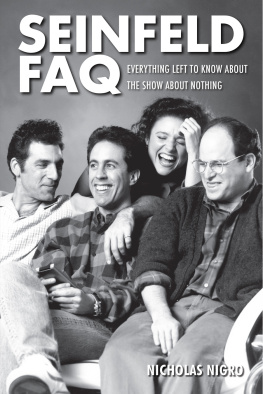

Copyright 2015 by Nicholas Nigro

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, without written permission, except by a newspaper or magazine reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review.

Published in 2015 by Applause Theatre and Cinema Books

An Imprint of Hal Leonard Corporation

7777 West Bluemound Road

Milwaukee, WI 53213

Trade Book Division Editorial Offices

33 Plymouth St., Montclair, NJ 07042

Except where otherwise specified, all images are from the authors personal collection.

The FAQ series was conceived by Robert Rodriguez and developed with Stuart Shea.

Printed in the United States of America

Book design by Snow Creative Services

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nigro, Nicholas J.

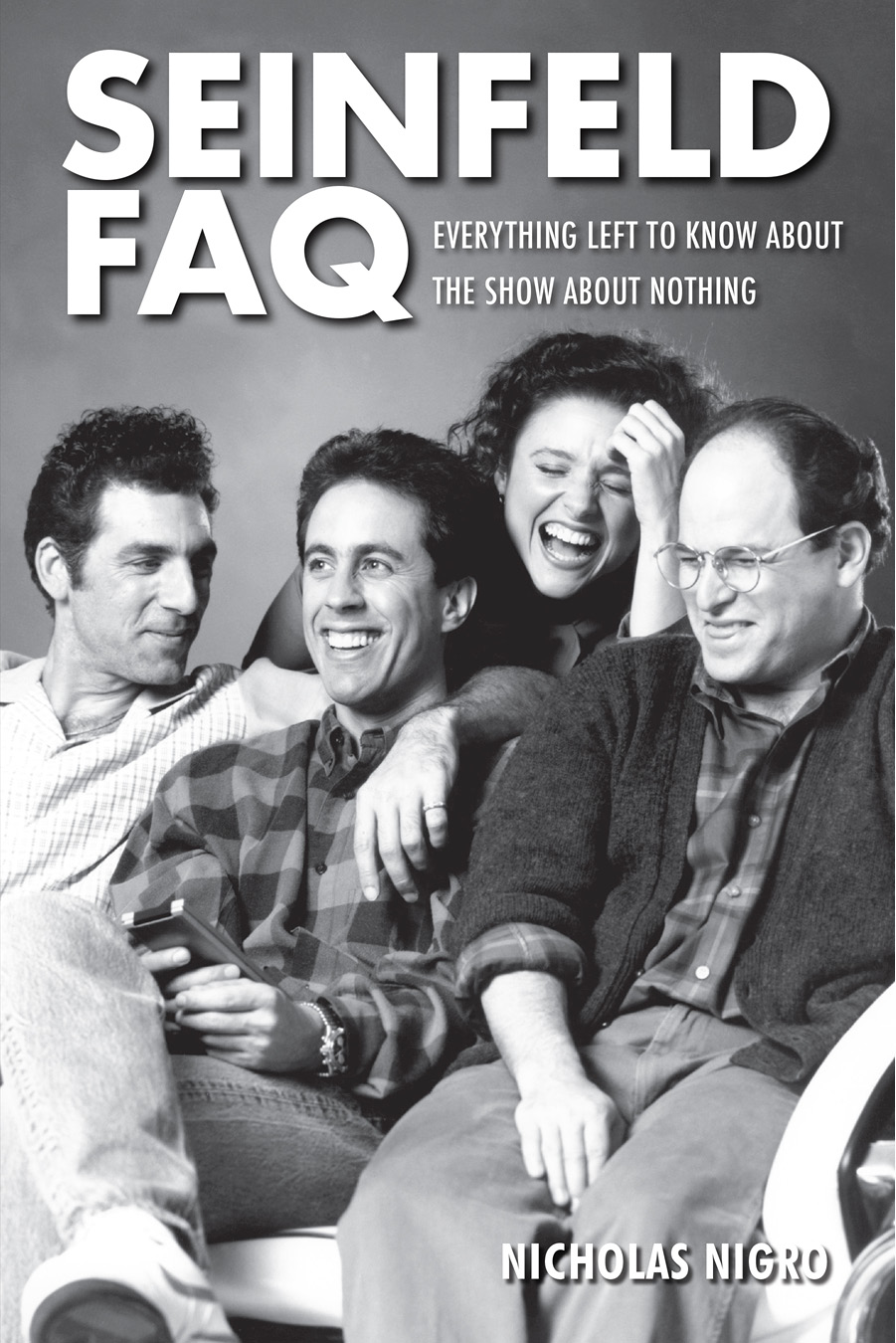

Seinfeld FAQ : everything left to know about the show about nothing / Nicholas Nigro.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-55783-857-5

1. Seinfeld (Television program)Miscellanea. I. Title.

PN1992.77.S4285N54 2014

791.4575dc23

2014027918

www.applausebooks.com

To my father, Nicholas Nigro, who could never get enough of Seinfeld ,

and who proved that the show transcended generations

Contents

Foremost, Id like to thank my agent, June Clark, for pitching me for this project and for helping me achieve my original dream as a writerto author a television book. And not just any TV bookone about the greatest sitcom of all time! Also, thanks to the fine, always helpful editors at Applause, Marybeth Keating and Jessica Burr, who walked me through this multi-layered endeavor. I would also like to acknowledge the superb job of copy editors Lon and Debra Davis. They demonstrably improved the manuscript with their knowledge of the subject matter and attention to detail.

Special thanks are in order to my brother, Thomas Nigro, who accompanied me on a Seinfeld Reality Tour of our own, which began at Times Square and culminated at Toms Restaurant on Broadway and 112th Street. As we crisscrossed the city entirely on footin one afternoonhe snapped many fine photos of Seinfeld s New York. Thanks, too, to the incomparable Kenny Kramer for his contributions and the invitation to join him on his tour, which I look forward to in the future.

There are so many Seinfeld aficionados who shared with me their unique insight into the show and, in some instances, images from their personal collections. Many thanks to Joe Nigro, Remy Joseph DEsposito, Rosanne DEsposito, Ed Kallawasser, Patrick Downes, Stephen Spinosa, Peter Spadafino, Leon Hodes, Bill Hlubik, Ann Lynch, Sol Ives, Mike Red Lee, Gerald T. Mannion, Tony Trenga, Davis Herron, Norman Metter, The Contest expert Matt Laufer, Greg Vreeland, Disciplinarian Bill Cleary, Samuel Turk, Chris Winch, and, last but not least, John Roach, who thoroughly entertained me with his spot-on impersonations of Jerry, George, Kramer, andbelieve it or notElaine, too.

Part I

1

Postmodern Television

From Seinfeld s humble beginnings, co-creator Larry David insisted that the shows scripts be absent of any trace of pathos or sentimentality. No hugging and no learning on a Seinfeld set were likewise part of Davids unbending credo. Under no circumstances would Seinfeld characters become wiser, more thoughtful, and more compassionate human beings as the series progressed. They would not ever address the hot-button political issues of the dayat least not in any serious mannernor make some larger, socially invaluable contributions to the society at large. It is this curiously detached approach to the ways and means of situation comedy that immediately distinguished the show and set it apart from its predecessors both old and newer. No prior sitcom dared present to a television audience an ensemble of neurotic, self-centered, thirty-something characters with dubious moralsjerks, if you willwho, on top of all that, called Manhattans Upper West Side home.

As the 1970s dawned, America was still mired in an unpopular war in Southeast Asia; civil rights and womens rights movements were making conspicuous headway; and a spanking new environmental awareness assumed center stage as well. It was in this tumultuous snapshot in time that the American sitcom, too, underwent a comprehensive metamorphosis and suddenlyand without fair warningbegan to mirror the uneasy, conflicted, but always-animated social reality that ruled the day. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the American sitcom remained, by and large, true to its roots by steering clear of contentious societal issues. Sitcoms abiding missions were to be humorous distractions from the rough and tumble goings-on in the wider world. They were not conceived, nor written, with the intention of tackling the momentous issues making news, or the serious problems transpiring behind closed doors in American homes or on the streets of American neighborhoods.

Indeed, the first half of the 1970swhich was actually a continuation of the culturally sea-changing late 1960sbore witness to a rather comprehensive purge of old-style sitcoms and variety shows. Once immensely popular comic stalwarts like Jackie Gleason and Red Skelton, for example, disappeared altogether from the primetime lineup. Notoriously, CBS canceled en masse its rural-based shows, starting with Petticoat Junction (19631970). Pat Buttram, who played unctuous snake oil salesman Mr. Haney on Green Acres (19651971), complained that the network, in one fell swoop, cast asunder every show with a tree in it, including The Beverly Hillbillies (19621971), The Andy Griffith Show spin-off Mayberry R.F.D. (19681971), and My Three Sons (19601972). It little mattered that they were still holding their own in the ratings. Even the venerable Lucille Ball, whod starred in a sitcom virtually uninterrupted since 1951when Harry Truman was presidentcame across as a little too juvenile and silly for the socially conscious 1970s. Her last show, Heres Lucy (19681974), was the successor of I Love Lucy (19511957), The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour (19571960), and The Lucy Show (19621968).

Replacing the aforementioned shows and their ilk was mostly a new breed of sitcom that was seen as cutting edge and socially relevant. There were still exceptions like The Brady Bunch (19691974). Its exceptionalism, as it were, is precisely what drove its shows star, Robert Reed, to distraction. Nonetheless, even The Brady Bunch planted a pack of cigarettes in son Gregs jacket, which made for a lesson-packed episode.

The larger purpose behind the considerable change in content was to attract younger, more urban viewers and, of course, make important statements along the way. Sexual matters, for one, were no longer taboo on network television. When All in the Family debuted as a midseason replacement on CBS in January 1971with its lead character a working-class bigot with racial epithets aplenty on the tip of his tongueit was admittedly something of a culture shock. The 1970s sitcom formula outwardly insisted on characters who were groundbreakingat least as far as television was concernedin some evident way. The Mary Tyler Moore Show (19701977), for instance, revolved around the life and times of a single working woman on her own in the cold, cruel world of Minneapolis-St. Paul. This seemingly innocuous premise was, in fact, groundbreaking in 1970 when the show premiered. Mary Tyler Moore was no longer Laura Petrie from The Dick Van Dyke Show (19611966). Good Times (19741979) depicted a family living in a Chicago housing projectthe ghettowith all its inherent problems. M*A*S*H (19721983) was set in a Korean army hospital and married laughs with the horrors of war. Sitcoms of that era like Maude (19721978), One Day at a Time (19751984), and Alice (19761985) combined comedy with solemn life issues, such as abortion, drug abuse, and male chauvinism. Shows like Sanford and Son (19721977), Chico and the Man (19741978), and The Jeffersons (19751985) brought additional minority characters and, along with them, minority-specific issues to primetime audiences. Chico and the Man s Freddie Prinze was televisions first Chicano actor in a starring vehicle. And Redd Foxxs Fred Sanford and LaWanda Pages Aunt Esther werent averse to using the N-word on occasion. This sort of thing was, in fact, tolerated in the freer, less-afraid-of-words early and mid-1970s.