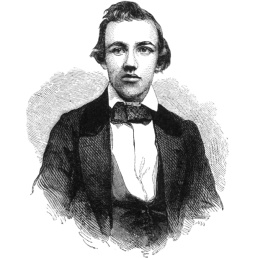

My System & Chess Praxis

Aron Nimzowitsch

My System & Chess Praxis

Translated by Robert Sherwood

New In Chess 2016

2016 New In Chess

Published by New In Chess, Alkmaar, The Netherlands

www.newinchess.com

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher.

Cover design: Volken Beck

Translation: Robert Sherwood

Supervisor: Peter Boel

Proofreading: Ren Olthof, Frank Erwich

Production: Anton Schermer

Have you found any errors in this book?

Please send your remarks to and implement them in a possible next edition.

ISBN: 978-90-5691-659-6

Translators Preface

It is a pleasure to help bring out this new, combined edition of Nimzowitsch. A fresh translation has been necessary for some time, and we can all be grateful to New In Chess for publishing it.

I have kept as closely as possible to the meaning and feel of the original German text. The serious reader is owed a faithful rendering of the mans thinking and attitude rather than the simplified and paraphrased versions that are sometimes preferred. This pays handsome dividends in a considerably deeper experience of the material and the man.

Nimzowitsch, for all his depth and his idiosyncratic way of writing, makes a conscious effort to be clear and helpful, and often exudes a human warmth toward the reader that the more technical and bloodless renderings of his work fail to convey. Nimzowitsch is an interesting guy. He is profound, emotionally sensitive to the point of an almost dangerous vulnerability, refuses to suffer fools gladly, despises provincialism and dogma, and feels it his mission to penetrate into the inner truth of chess out of a deeply felt respect for the authenticity of that truth. Nimzowitsch detests the superficiality and superciliousness of pseudo-professional thinking. His was a three-dimensional sensibility in a mostly two-dimensional world. In this he is situated squarely in the company of other early twentieth-century figures who also struggled to liberate us from the categorical judgments and smug self-satisfaction of much nineteenth-century thinking. Nimzowitsch himself is not without his inconsistencies, exaggerations, and occasional immature defensiveness, and one comes across errors from time to time. But, as the saying goes, the mistakes of great men are more venerable than the successes of lesser ones.

In making the translation I often referred to the version by Philip Hereford (1929). Herefords is for the most part a quite respectable rendering of Nimzowitsch; I certainly have admired his skill at unraveling some of the denser sentences. Its defect lies in its omission of certain passages that were evidently considered to be of questionable relevance or taste. In 1929 this was a defensible position; today we prefer our texts uncensored and authentic. The version before you is frank, unflinching, occasionally hard-edged, and at times marvelously soulful and warm. It is the real Nimzowitsch.

We have chosen to include Nimzowitschs The Blockade and his very interesting article On the History of the Chess Revolution 1911-1914. The Blockade is a two-part monograph originally published in Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten in 1925. Revolution provides essential background for understanding the inner currents of the Neo-Romantic movement. The latter article was already included as an appendix in the original German book Mein System. The Blockade was not included in either of the two books, and some of the games in this article later appeared in Mein System. We have decided to leave those games where they were again, this reflects our attempts to keep as close as possible to the original works.

Thanks are due to Jeremy Silman for the original impetus to produce an unvarnished Nimzowitsch suitable for the serious contemporary reader. Dale Brandreth at Caissa Editions provided the German texts. Allard Hoogland at New In Chess has handled the tasks of publication with his usual courtesy and skill. And Nimzowitsch deserves our gratitude for his insights and for his courage in holding his ground while the flak was coming in from all directions.

Bob Sherwood

Dummerston, Vermont, USA

May, 2016

My System

Foreword

As a rule I do not care for writing forewords. But in this case one would appear to be necessary, for the entire matter before us is so innovative and unprecedented that a foreword can only be a welcome mediator for the reader.

My new system did not come into being all of a sudden, but developed slowly and gradually; I might say it has been the result of an organic growth. It is true that the principal idea that of analysing the elements of chess strategy individually is based on inspiration. And yet of course it would by no means be sufficient for me to point out, about an open file, say, that one must take possession of it and make the most of it; or, concerning a passed pawn, that one has to stop it. No, the matter before us demands that we go into it in detail. It might almost sound comical, but I can assure you, my dear reader, that for me the passed pawn has a soul just as a human being does. It has wishes that slumber unrecognized within it and has fears of whose existence it hardly suspects. The same is true for the pawn chain and the other elements of chess strategy. I will give you a series of laws and rules for each of these elements that you will be able to apply, rules that I will go into in great detail and which will help clarify even the most seemingly arcane links between events that occur frequently on our beloved 64 squares.

Part II of the book discusses positional play, especially in its Neo-Romantic form. It is often said that I am the father of the Neo-Romantic school. So it will not be uninteresting to hear what I have to say on the subject.

Textbooks tend to be written in a dry and lifeless tone. It is believed we would be giving up something were we to let in a humorful turn of phrase, for what business would light-heartedness have in a textbook on chess! This is an outlook I cannot even begin to share. I will go further: I regard such a viewpoint as completely wrong. Real humor often contains more inner truth than the most earnest seriousness. For my part, I am a declared adherent of using comparisons with everyday life to comic effect. I am therefore ready to call upon the experiences of life to make comparisons so as to reach a clear understanding of the complex processes inherent in chess.

In many places I have provided a schema to make the mental edifice clear in a visible way. I took this step for pedagogical reasons as well as reasons of personal safety, for otherwise, mediocre critics there are such people would be able or willing to see only the individual details but not the wider ramifications of the conceptual framework that forms the real content of my book. The individual items, especially in the first part of the book, are seemingly very simple but that is precisely what is meritorious about them. Having reduced the chaos to a certain number of rules involving inter-connected causal relations, that is just what I think I may be proud of. How simple the five special cases in the play on the seventh and eighth ranks sound, but how difficult they were to educe from the chaos! Or the open files and even the pawn chain! Naturally each new part was more difficult to think through, as the book was organized in a progressive way. But this increasing difficulty I did not hold before me as, say, armor to protect myself against attacks from small-caliber critics. I emphasize this only for the sake of the reader. I will also be attacked for giving illustrative games played for the most part by myself. But such attacks, too, will hardly bowl me over. How could I not be justified in illustrating my system through my own games? Incidentally, I am in fact publishing a few (well-played) amateur games as well, so I am not all that self-indulgent.

Next page