Page List

ETCHING

an artists guide

ETCHING

an artists guide

Ann Norfield

First published in 2019 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

Ann Norfield 2019

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 616 6

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank all the contributing artists for giving their time and for creating such fantastic prints. Also to Cora James for her beautiful photography.

A big thank you to friends and colleagues at East London Printmakers for their patience with the book and for helping to make the studio such a great place to work. Special thanks to Steve Edwards for his kind willingness to take on-the-spot photos.

Huge thanks to Lucy, Alice and the many friends who gave continued encouragement. Also to my parents for their understanding.

Biggest thanks of all to Michael Taylor for his support, fortitude and practical help whenever they were most needed.

INTRODUCTION

Artists have been using the printed multiple image as part of their practice for over 500 years. Materials, processes and techniques may have developed over time from the simplest woodcut through to the latest digital technology, but artists have always been, and will continue to be, intrigued and challenged by each and every new technological development within print that comes along. Those that we now see as traditional were themselves once new and revolutionary, and of course those that we now see as new and revolutionary will soon become part of the tradition.

Etching has developed over this period from a simple decorative craft to a fully expressive art form, one that continues to use its history and traditions to reveal our contemporary world with fresh eyes. When we visit any gallery or museum we still see work that uses the exact same materials and techniques that Rembrandt and Drer would recognize, but we can also see work produced with very new materials, using the most recent technologies and processes available. The great strength of printmaking in general is that it can draw on a rich and vibrant past while continuing to be relevant to the present.

In many ways, the making of an etching can be seen as a destructive and corrosive process. The acids and tools that we use are to bite, gouge and deface the surface of a smooth metal plate. Yet they produce images of such delicate beauty as Picassos Dove as well as the brutal revelations of Goyas Disasters of War.

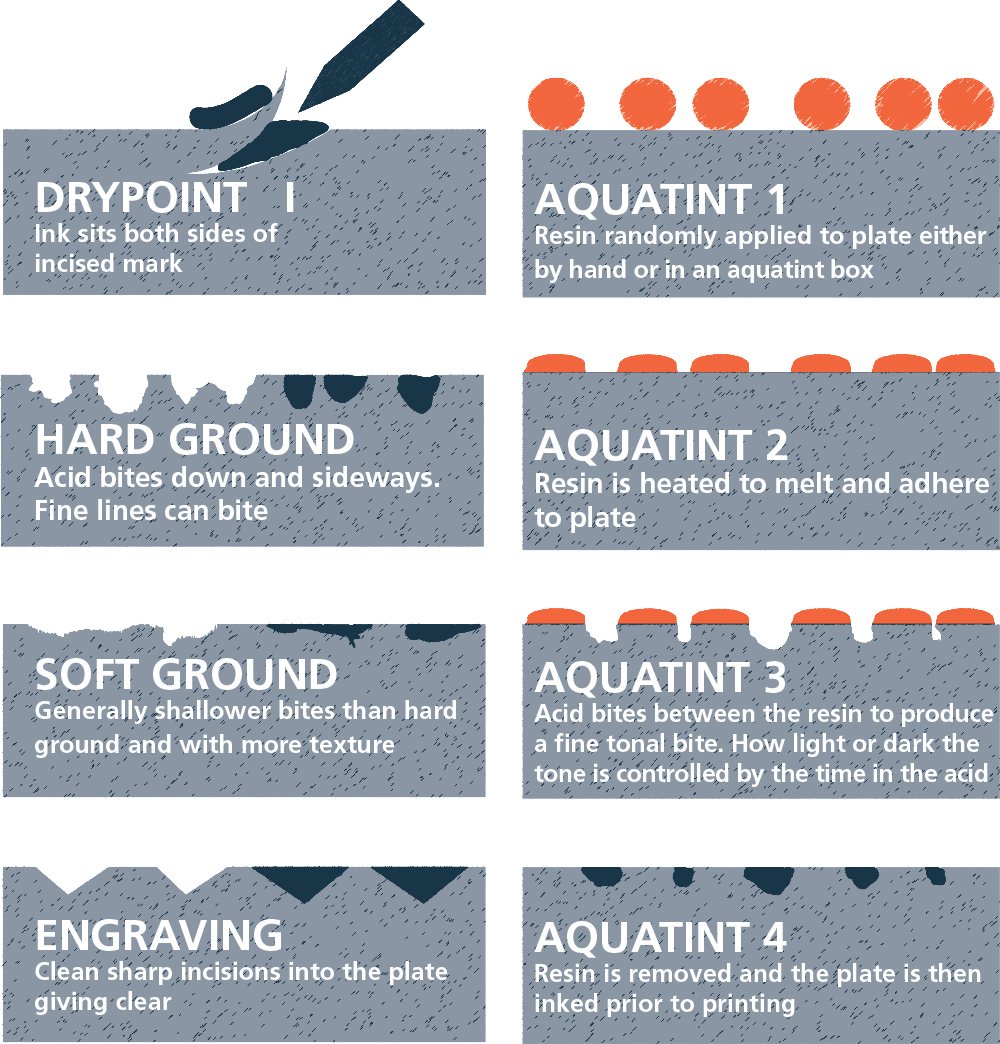

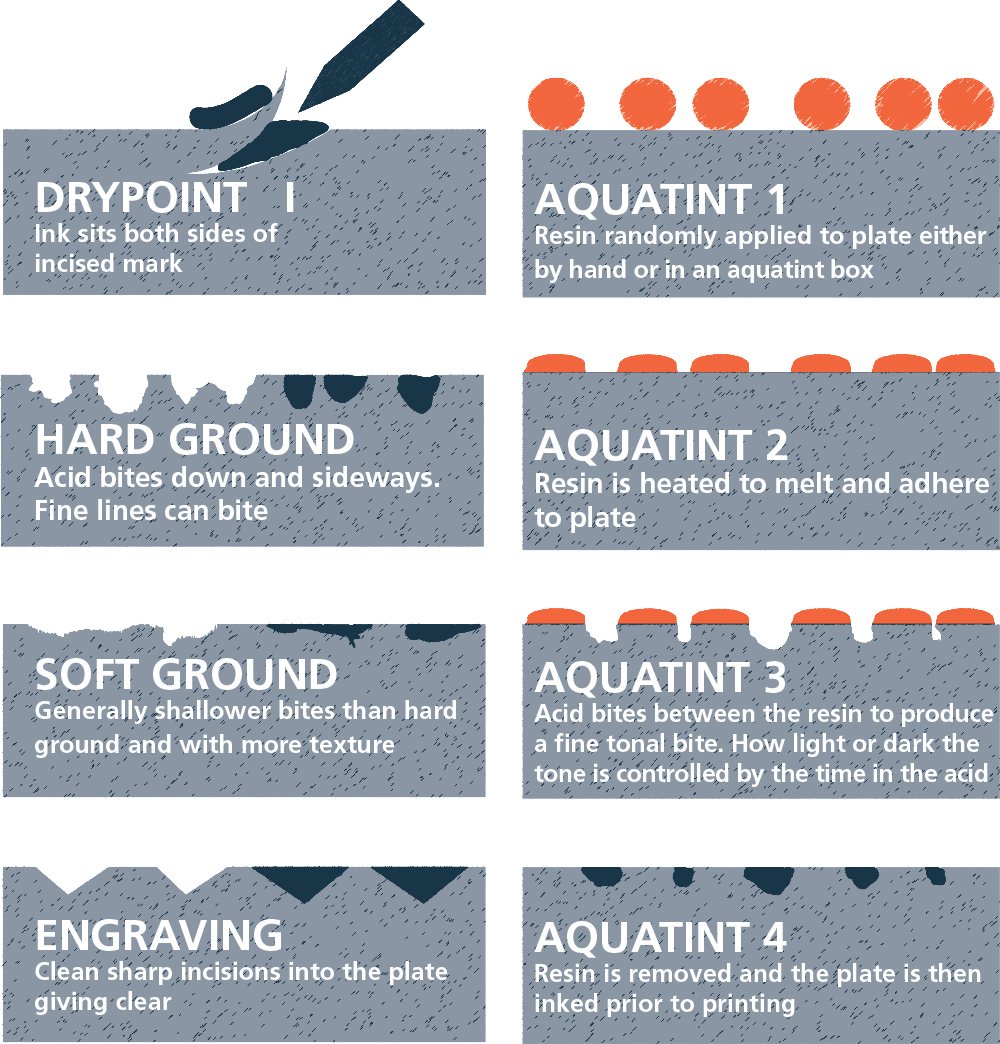

The starting point to any etching is quite often one of the three traditional processes of hard ground (the drawing of sharp lines through a wax and bitumen layer), soft ground (the drawing of gentler, tonal marks through a wax and tallow layer) and aquatint (the painting of washes of light and dark tones over areas of the plate using a fine resin dust as an acid resist).

The etched or incised plate can then be printed one at a time in black ink, or with multiple plates and in any number of colours. With the more recent developments of photo-etching and polymer gravure, the photographic and digital image can also be the starting point of the creative process, or may be incorporated within the more traditional mark-making techniques.

History

The art of etching is generally thought to have started with the rubbing of dark waxes into engraved and incised armour to further highlight their decoration. In order to record their designs for future replication, armourers developed ways of impressing these marks/incisions into soft absorbent material, which could hold the image separately from the metal plate into which it was engraved. A printed record was made and over time it is not difficult to see how this means of replicating an image was found to have such profound artistic possibilities.

The development of each new print technology or material has always created new possibilities for the artist. It is rare that any new development was at the instigation of the artist or was first thought of for strictly artistic expression. On the whole it is a more prosaic commercial need that initially drives print technology forward. Artists will find a use for almost anything new that comes along and simply add it to the lexicon of visual languages they already possess and that have been developed over the previous centuries. Good techniques, like good ideas, do not simply disappear after use; instead they can be added to, and new uses found for them.

The rise of the digital image and its appearance within the broad palette of visual languages available to an artist is just the latest development in the long technical history of print.

Back in the fifteenth century most people in Europe were still illiterate and visual imagery was crucial to the communication of both new ideas and those of longstanding tradition. One of the most important technological advancements of the last millennium, namely Gutenbergs invention of the printing press and its use of movable type, meant that the sharing and dissemination of new ideas was more possible and also much faster. The idea that imagery could be replicated through mechanical means was to have a profound social and political effect across all social strata. No longer was it only the literate and privileged few who were able to access fresh ideas and express opinions. The printed image helped to illuminate this new world as the printed word helped explain it. The democratization of Western Europe came about as much through the use of the democratic art of print as any other.

This relationship between artistic expression and technology can be seen running all the way through the development of printmaking as a whole. As the engraved print became the dominant means by which artists circulated their work to a wider audience, it became both a means of artistic expression and a commercial necessity. More copies of any image to sell, at more affordable prices, meant a growing audience for the artists work. In turn this created more income and, more importantly for the artist, paid for the time and means to make new work.