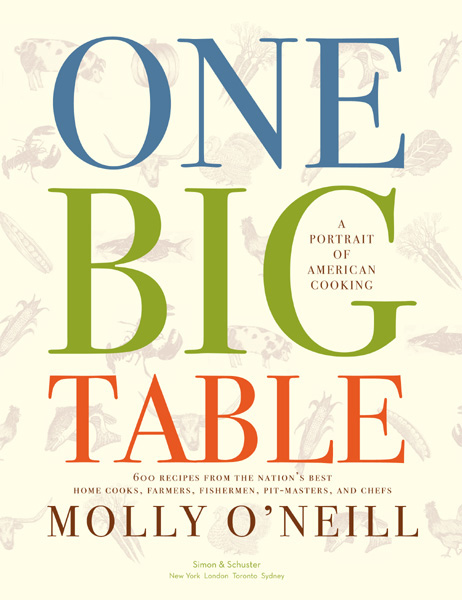

ALSO BY MOLLY ONEILL

Mostly True: A Memoir of Family, Food, and Baseball

New York Cookbook: From Pelham Bay to Park Avenue, Firehouses to Four-Star Restaurants

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2010 by Molly ONeill

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition November 2010

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or business@simonandschuster.com.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com .

Designed by Joel Avirom and Jason Snyder

Images edited by Rebecca Busselle

Permissions and acknowledgments appear on page 862.

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ONeill, Molly.

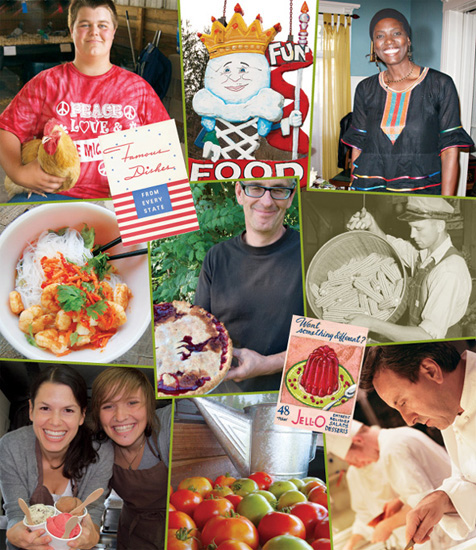

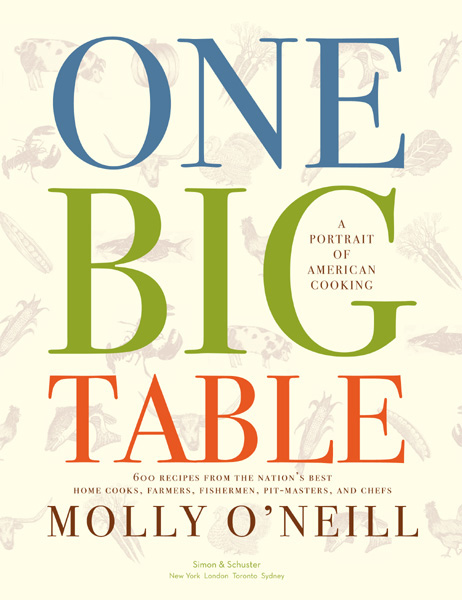

One big table : A portrait of American cooking : 600 recipes from the nations best home cooks, farmers, fishermen, pit-masters, and chefs / by Molly ONeill.

p. cm.

1. CookingUnited States. I. Title.

TX907.2.O54 2010

641.50973dc22 2010028841

ISBN 978-0-7432-3270-8

ISBN 987-1-4516-0977-6 (ebook)

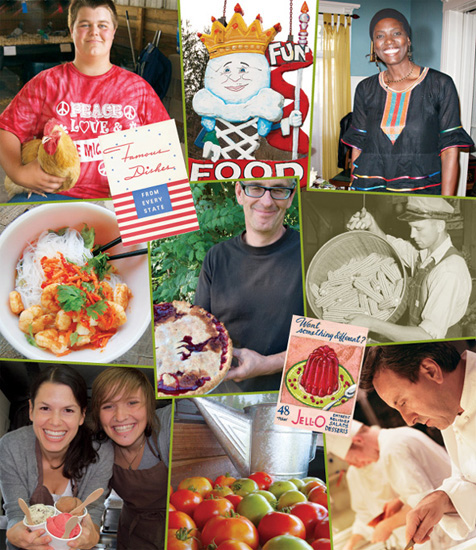

For Rebecca Busselle, photographer, writer, cook, colleague, fellow traveler, and friend, with gratitude as large as the America we discovered, mile by mile, dish by dish, story by story.

BAD DINNERS GO HAND IN HAND WITH TOTAL DEPRAVITY, WHILE A WELL-FED MAN IS ALREADY HALF SAVED.

The New Kentucky Home Cook Book, 1884

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

Nibbles, Noshes, and Tasty Little Plates

CHAPTER 2

Pickles, Salsas, and Other Condiments, Savory and Sweet

CHAPTER 3

Steaming Bowls: Soups, Chowders, and Other Consolations

CHAPTER 4

Conspicuous Consumption of Cellulose: Salads

CHAPTER 5

From Sea to Shining Sea: Fish and Shellfish

CHAPTER 6

Poultry in Every Pot, Oven, Broiler, and Grill

CHAPTER 7

Everything but the Squeal: Beef, Buffalo, Game, Lamb, and Pork

CHAPTER 8

Eat Your Vegetables

CHAPTER 9

Amber Waves of Grain

CHAPTER 10

The Sweet Life

INTRODUCTION

HOMETOWN APPETITES

F or many years I lived in a Hells Kitchen loft, and from its windows I could see a patch of the Hudson River. I liked knowing that the water was there, keeping the place that Id chosen to live, New York City, safely apart from Ohio, the place Id left behind. But for about fifteen years, I forgot to look out the window. I was a restaurant critic and I was eating, drinking, inhaling the city, writing books and stories, living the life that Id imagined when I was growing up in Columbus.

But in the mid-1990s, I began to stare at the river. Work was great, life was good, but there I was, staring at its far shore in the direction Id come from. I did not imagine any connection between my reveries and my sudden mania for transforming my terrace into a small farm. To my mind, the container garden was an early expression of locavorism. After the garden, a dog moved in with the boyfriend. And as far as I was concerned, these creatures and cultivars accounted for my otherwise inexplicable enthusiasm to follow the river north to find a weekend house.

I had no trouble explaining to myself the difference between my city and country cooking. My Manhattan kitchen was not all that different from the restaurants where Id worked: I imagined a dish, I ordered the ingredientset voil!: Centerfold Cuisine. But there was no such cornucopia ninety miles up the river from Manhattan. The availability, not imagination, determined dinner. The best produce that the local farms had to offer was sold in the city; what was left required long, slow, homey cooking to coax out its flavor.

Nevertheless, at Manhattans restaurants, at dinner parties and charity events, my colleagues and other members of the food cognoscenti began to talk about the end of American home cooking. The argument was that the more people spend on their kitchen range, the less likely they are to cook on the thing and that the fastest-growing department in grocery stores was the prepared foods. One survey found that an increasing number of Americans tuned in to the Food Network on their kitchen TVs so theyd have someone cooking. In New York City, dinner had long meant eating out, or getting take-out, which was no longer my experience. But I refused to believe that this philosophy had crossed the Hudson and infiltrated the mainland.

To reassure myself, I called each of my five brothers in Ohio. Our conversations were less than comforting.

How many times a week do you cook dinner at home? I asked.

How are you defining cooking? one answered warily.

I was soon reading reports that somewhere between supersizing and the current romance of farmers markets, Americans had stopped cooking. The possibility that the results might be true gave me a sense of urgency about finding true American cooking.

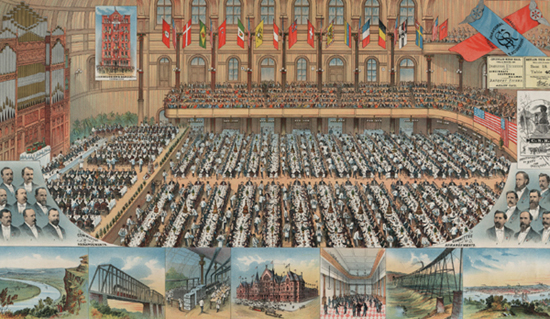

My weekends upstate began to stretch to four days. I cooked more, ate out less, spent days lurking on food sites chatting with people about what they cooked and why. A wall of my study was soon covered with historic maps of the United States: the Armour Companys Food Source Map (The Greatness of the United States is founded on Agriculture), the hog-shaped Porcineograph, and Miguel Covarrubiass Map of Good Eating were soon joined by contemporary examples like Gary Nabhans Regional Map of North Americas Place-Based Food Traditions, the National Golden Arches Locator, and Kentfields America Eats Organic Coast to Coast. I spent a year reading American food writing and constructing maps of my ownwhat was grown, what was eaten, when, why, and by whom.

Next page