Contents

Guide

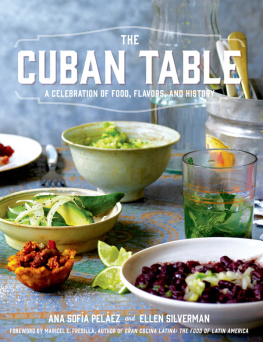

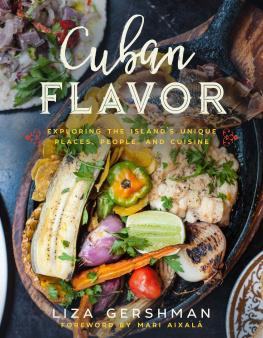

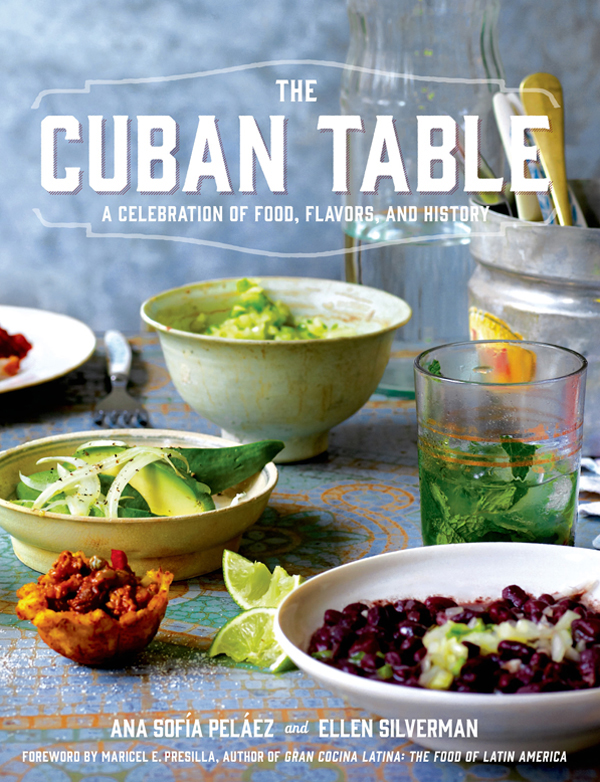

THE CUBAN TABLE

A Celebration of Food, Flavors, and History

ANA SOFA PELEZ

Photographs by

ELLEN SILVERMAN

ST. MARTINS PRESS

NEW YORK

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To my grandparents, who had to leave it all so I could have it all.

A.S.P.

For my dear husband Josh and son Luca, who are my best dining partners. And to all of our family and friends who regularly gather around our table to share food and conversation.

E.S.

Our Cuban Tables

FOREWORD BY MARICEL E. PRESILLA

Culinary historian, James Beard Award Winner, chef of Zafra and Cucharamama in Hoboken, NJ, and author of Gran Cocina Latina: The Food of Latin America (W. W. Norton, 2012)

A QUIET CLARITY SUFFUSES THE PAGES OF THIS BOOK, AND AN INEXORABLE TRUTH is told on every page: There is no single Cuban table, but many, straddling the Florida Straits, scattered across the globe, and built on memory fragments of what once was when we were all one people, living together on a crocodile-shaped Caribbean island.

Wherever Cubans have found homes outside the island, we have planted roots firmly in the here and now, for we are a pragmatic people. Nonetheless, we yearn for the Cuba of our imaginationsthough no two Cuban exiles can agree on what this means. Nor can we find the essence of Cuban cooking by looking at only one side of the divide, but rather by putting together the pieces of the scattered puzzle we have become since the Castro revolution in 1959.

I left Cuba for the United States in 1970, but I lived my formative years in Santiago de Cuba in a family of artists, intellectuals, and gifted cooks. My Cuban table was bountiful and diverse, steeped in the culinary traditions of eastern Cuba. My maternal aunts were careful and sophisticated cooks, lovers of fine china and embroidered linen tablecloths. They were also fearless Amazons of the kitchen with an uncompromising farm-to-table sensibility and a reverence for fresh produce, home-raised poultry, and local fish and game caught by my uncle Oscar. My paternal grandmother, Pascuala Ferrer, was born on a cacao farm in Jauco, near Baracoa, Cubas first Spanish city. She was a true country cook, gutsy and earthy, reveling in big soups like ajiaco, brimming with tubers and starchy vegetables and flavored with farm-smoked pork. As a bride in the small town of Baire, she had learned to cook traditional dishes from the central part of our region that were rarely seen elsewhere in Cubadishes that my father, Ismael Espinosa, craved and re-created in his Miami kitchen to his dying day.

I was lucky to experience these two worlds firsthand on the island, and they are the foundation of the Cuban table I have re-created in my U.S. homeneither wholly urban nor fully country, but a blend of the two. My cooking experience does not mirror that of Ana Sofa Pelez, who was born in the United States of Cuban parents, nor even that of members of my own family who have come here in more recent years. Each of us is shaped by our intimate connection to the cooking of our families and regions, but also by the moment of our departure, or that of our parents or grandparents.

I still think of the island as a cradle of comfort and lushness. I have thrown beans into the ground and seen them grow. I have stretched out my hand and picked delicious mango and papaya. In deep green forests and tall mountains rimming the horizon a dark blue, I have heard the gentle rustling of animals and the chirping of birds. I have ambled down Cuban roads, and seen people at ease with themselves, moving with a relaxed flow, their faces friendly, their manner open and hospitable. Though I could see the dignified Spaniard in their bearing, I could also see an African rhythm in their walk. I have heard the distinctive sounds of our hybrid culture: conga drumming during carnival, fresh red snapper sizzling in an iron pan, the dcimas (country ballads) of the Cuban guajiro (peasant) strummed on a guitar as a pig roasted on a spit. I have sat at many Cuban tables, bitten into casabe (yuca bread), sipped a spoonful of ajiaco, and gotten a hint of the cooking of the Tanos (Arawak) who lived in these islands before the Spanish came.

In my memory, this is as close as I have gotten to paradise. Not even the hardships of war during the Cuban revolution could strip this world of its wonder, but decades of deprivation and repression after 1959 took their toll. We experienced the indignities of life on ration cards, enduring long lines to buy bare essentials and often felt hungry. Many who stayed saw their families divided, their pantries empty, the flavors of cherished family recipes compromised for lack of key ingredients, and the richness of their tables dulled by chronic shortages of staples from beef and fish to rice and beans, from cherished cooking fats like olive oil to raisins and olives. Even the memory of dishes that were once at the core of our identity faded into a twilight zone of sorts, waiting to be rescued as families separated and older cooks began to die.

The Cubans who left the island in waves beginning in 1959 and who came to the United States, first legally in chartered planes and later illegally by boat or flimsy raft, worked hard to reinvent themselves through food. They represented every region of the island, every race and occupation, from blue-collar workers to professionals, from fishermen and farmers to landed aristocracy. No longer segregated by class, color, or geography, we were brought together through the common experience of exile and, penniless, we learned from each other in ways that were not possible when we lived together on the island. Our Cubanness and our desire to build new lives went hand-in-hand, as we were banned for decades from returning to the island even for a visit.

Julin and Carmen Pelez del Casal, Ana Sofas paternal grandparents, came from an affluent family in Havana. Julin was the brother of Amelia Pelez del Casal, an artist of great renown whom I had met as a child on a visit to her lovely Havana home with my father, who was also a painter. I remember her as a kind woman who reminded me of my Aunt Anita, and I was drawn to her abstract paintings of tropical fruits and flowers framed by elements of Cuban architecture. Ana Sofas grandparents ultimately settled in Queens, New York, where they learned to cook Cuban food from a neighbor. (Servants had managed their Havana kitchen.) Her grandfather became an avid home cook who transmitted his understanding of Cuban food to his granddaughter. Growing up in Miami, Ana Sofa also ate at Cuban cafeterias, storefront restaurants, and bakeries, where decades of memory and longing and the mingling of disparate regional traditions, dominated by the western provinces, produced a generic Cuban cuisine.