Modern Ideas

in

Chess

by Richard Rti

21st Century Edition

Edited by Bruce Alberston

2009

Russell Enterprises, Inc.

Milford, CT USA

Modern Ideas in Chess

by Richard Rti

Copyright 2009

Bruce Alberston

ISBN: 978-1-888690-62-0

All Rights Reserved

No part of this book may be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

Published by:

Russell Enterprises, Inc.

P.O. Box 5460

Milford, CT 06460 USA

http://www.russell-enterprises.com

Cover design by Janel Lowrance

Printed in the United States of America

Table of Contents

Introduction

The 45 essays which constitute Modern Ideas in Chess appeared mostly in journals during 1921. Polishing was done the following year, and in 1923 the manuscript was published in English. The book was an instant success. Nobody had ever tackled chess in quite the way Rti had. For the first time ever, a very strong player provided a popular, readable account of chess ideas as developed by the leading players and handed down to generations following.

The chronology begins in the Romantic Era of Anderssen and Morphy, runs through the Classical School of Steinitz, Tarrasch, Lasker, picks up Rubinstein and Capablanca, and finishes off with Rti and his neo-romantic colleagues. Today we know this last group as the Hypermoderns, and Rti was certainly one of the ringleaders. In all, the book covers seventy years, 1852 to 1922.

Here the portraits of the great masters are vividly drawn and their most important theories carefully extracted and examined. Rtis explanations enable the reader to follow the development of chess ideas, of chess as art. Rti, as an artist himself, was interested in the creative process; he worked conscientiously to identify the tension that generates ideas. As a result, one can find here plenty of solid chess instruction, almost as a by-product of Rtis interest in the growth of chess.

And there were plenty of new chess ideas still to be discovered in the years following the First World War. So many, in fact, that when the Hypermoderns burst on the scene in the early 1920s it appeared that a revolution in chess thinking was taking place. It was a heady time and Modern Ideas conveys the excitement of the period.

The three periods Romantic, Classical and Hypermodern formed the foundation for the subsequent growth of chess and the development of new ideas. Perhaps the discoveries have not been as dramatic as those of the 1920s, but the continual influx of creative masters, even today, confirms Retis basic thesis.

For the present reworking the editor has converted the text to double column, figurine algebraic notation, and added diagrams. Editorial touches include slight additions, one deletion, and a handful of minor corrections. This is Rtis book and it should come through pretty much intact.

Bruce Alberston

Astoria, New York

November 2009

Authors Preface

If we compare the games of chess of recent years with the older ones, we shall find, even with a superficial consideration of the games handed down to us from olden times, absolutely different openings and unusual contours of positions. New ideas rule the game and have considerable similarity with the ideas of modern art.

As art has turned aside from naturalism, so the ideal of the modern chess master is no longer what was called sound play or development in accordance with nature. That is to say in accordance with nature in the most literal sense; for that old kind of development was directly copied from nature.

We believe today that in the execution of human ideas deeper possibilities lie hidden than in the works of nature: or to put it more accurately, that at least for mankind the human mind is of all things the greatest that nature has provided. We are, therefore, not willing to imitate nature and want to imbue our own ideas with actuality.

Those pioneers in art, who are difficult to understand, are acknowledged by the few and jeered at by the many: Chess is a domain in which criticism has not so much influence as in art; for in the domain of chess the results of games decide, ultimately and finally.

On that account Modern Ideas in Chess will perhaps be of interest for a more extended circle. The artists who, in spite of derision and enmities, follow their own ideas, instead of imitating nature, may in times of doubt, from which no creative man is free, know, and cherish hope therefrom, that in the narrow domain of chess these new ideas in a struggle with the old ones are proving victorious.

I have in this volume attempted to indicate the road along which chess has traveled; from the classicism of Anderssen, by way of the naturalism of the Steinitz school, to the individualistic ideas of the most modern masters.

Richard Rti

Foreword

Richard Rti was inspired to write this book, as he indicated in his original Foreword, because of his admiration for the younger generation of his day. But Rti was more than inspired. He felt provoked by a member of the older generation.

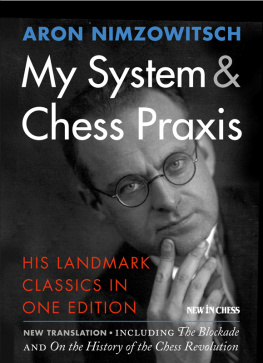

Franz Gutmayer, a German author 32 years Rtis senior, wrote many popular books that gave the impression Gutmayer was a master (he wasnt) and he had unraveled the mysteries of the game (he didnt). Among his works was The Way to Chess Mastership, The Secrets of Art of Combination and even one titled My System.

Richard Rti, on the other hand, was a legitimate star. He lost some of his best playing years from when he was 25 to 29 due to World War I. The war also prevented him from completing work on his doctorate in mathematics. Nevertheless, at age 33 when this book appeared Rti was still among the worlds half dozen top players and one of the two or three most original. After their sparkling game at Vienna 1922, Alexander Alekhine said Rti was the only opponent whose moves surprised him. Rti was also an accomplished endgame composer and blindfold player. He had just published, in 1921, what became the most famous king-and-pawn study in history.

You might think that as one of the true princes of the game, Rti would pay no attention to a chess Philistine. But what galled him was that this Gutmayer claimed he was creating the definitive books on the stylistic history of chess. He was trying to write a kind of Gutmayers Great Predecessors.

Rti took aim at his target in his newspaper column. His trashing of Gutmayer, as well as criticism of the Immortal Game, led him to tackle other controversial themes and more profound questions. He eventually collected his thoughts in a 121-page book, which appeared in 1922 as Die Neuen Ideen im Schachspiel (New Ideas in Chess).

It was the first time that a great author had analyzed how the game of chess had evolved. Some of the chapters such as An Old Question and A Complicated Position are stunning in their simplicity of presentation and yet depth of insight. But so many of Rtis perceptions have been repeated and recycled by his imitators that they seem trite today.

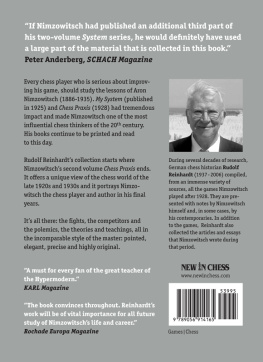

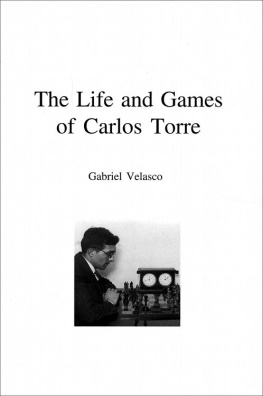

For example, Rti was well ahead of the curve when he called Paul Morphy the first positional player. He was perceptive, too, when he noted how Jos Capablanca regarded every move that was not demanded by a plan to be a waste of time. And it was Rti who detected how Alekhine beats his opponents by analyzing simple and apparently harmless sequences of moves in search of a surprisingly strong move at the end of a variation. (In contrast, Garry Kasparovs My Great Predecessors series had tons of new analysis but very few original insights.)