SARAH A. CORBET, SCD

PROF. RICHARD WEST, SCD, FRS, FGS

DAVID STREETER, MBE, FIBIOL

JIM FLEGG, OBE, FIHORT

PROF. JONATHAN SILVERTOWN

The aim of this series is to interest the general reader in the wildlife of Britain by recapturing the enquiring spirit of the old naturalists.

The editors believe that the natural pride of the British public in the native flora and fauna, to which must be added concern for their conservation, is best fostered by maintaining a high standard of accuracy combined with clarity of exposition in presenting the results of modern scientific research.

For Pam for her reading and her patience

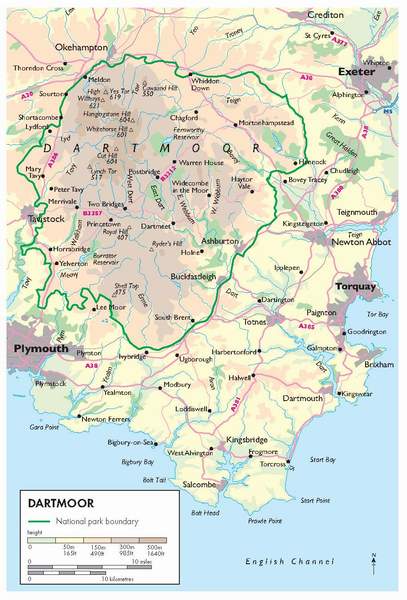

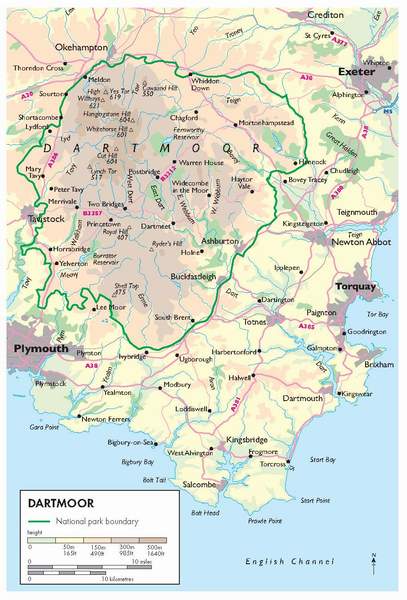

Dartmoor National Park in its immediate setting.

T he British landscape has been a central theme of the New Naturalists library since its inception and was given early expression by volumes devoted to individual national parks. The tradition was initiated by Snowdonia sub-titled The National Park of North Wales, and published in 1949, the same year as the Act of Parliament that established the parks came into being. Dartmoor was created a national park in 1951 and two years later we published Professor L. A. Harveys and D. St. Leger-Gordons Dartmoor as number 27 in the series. Over the next 25 years this ran to three editions and several reprints.

At the time our predecessors wrote that, the competing claims of national defence, water-supply, mineral working, afforestation, hill sheep-farming, public recreation and nature conservation which affect so many of the remoter parts of Britain are here all concentrated in one compact area in the heart of a single county. Today, more than 30 years later, these are still burning issues and all feature prominently in the present volume. However, it is also the case that much has changed and the fruits of new research and a changing political and social environment pointed to the need for a fresh and updated approach to the area.

Professor Mercer is uniquely qualified for this task. As he writes in his Foreword, he has had a long association with the moor since first being introduced to it as an undergraduate in the early 1950s. In 1973, he became the first chief officer of the new Dartmoor National Park Authority, a post that he held for the next 17 years, and he is now chairman of the Dartmoor Commoners Council. Not only that, but he is one of the countrys foremost authorities on national parks and countryside conservation. For five years he was chief executive of the newly formed Countryside Council for Wales and on returning home to Dartmoor was appointed secretary-general of the Association of National Park Authorities.

If all of this sounds like the CV of a typical high-flying bureaucrat, the truth, as the reader will soon discover, is different. Ian Mercer is a geographer and naturalist at heart, never happier than when revealing the secrets of a landscape to a party of entranced and riveted students from the pulpit of a convenient Dartmoor tor or educating the nation on radio from the vantage of a hot air balloon. This is an intensely personal account, written with passion, authority and understanding and in a style that anyone familiar with the author will instantly recognise.

In the preface to the third edition of the original Dartmoor, the authors acknowledge assistance from, among others, a Mr Ian Mercer. With this book another of Ian Mercers Dartmoor circles has been neatly closed.

T HIS BOOK IS ABOUT my perception of a landscape and what knowledge is needed as a foundation to that perception. The landscape in question is that of a compact, discrete, upland national park in Southwest England called Dartmoor and this is my interpretation of its anatomy and at least part of the spectrum of its inhabitants in the twenty-first century fully acknowledging that there are many who know both better than me. This interpretation recognises that all things alive, natural and human (for we have for a long time drawn an artificial distinction between them) may contribute to that perception but I do not dwell upon those things that have, or have had, little impact in the landscape itself. That we now know that moorland is for the most part a human imposition upon the upland, and has been maintained by graziers for some 5,000 years, means that the book necessarily involves itself with the contemporary state of that maintenance, its workforce, their difficulties and their would-be overseers.

I have written for the lay reader, mostly of the secular kind, and have used the language and terminology of whatever stage in the development of scientific thinking I have found most comfortable over my fifty-year intermittent observation of this singular hill. Scientific information and its language, shared for the most part between academic peers, seems to become increasingly abstruse. It is not always amenable to instant translation for the rest of us, and space for long and detailed explanation in a book like this is in short supply. None of this denies the need to delve into the far distant past, or helpful theory of any age, on the many occasions when a better understanding of things seen now is the purpose. Equally where good readable descriptions and explanations already exist I have seen no need to repeat the detail they should be listed near the back of the book.

That said, there is a vast Dartmoor literature with a landscape reference and all that goes with it. It begins with the Domesday Book, but is then patchy for seven hundred years or so. It mushrooms as the nineteenth century progresses and gathers momentum through the twentieth. In the latter part of that century there is an interesting dichotomy. Scientific work on natural and archaeological detail on the one hand increases, and its publication matches its volume, however difficult it is to track down. On the other hand popular writing keeps pace volumetrically, partly because of its huge range: from serious amateur exploration of much moorland detail, through new editions of earlier classics such as the Crossing essays, to a multitude of later guides for walkers, riders and letterbox hunters. (For the stranger: letterboxes, except the nineteenth century original at Cranmere Pool, lie hidden in thousands of locations and contain a rubber stamp whose imprint is the evidence for the success of the hunt.)

Between these two large literary branches runs a slim central procession of general Dartmoor statements of their time, for lack of a better definition. After the unique Domesday essay there is that long gap, but Samuel Rowe, in the Preface to his A Perambulation of the Forest of Dartmoor and its Venville Precincts in 1848, encapsulates the idea and thus really sets off my procession. He says: within its [Dartmoors] limits there is enough to repay, not only the historian and antiquary but the scientific investigator for the task of exploring the mountain wastes of the Devonshire wilderness. He goes on to point to tors for the geologist, Wistmans Wood for the botanist and the aboriginal circumvallation of Grimspound for the antiquary. He does not neglect the economic activity evident on the Dartmoor of his day, but in the thrusting and somewhat innocent Victorian manner concentrates on cultivation and reclamation opportunity and regards common rights as an inhibition to logical ambition in the agricultural developer.

The modern sequence starts, I think, with Worths Dartmoor edited by Malcolm Spooner and the first New Naturalist Dartmoor by Harvey and St Leger Gordon, both published in 1953. Then the Devonshire Association published a volume of (scientific)