IMAGES

of America

AFRICAN AMERICANS

OF TAMPA

The Burgert Brothers were commercial photographers whom this author and the entire Hillsborough County community have to thank for preserving a half century of local history. (Courtesy of the Tampa Hillsborough County Public Library.)

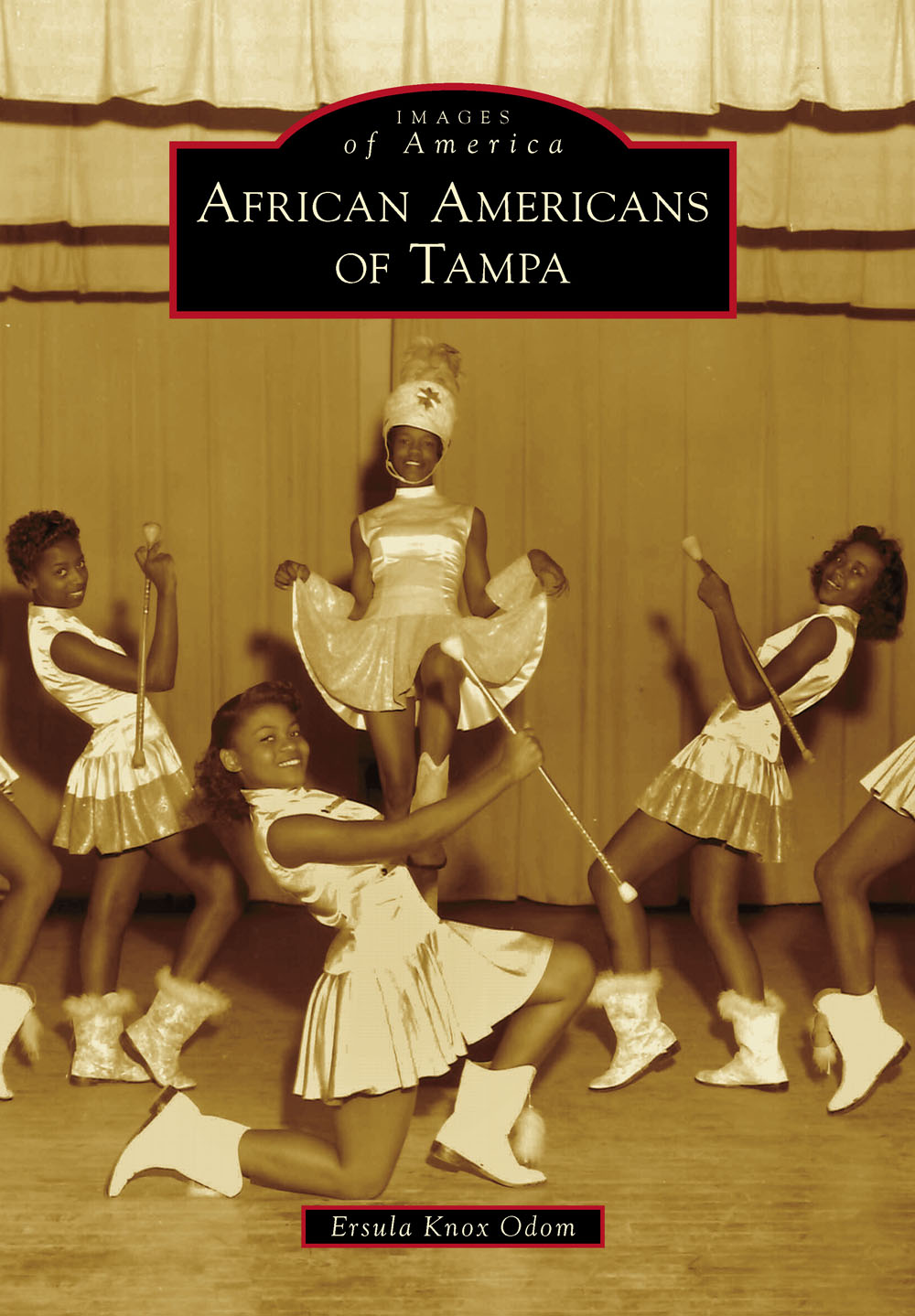

ON THE COVER: Majorettes were a standard and valued section of the typical marching band. Swirling, spinning, and synchronized baton maneuvers were required skills for these young ladies of Middleton High School. Their beautiful smiles, seen here as they pose on October 11, 1954, made them a wonderful example of an era that needs to be remembered. (Courtesy of the Tampa Hillsborough County Public Library.)

IMAGES

of America

AFRICAN AMERICANS

OF TAMPA

Ersula Knox Odom

Copyright 2014 by Ersula Knox Odom

ISBN 978-1-4671-1274-1

Ebook ISBN 9781439648575

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014936972

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

This book is dedicated to those who shared their connections and asked, Did you talk to... ? and then picked up their telephones and called that person. It is also dedicated to those persons who allowed the author in and walked down memory lane with her, especially the late attorney Frank S. Stewart.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to give a heartfelt thank-you to the Hillsborough County Public Library staff, especially those employees of the John Germany Genealogy Department. Their assistance with my enthusiastic search of the Burgert Brothers photography collection is most appreciated.

A special thanks to the Tampa Bay Black Heritage Festival, Richedean Hills-Ackbar, Frank S. Stewart, Doris Ross Reddick, Dr. Walter L. Smith, Ethel Johnson of the Weekly Challenger News, Coach Billy and Dorothye Reed, Delano S. Stewart, Tanya Akbar, Myron Jackson, Hewitt Smith and Mrs. Kennedy, Dianne Speights, Fred Hearns, the Tampa chapter of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society, Warren H. Dawson, the Florida Memorial Carrie Meeks History Museum on the Florida A&M University campus, George Robinson, Richard Robinson, Phyllis McEwen, Osborne Odom, Elaine Harris, the Reynolds family, Michael McNeal, Justine Anderson, Sen. Arthenia Joyner, and Harold Clark.

Throughout this book, certain images will be followed by the following credits: Tampa Hillsborough County Public Library (HCPL) or University of South Florida Special Collections (USF).

INTRODUCTION

Tampas African American history began with names that may never be known. What is known is that there were many who came to Tampa to escape slavery. Some joined and lived with Native Americans. Many arrived in Tampa as Cubans. Some arrived as free men and women. Some were enslaved. Many arrived as soldiers armed and ready to fight for and defend freedom. This book preserves some of the names, faces, places, and events and begins to fill some missing pieces.

Indians and African Americans were united by a common enemy. The enemy wanted to take one groups land and the other groups freedom, and this fostered a natural alliance between the two. This alliance is mostly documented in the history of the Seminole Wars.

Tampas history from 1860 through 1881 is what the author considers the silent years because a great deal of what happened for African Americans in Tampa during that time still does not have a strong voice in history. The Civil War, emancipation, and Reconstruction occurred during these years.

In June 1862, during the Civil War, when incorporated Tampa was just seven years old, Union gunboats arrived at Fort Brooke, and those on guard refused to surrender to the Federal commander. A second attempt to capture Tampa occurred on October 17, 1863. Two ships arrived on a mission to stop the blockade-running operations of Capt. James McKay. Two McKay vessels loaded with cotton and ready for export were burned. Confederates caught up with the Yankees at Ballast Point. Nine people were killed and many more injured. There was no clear victory. The adage that there are two sides to every story rings true when one considers the plaque commemorating the cannons last stand. A portion of it reads, These 24 pound shot size cannon were part of a battery of three placed in Fort Brooke during the War Between the States. They and two 6 pound shot size rifled cannon successfully defended Tampa until May 5, 1864. On that date, federal troops, composed of elements of the 2nd US Colored Regiment, the 2nd Florida Calvary, and the US Navy, captured the town and fort by surprise. The 24 pounders were disabled by breaking off a trunnion and destroying their barbette carriages. The 6 pounders were then taken to Key West. Fort Brooke surrendered without a single shot. The fort was destroyed, and the cannons were thrown in the bay. To some, May 5, 1864, was the last day the cannons defended Tampa. To African Americans, May 6, 1864, represents the first day of freedom, even if was not known. The fact that a colored regiment was involved is hidden in plain sight behind the title The Spanish Fort. The Friends of Plant Park must be celebrated for including this history in 2008.

As for African Americans role in the Spanish-American War, consider that on July 1, 1898, four colored regiments, along with Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders, were a part of a 15,000-troop deployment to Cuba. When the United States began their evacuation, they kept the African American Ninth Infantry Regiment in Cuba to support the occupation. The rationale for this was because of their race, and because of the fact that many African American volunteers were from Southern states, meaning they would be immune to yellow fever. They were not immune.

Whether they were employed by others or functioned as business owners, African Americans were a part of the very foundation upon which Tampa was built. It was by their hands and their sweat that Tampa emerged from a swamp into the home of world-renowned citrus, shipping, fishing, and cigar industries.

In 1881, Henry B. Plant brought the railroad to Tampa, uniting water travel and shipping with land travel and freight. Tampa exploded, and the role of African Americans with it. According to the March 30, 1926, Tampa Morning News, Tampas population grew from 94,743 in 1925 to 213,615 in 1930. Even though the role of African Americans was critical, Jim Crow laws suppressed and silenced cross-cultural celebration of this importance; however, celebration happened in the African American community. Success happened. This book is a glimpse into the world as it was primarily before desegregation. Central Avenues business and social area, the Urban League, unions, mens and womens clubs, fraternities and sororities, schools, and churches were at the core of this success, and they are the subjects of this book.

One fascinating example of how one person can create an industry and change a citys destiny is that of Dr. Odet Philippi. He purchased a black woman who was a highly skilled cigar maker and brought her to Tampa, where she made cigars for his salon patrons. She made the first cigars in the area, which came to be known as the Cigar City.

Next page