Publisher: Amy Marson Creative Director: Gailen Runge Art Director / Cover Designer: Kristy Zacharias Editor: S. Michele Fry Technical Editors: Ann Haley, Gailen Runge, and Susan Hendrickson Book Designer: Kristen Yenche Production Coordinator: Rue Flaherty Production Editor: Katie Van Amburg Illustrator: Salley Mavor Photo Assistant: Mary Peyton Peppo ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND DEDICATION Dedicated to my sister, Anne Mavor, who still shares her imagination. To my husband, Rob Goldsborough, for taking the photographs in this book and for his constant support and encouragement; to our sons, Ian and Peter; and to my late parents, Mary and Jim Mavor, for instilling a sense of wonder and believing in the value of art.

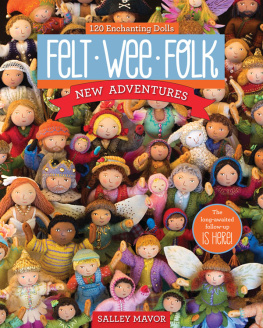

ince Felt Wee Folk: Enchanting Projects was first released in 2003, thousands of hand-sewn fairies and wee folk have been created, populating every corner of the world. I have heard stories from many people who tell how the projects have brought joy and comfort to individuals of all ages and skill levels. From their accounts, the experience of making these little dolls is not only fun but also meaningful and therapeutic.

ince Felt Wee Folk: Enchanting Projects was first released in 2003, thousands of hand-sewn fairies and wee folk have been created, populating every corner of the world. I have heard stories from many people who tell how the projects have brought joy and comfort to individuals of all ages and skill levels. From their accounts, the experience of making these little dolls is not only fun but also meaningful and therapeutic.

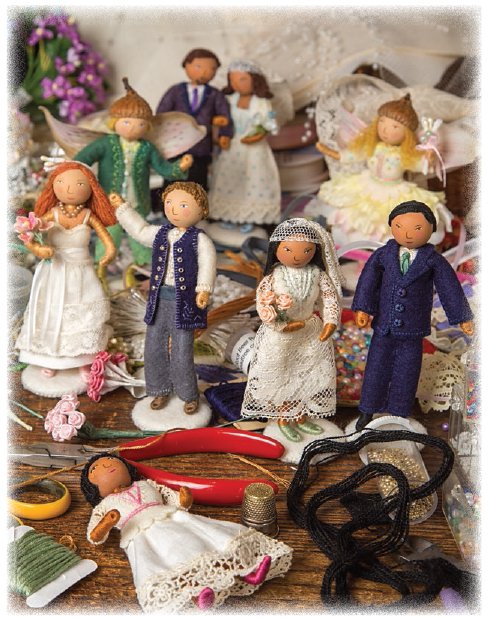

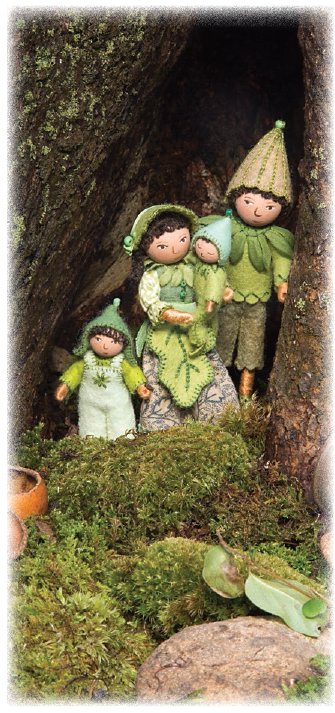

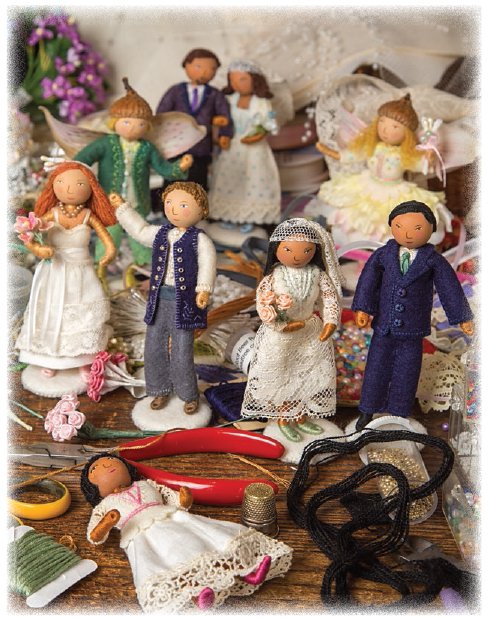

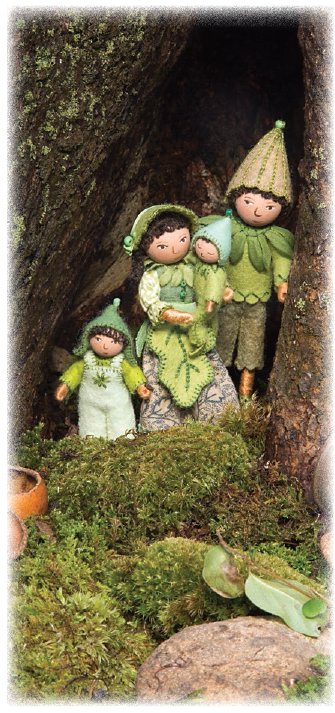

It warms my heart to read about kitchen tables, shady summer lawns, and white hospital beds covered with flower petals, pipe cleaners, and floss, and busy fingers wrapping and stitching wee folk dolls. Creating a miniature world appeals to a certain type of person, and I have found out that there are a lot of us! These dolls connect to the child in all of us. I originally wrote the book with adults in mind and have heeded the call for more challenging projects. This new edition expands the wee world, with pictures, directions, and patterns for making more characters with a variety of hairstyles, outfits, and accessories. The projects in this book include little figures that might inhabit enchanting miniature scenes, from flowery Blossom Fairies to a fully outfitted Robin Hood to wedding couples dancing atop a cake. This expanded all-doll edition shows more ways of constructing armatures and attaching hair, as well as instructions on making doll stands, which open up new possibilities for displaying the dolls.

You will find step-by-step directions for constructing different sizes of bendable doll bodies with painted wooden bead heads. With the basic wrapped chenille stems (pipe cleaners) as a foundation, an unlimited assortment of characters and personalities can come to life with wool felt and faux (or silk) flower petal costumes.  The ideas on the following pages are for needleworkers of all ages and skill levels, from the beginner who is learning the blanket stitch to the experienced embroiderer who relishes fine stitching. There is plenty of room for adapting the details of the designs to make each little doll as individual as its maker. The figures can be used in countless ways, from dollhouse play to setting up special scenes that will be cherished year after year.

The ideas on the following pages are for needleworkers of all ages and skill levels, from the beginner who is learning the blanket stitch to the experienced embroiderer who relishes fine stitching. There is plenty of room for adapting the details of the designs to make each little doll as individual as its maker. The figures can be used in countless ways, from dollhouse play to setting up special scenes that will be cherished year after year.  THE AUTHORS STORY

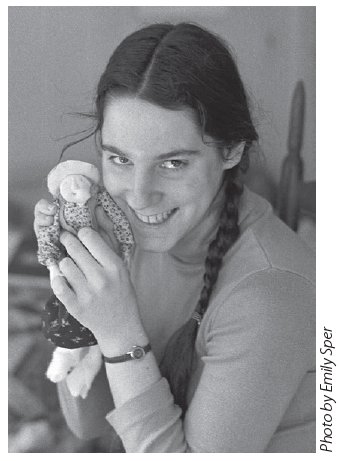

THE AUTHORS STORY  Salley at Rhode Island School of Design, 1977

Salley at Rhode Island School of Design, 1977  y favorite way of working is in mixed media.

y favorite way of working is in mixed media.  THE AUTHORS STORY

THE AUTHORS STORY  Salley at Rhode Island School of Design, 1977

Salley at Rhode Island School of Design, 1977  y favorite way of working is in mixed media.

y favorite way of working is in mixed media.

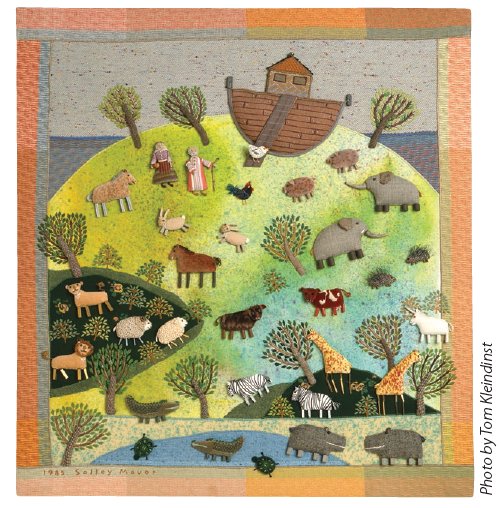

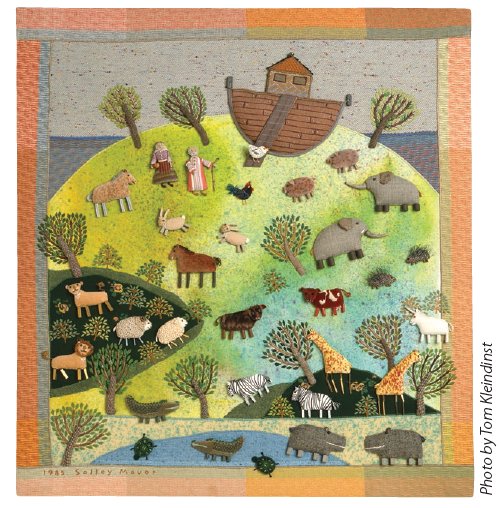

For as long as I can remember, I have felt that my pictures were plain and unfinished unless something real was glued, stapled, or sewn onto them. I have found a method of working that allows me to explore and play with a variety of supplies and techniques. Although I have no set formula, the common thread in my work is, well, thread. I embroider, wrap, and sew felt and found objects together, creating three-dimensional scenes in relief that are photographed and reproduced in picture books and on posters and cards. Growing up in a home full of art, music, and dance contributed to my belief that creative expression is a fundamental part of life, defining who we are as individuals and as a society. When I was a little girl, my sister and I spent countless hours creating a miniature world with our toys and found objects.

Scraps of cloth, old buttons, snaps, and eyehooks became clothes, accessories, and furnishings for our dolls. Our measure of excellence was the impeccable doll clothes sewn by our Southern great-aunts, Dell and Alma Salley. We created a roofless, one-floor ranch house on an old oak table for Barbie and our troll dolls. I remember trying to make Barbie sit in a natural position, but all she could do was stick her legs out straight, pointing her pitiful little high-heeled feet upward. The trolls, in contrast, were stable and grounded in their homely squat bodies. The doll table was a major interest for many years, until the onset of adolescence, when our continued attraction to dolls became an embarrassing secret.

It was not until studying illustration at the Rhode Island School of Design that I started to sew and make dolls again. After struggling through a watercolor class, I came to understand that I would never be an illustrator in the traditional sense. I regarded my paintings and drawings not as finished pieces but as a starting point from which to launch an idea. The impulse to add textures and objects was so compelling that I found myself interested only in creating work that had a three-dimensional element. I was aware of a tactile connection to the creative process, much like the synergy of play. It was such a relief to find out that I could communicate my ideas in three dimensions and still be an illustrator.

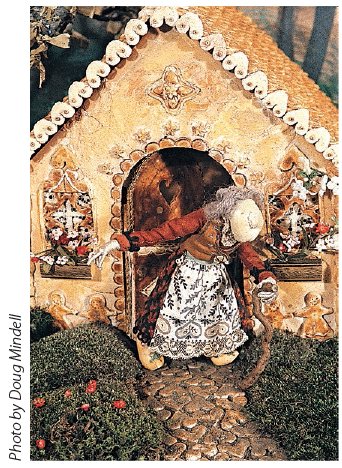

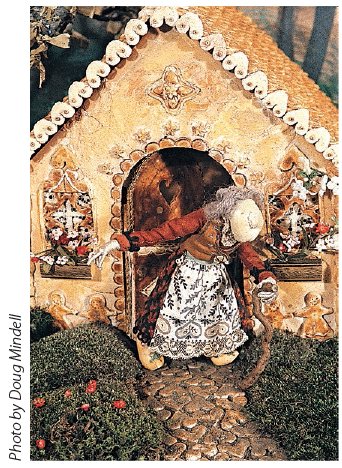

Encouraged by my teacher, Judy-Sue Goodwin-Sturges, I continued to experiment with doll-making and found objects, learning techniques and processes on my own. By my senior year, I was making dolls of all kindsanimals and people with movable limbsand setting them up in scenes to be photographed.  Detail of Hansel and Gretel, 1978, part of my senior thesis After graduation in 1978, I made and sold a line of stuffed fabric pins, designed sewing projects for womens magazines, and worked on a series of homemaker dolls and their stuffed appliances.

Detail of Hansel and Gretel, 1978, part of my senior thesis After graduation in 1978, I made and sold a line of stuffed fabric pins, designed sewing projects for womens magazines, and worked on a series of homemaker dolls and their stuffed appliances.  Fabric pins, 1979 In an effort to have my work recognized more as art than as handiwork, I decided to adapt my technique to a relief format so that it could be presented in a frame. I explored ways of covering cardboard with fabric and formed people, animals, and buildings that were sewn onto a fabric background. My husband, Rob Goldsborough, made beautiful wooden shadow-box frames for the new work.

Fabric pins, 1979 In an effort to have my work recognized more as art than as handiwork, I decided to adapt my technique to a relief format so that it could be presented in a frame. I explored ways of covering cardboard with fabric and formed people, animals, and buildings that were sewn onto a fabric background. My husband, Rob Goldsborough, made beautiful wooden shadow-box frames for the new work.

I welcomed the added challenge of making backgrounds for the figures, keeping a three-dimensional quality to their magical, miniature world behind the glass.

Next page

ince Felt Wee Folk: Enchanting Projects was first released in 2003, thousands of hand-sewn fairies and wee folk have been created, populating every corner of the world. I have heard stories from many people who tell how the projects have brought joy and comfort to individuals of all ages and skill levels. From their accounts, the experience of making these little dolls is not only fun but also meaningful and therapeutic.

ince Felt Wee Folk: Enchanting Projects was first released in 2003, thousands of hand-sewn fairies and wee folk have been created, populating every corner of the world. I have heard stories from many people who tell how the projects have brought joy and comfort to individuals of all ages and skill levels. From their accounts, the experience of making these little dolls is not only fun but also meaningful and therapeutic. The ideas on the following pages are for needleworkers of all ages and skill levels, from the beginner who is learning the blanket stitch to the experienced embroiderer who relishes fine stitching. There is plenty of room for adapting the details of the designs to make each little doll as individual as its maker. The figures can be used in countless ways, from dollhouse play to setting up special scenes that will be cherished year after year.

The ideas on the following pages are for needleworkers of all ages and skill levels, from the beginner who is learning the blanket stitch to the experienced embroiderer who relishes fine stitching. There is plenty of room for adapting the details of the designs to make each little doll as individual as its maker. The figures can be used in countless ways, from dollhouse play to setting up special scenes that will be cherished year after year.  THE AUTHORS STORY

THE AUTHORS STORY  Salley at Rhode Island School of Design, 1977

Salley at Rhode Island School of Design, 1977  y favorite way of working is in mixed media.

y favorite way of working is in mixed media.  Detail of Hansel and Gretel, 1978, part of my senior thesis After graduation in 1978, I made and sold a line of stuffed fabric pins, designed sewing projects for womens magazines, and worked on a series of homemaker dolls and their stuffed appliances.

Detail of Hansel and Gretel, 1978, part of my senior thesis After graduation in 1978, I made and sold a line of stuffed fabric pins, designed sewing projects for womens magazines, and worked on a series of homemaker dolls and their stuffed appliances.  Fabric pins, 1979 In an effort to have my work recognized more as art than as handiwork, I decided to adapt my technique to a relief format so that it could be presented in a frame. I explored ways of covering cardboard with fabric and formed people, animals, and buildings that were sewn onto a fabric background. My husband, Rob Goldsborough, made beautiful wooden shadow-box frames for the new work.

Fabric pins, 1979 In an effort to have my work recognized more as art than as handiwork, I decided to adapt my technique to a relief format so that it could be presented in a frame. I explored ways of covering cardboard with fabric and formed people, animals, and buildings that were sewn onto a fabric background. My husband, Rob Goldsborough, made beautiful wooden shadow-box frames for the new work.