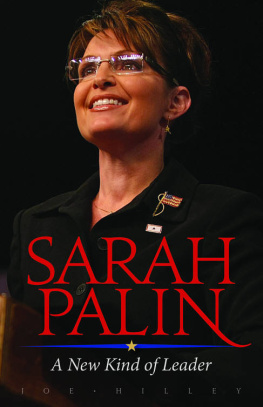

The Last Frontier

I dont believe that God put us on earth to be ordinary.

LOU HOLTZ

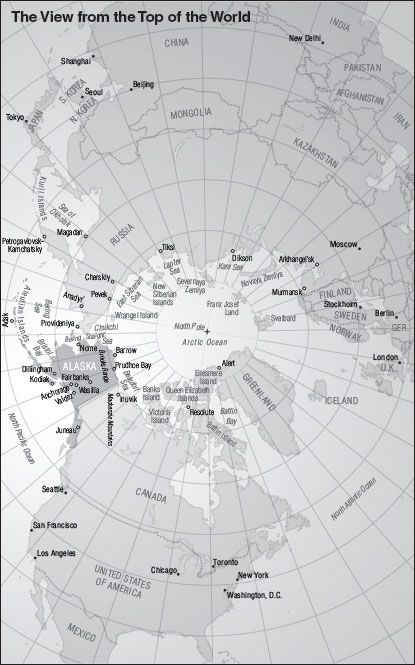

I t was the Alaska State Fair, August 2008. With the gray Talkeetna Mountains in the distance and the first light covering of snow about to descend on Pioneer Peak, I breathed in an autumn bouquet that combined everything small-town America with rugged splashes of the Last Frontier. Cotton candy and foot-long hot dogs. Halibut tacos and reindeer sausage. Banjo music playing at the Blue Bonnet Stage, baleen etchings, grass-woven Eskimo baskets, and record-breaking giant vegetables grown under the midnight sun.

Inching through rivers of people with Trig, our four-month-old son, cradled in my arms, I zigzagged from booth to booth, from driftwood art to honeybee keeping to home-brewed salmonberry wine. Bristol and Willow, our teenage daughters, roamed ahead with friends, heads together, laughing, thumbs tapping cell phones. Piper, seven, my constant sidekick since the moment she was born, bounced along at my hip, pinching off fluffs of cotton candy, her reward for patiently accommodating my stop-and-go progress through the crowd. For the most part, she was comfortable watching the grip-and-grin photos and hearing the friendly chitchat with constituents that I enjoyed as part of my job as governor of the state. Every few moments, I pulled my right arm free from baby duty to shake hands with folks who wanted to say hello.

Hey, Sarah! You never miss the fair!

Oh, my goodness, is that the new little one? Let me say hi to him

Price of energys pretty high, Governor. When are they gonna ramp up drilling?

A robins egg sky arced overhead, the brisk kick in the air hinting at winters approach. Like a family conga line, we wound our way among the vendors and exhibits: from pork chops on a stick to kettle corn, veggie weigh-ins, and livestock competitions. A local dance troupe took to the stage and the music blared, competing with the constant hum of generators and squealing kids on rides. Ahead, on my right, I saw the Alaska Right to Life (RTL) booth, where a poster caught my eye, taking my breath away. It featured the sweetest baby girl swathed in pink, pretend angel wings fastened to her soft shoulders.

Thats you, baby, I whispered to Piper, as I have every year since she smiled for the picture as an infant. She popped another cloud of cotton candy into her mouth and looked nonchalant: Still the pro-life poster child at the State Fair. Ho-hum.

Well, I still thought it was a nice shot, as I did every time I saw it on its advertisements and fund-raiser tickets. It reminded me of the preciousness of life.

It also reminded me of how impatient I am with politics.

A staunch advocate of every childs right to be born, I was pro-life enough for the grassroots RTL folks to adopt Piper as their poster child, but I wasnt politically connected enough for the state GOP machine to allow the organization to endorse me in early campaigns.

From inside the booth, a very nice volunteer caught my glance, so I tucked my head inside, shook hands, and thanked the gracious ladies who put up with the jeers of those who always protested the display. With their passion and sincerity, the ladies typified the difference between principles and politics. As I signed the visitors book, I saw Pipers picture again on the counter and became annoyed at my own annoyance. I still hadnt learned to accept the fact that political machines twist and distort public serviceand that, a lot of times, very little they do makes any sense.

Years before, I had seen our state speeding toward an economic train wreck. Since construction began in 1975 on what would become Alaskas economic lifeline, the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, it had grown increasingly obvious to everyday Alaskans that many of their public servants were not necessarily serving the public. Instead they had climbed into bed with Big Oil. Meanwhile, in a young state whose people clung to Americas original pioneering and independent spirit, government was growing as fast as fireweed in July.

It didnt make sense.

It seemed that true public service, crafting policies that were good for the people, had become increasingly derailed by politics and its infernal machines. But I had a drive to help, an interest in government and current events since I was a little kid, and I had become aware of the impact of common sense public policy during the presidency of Ronald Reagan. I was intrigued by political science in college and studied journalism because of my passion for the power of words. And I had been raised to believe that in America, anyone can make a difference.

So I got involved. I served first on the Wasilla City Council, then two terms as mayor, helping turn our sleepy little town into the fastest-growing community in the state. Then I served as an oil and gas regulator, overseeing the energy industry and encouraging responsible resource development, Alaskas main economic lifeline. In 2002, as my second mayoral term wound down, my husband, Todd, and I began to consider my next step. With four busy kids, I would certainly have enough going on to keep me occupied, even if I chose to put public service aside. And for a while, I did. But I still felt a restlessness, an insistent tugging on my heart that told me there were additional areas where I could contribute.

From what I could see from my position in the center of the state, the capital of Juneau seemed stocked mainly with good ol boys who lunched with oil company executives and cut fat-cat deals behind closed doors. Like most Alaskans, I could see that the votes of many lawmakers lined up conveniently with what was best for Big Oil, sometimes to the detriment of their own constituents.

When oil began flowing from Prudhoe Bay in 1977, billions of dollars flowed into state coffers with it. The state raked in more revenue than anyone could have imaginedbillions of dollars almost overnight! And the politicians spent it. Government grew rapidly. One quarter of our workforce was employed by state and local governments, and even more was tied to the state budget through contracts and subsidies. Everyone knew there was a certain amount of back-scratching going on. But an economic crash in the 1980s collapsed the oil boom. Businesses closed and unemployment soared.

During the oil boom, anyone who questioned the governments giving more power to the oil companies was condemned: What are you trying to do, slay the golden goose? But when the boom went bust, the golden goose still ruled the roost. By then, state government was essentially surrendering its ability to act in the best interests of the people. So I ran for governor.

I didnt necessarily get into government to become an ethics crusader. But it seemed that every level of government I encountered was paralyzed by the same politics-as-usual system. I wasnt wired to play that game. And because I fought political corruption regardless of party, GOP leaders distanced themselves from me and eventually my administration, which really was fine with me. Though I was a registered Republican, Id always been without a political home, and now, even as governor, I was still outside the favored GOP circle. I considered that a mutually beneficial relationship: politically, I didnt owe anyone, and nobody owed me. That gave me the freedom and latitude to find the best people to serve Alaskans regardless of party, and I was beholden only to those who hired methe people of Alaska.