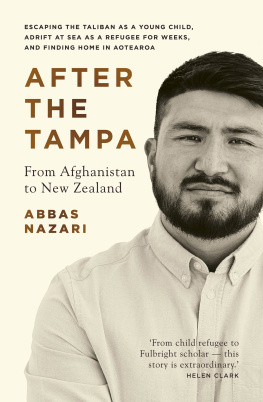

First published in 2021

Copyright Abbas Nazari, 2021

Images authors private collection unless otherwise credited on page.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Allen & Unwin

Level 2, 10 College Hill

Auckland 1011, New Zealand

Phone(64 9) 377 3800

Email

Webwww.allenandunwin.co.nz

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065, Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand

ISBN 978 1 98854 764 0

eISBN 978 1 76106 232 2

Design by Megan van Staden

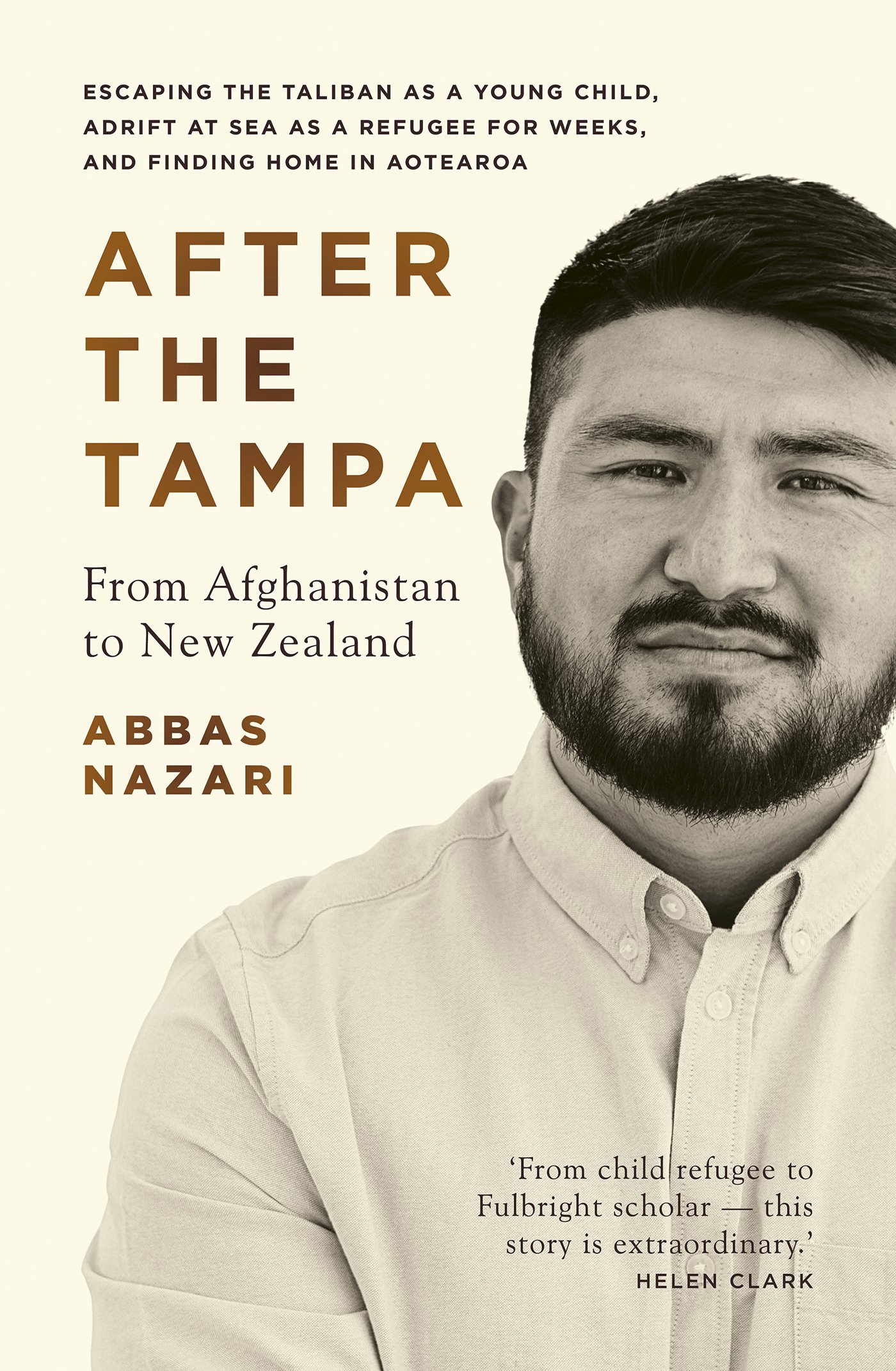

Cover photo by Juan Zarama Perini

To Mum and Dad

Thank you for giving up your today for our tomorrow.

OUT BEYOND IDEAS OF WRONGDOING AND RIGHTDOING, THERE IS A FIELD. ILL MEET YOU THERE.

RUMI

I WILL BE the first to admit I have not personally accomplished anything worthy of writing a book about. I have not built a billion-dollar company, or won an Olympic gold medal, or summitted some great mountain. In fact the most interesting thing Ive done is receive a scholarship to an American university. So when I was asked to write a book about my life I felt like a fraud.

What story would I tell?

Would anyone be remotely interested in what I had to say?

But as I thought about it more, I realised there was a story I could tell. A story that deserves to be chronicled. So this book is not about the life and times of Abbas Nazari. It has my name on the cover, but the story belongs to all of the 433 asylum seekers who were rescued from drowning in the Indian Ocean by the Norwegian container ship, the Tampa.

Twenty years on from those harrowing events this story is more relevant than ever. As the worlds refugee crisis deepens, no one can ignore the plight of the thousands of desperate people fleeing their various war-torn homelands.

At events where I am asked to speak, I am astounded by the feedback I receive when I talk about this. Everyone has heard about refugees, but hardly anyone has ever met or got to know one personally. Its time they did.

I am Abbas Nazari. My family and I arrived in New Zealand as refugees rescued by the Tampa. I am proud to call myself a New Zealander.

Afghans are notoriously bad at writing things down, so I hope this book serves as a memoir of all the people who fled with us. Much of the detail comes from my childhood memory. For details of events during which I was not present or cannot recall clearly, I have relied on the memories of others present, such as my parents and other Tampa rescuees who were eventually resettled in New Zealand.

I am fortunate to be in a position where I can write a book about my journey. For the majority of refugees it is a very different story. This book is theirs too. It begins in Afghanistan but it could just as easily be Somalia, Syria, Nicaragua, Myanmar or any of the other conflict zones around the world.

It is the story of every refugee who has been desperate enough to pack up everything, leave home and friends, and set off into an unknown future. I hope that as you read it you are prompted to think about their plight.

The topic of refugees and asylum seekers provokes heated debate and passionate responses from people, but few who are party to such discussions have actually lived the refugee experience. Few know what it is like to uproot yourselves from your homeland, risk everything, then, if you are exceptionally lucky, be resettled in an utterly foreign land, learning to navigate a new hyphenated identity. What is that experience like? Do they ever hanker to return home?

I hope this book helps in some small way to shed light on a global issue facing humanity.

WAKE UP! ABBAS, wake up we have to go now! hissed Mum as she shook me. Get your things the bus is here. Hurry!

It was the middle of the night. I wiped my eyes and sprang to my feet. All around me my siblings and the other children were a swirling hurricane of activity in the dormitory. I reached for the one thing I could call mine, the small navy backpack Dad had bought me for school in Quetta. I folded the donated T-shirt and pants Mum had placed on my pillow and stuffed them inside. I was seven years old, and a few months after leaving Afghanistan my worldly possessions amounted to a backpack and two items of clothing. Fearing this would never be enough for whatever lay ahead I filled the empty space with anything I could lay my hands on. Some rubber bands. A fork. Two bananas. A pen. A plastic bag. A pair of socks.

As I did up my Velcro sandals I peered out the window into the dark and could make out a small bus parked to the side of the main gate to the dormitories. A grizzled man with his belly hanging out of his shirt stood by the bus door, counting people as they boarded. A wiry figure was helping load the bags. They were sweating, with dark circles under their eyes as if they hadnt slept for weeks. They didnt look at all friendly.

Hurry or there wont be any seats left for us, said Mum, urging me down the stairs.

Dad helped load luggage into the undercarriage while Mum whispered a prayer. My baby brother Mojtaba was wrapped tightly in a blanket under her arm, while her other hand held my sister Shekufahs. Big brothers Ali and Sakhi were looking around hopefully for their friends. Surrounded by my family, I was not frightened, just excited that we were finally getting out of this horrible place.

The curtains on the bus were all closed. Once everybody was on board the engine roared to life, the headlights turned on and we were on our way. I fell asleep almost immediately as the bus glided silently through the city streets.

Some hours later I was jolted awake for the second time that night. The city lights had been replaced by a thick jungle of coconut palms on either side. The smooth asphalt had given way to a bumpy dirt road. As the bus rattled along a few people started vomiting. A sign of things to come.

Quiet! hissed the wiry man. Nearly there. He put his fingers to his lips.

We drove a little further down the dirt road until we reached a clearing. The unmistakable sound of crashing waves told us we were at the coast, but the night was so dark I couldnt see where land ended and the sea began.

The bus stopped and the wiry man got up, clutching a fat yellow envelope. He put his finger to his lips again, gesturing to us to remain quiet, then disappeared into the jungle. After a few moments he returned, minus the envelope. The driver restarted the engine and began to move again.

Silence hung in the humid tropical night. As we drove on, the jungle thinned, then receded completely on one side, revealing a black canvas. The ocean. We were in a clearing near the edge of a cliff about 30 metres above the sea. The bus drew closer to the cliff edge, so its headlights illuminated the waters below. A wooden fishing boat, perhaps twice as big as our bus, was tied to a rock with thick ropes. It rose on every wave, scraping the rocks and tautening the ropes with every push and pull.

Surely this was not our ship. There must have been a mistake.

Next page