts were basically passengers on missions where operational activities were almost exclusively handled by ground controllers. Cosmonauts were sometimes perceived as a troublesome substitute for an onboard sequencer. The Soviets never fully trusted the cosmonaut crews as opposed to their ground collective support. The philosophy of central control led to the pecking order of ground over crews.

An automatic orbit and recovery was no more appealing to an astronaut in 1960 than automatic landings are today to a passenger on a commercial airliner. This attitude may have been a factor in one of the most obvious differences between the American and the Russian manned space programs: The Soviets returned from manned space missions on land, while in America we splashed down in the ocean. As a result, the Soviets developed relatively simple hardware and flew relatively simple missions. It was a real eye-opener to us in the Astronaut Office when we learned that so many Russian firsts had been accomplished, and they had gained such worldwide prestige, with such simple hardware. (It was one of the few areas where we could learn from them.)

An interesting side point is that philately that at the time was a sort of national pastime, both in the USSR and in the USA was heavily used by Soviets for propaganda purposes. Secrecy and propaganda, used with fantasy, or if you want with creativity, helped to mask the differences, and the limits, for years.

With the Apollo 50th anniversary approaching, thank you, Umberto, for doing this history!

Walter Cunningham, Apollo VII

Acknowledgments

Among the many friends who have supported me in this effort, I must especially thank Jeff Dugdale for his patient first revision of this manuscript and for his precious comments and suggestions.

Thanks also to the many collectors who helped me to document this history by making available some unique items from their collections: Dave Ball (USA); Chris Calle (USA); Pietro Della Maddalena (Italy); Dennis Dillman (USA); Steve Durst (USA); Don Hillger (USA); Peter Hoffman (USA); Walter Hopferwieser (Austria); the late Viacheslav Klochko (Russia); Jaromir Matejka (Austria); Stefano Matteassi (Italy); Renzo Monateri (Italy); Renato Rega (Italy); Jim Reichman (USA); and Antoni Rigo (Spain).

A special thanks to former NASA astronaut Walter Cunningham for his contributions to this book, especially the Foreword. I was also honored to have him attend the presentation of the first version of this manuscript when it appeared in Italian some years ago.

A final thanks to Mike Shayler, who added value to the text with his professional editing and his friendly advice.

Unless otherwise indicated, the pictures of collectibles (covers, stamps, cards, posters, mission patches, manuals, etc.) are from the collection of the author. Despite extensive research, the author has been unable to trace the exact origins of some of the images used in this title and would welcome any assistance that would enable him to credit the appropriate sources.