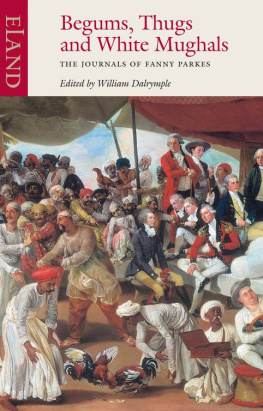

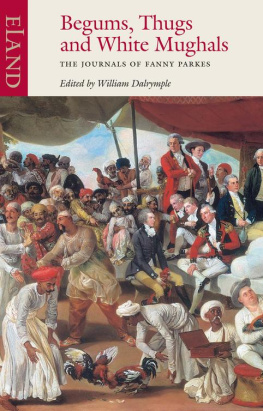

W E ARE RATHER OPPRESSED just now by a lady, Mrs Parkes, who insists on belonging to our camp, wrote Fanny Eden in January 1838. She has a husband who always goes mad in the cold season, so she says it is her duty to herself to leave him and travel about. She has been a beauty and has remains of it, and is abundantly fat and lively. At Benares, where we fell in with her she informed us she was an Independent Woman.

Fanny Eden was the sister of the Governor General, Lord Auckland, and the First Lady of British India. Fanny Parkes was the wife of a mentally unstable junior official in charge of ice making in Allahabad. The different status of the two women made friendship between them impossible, and posterity has been far kinder to the Eden sisters than to Fanny: Emily Edens Up the Country has long been regarded as one of the great classics of British Imperial literature and has rarely been out of print since it was first published in 1866; the critic Lord David Cecil went as far as placing the author in the first flight of English women letter writers. Fanny Edens Journals (recently republished as Tigers, Durbars and Kings: Fanny Edens Indian Journals, 18371838) are also much read and much reprinted, though they have never had the celebrity of her sisters work. In comparison Fanny Parkes Wanderings of a Pilgrim in Search of the Picturesque had no second edition, and has only recently re-emerged into print. In contrast to the fame of Emily and Fanny Eden, few have ever heard of Fanny Parkes. Fewer still have read her.

Yet anyone who today reads the work of these three women together can hardly fail but to prefer Parkes writing to that of her two more famous contemporaries and rivals. While the Edens are witty and intelligent but waspish, haughty and conceited, Parkes is an enthusiast and an eccentric with a burning love of India that imprints itself on almost every page of her book. From her first arrival in Calcutta, she writes how I was charmed with the climate; the weather was delicious; and I thought India a most delightful country, and could I have gathered around me the dear ones I had left in England, my happiness would have been complete. The initial intuition was only reinforced the longer she stayed in South Asia. In the twenty four years she lived in India, the country never ceased to surprise, intrigue and delight her, and she was never happier than when off on another journey under canvas exploring new parts of the country: Oh! the pleasure, she writes, of vagabondizing over India!

Partly it was the sheer beauty of the country that hypnotised her. Indian men she found remarkably handsome, while her response to Indian nature was no less admiring: The evenings are cool and refreshing the foliage of the trees, so luxuriously beautiful and so novel, is to me a source of constant admiration. But it was not just the way the place looked. The longer she stayed in India, the more Fanny grew to be fascinated by the culture, history, flowers, trees, religions, languages and peoples of the country, the more she felt possessed by an overpowering urge just to pack her bags and set off and explore: With the Neapolitan saying, Vedi Napoli, e poi mori, I beg to differ entirely, she wrote, and would rather offer this advice See the Taj Mahal, and then see the Ruins of Delhi. How much there is to delight the eye in this bright, this beautiful world! Roaming about with a good tent and a good Arab [horse], one might be happy for ever in India.

It is this sheer joy, excitement and even liberation in travel that Fanny Parkes manages so well to communicate. In the same way, it is her wild, devil-may-care enthusiasm, insatiable curiosity and love of the country that immediately engages the reader and carries him or her with Fanny as she bumbles her way across India on her own, wilfully dismissive of the dangers of dacoits or thugs or tigers, learning the sitar, enquiring about the intricacies of Hindu mythology, trying opium, taking down recipes for scented tobacco, talking her way into harems, befriending Maratha princesses and collecting Hindu statuary, fossils, butterflies, zoological specimens preserved in spirits, Indian aphorisms and Persian proverbs all with an unstoppable, gleeful excitement. Even when she dislikes a particular Indian custom, she often finds herself engaged intellectually. Watching the Churuk Puja, or hook swinging, when pious Hindus attached hooks into the flesh of their backs and were swung about on ropes hanging from great cranes for the amusement of the crowds below, some in penance for their own sins, some for those of others, richer men, who reward their deputies and thus do penance by proxy, Fanny wrote that: I was much disgusted, but greatly interested.

No wonder the Eden sisters turned their noses up at Fanny Parkes, complaining that she clung onto their party, taking advantage of their protection while touring the lawless roads of Northern India and taking the liberty of pitching her tent next to theirs: she was a free spirit and an independent mind in an age of imperial conformity. Behind the jibes of the Eden sisters (There is something very horrid and unearthly in all this, wrote Fanny Eden on March 17th, nobody ever had a fat attendant spirit before ) lies a clear uneasiness that Bibi Parkes (as they call her) is a woman whom they would like instinctively to look down upon, but who is clearly having more fun and getting to know India much better than they are.

The mental gap between the world of the Eden sisters and that of Fanny Parkes widened as time went on. The longer she stayed in India, the more Fanny Parkes became slowly Indianised. At one point in December 1837, after visiting an Indian Rani where Parkes acts as interpreter for the Eden sisters, Parkes urges with considerable vehemence that the Eden sisters should conform to Indian custom and accept the symbolic gifts offered to them as they leave, thus pleasing the Rani and avoiding giving offence. The Eden sisters worry that this might be seen as corruption and want to follow Company regulations and refuse the presents. There is a standoff, and eventually the Edens do turn down the gifts so giving huge offence to their host. Already Fanny Parkes is instinctively embracing Indian custom and trying to adapt herself to the Indian scene, trying to avoid rudeness and unpleasantness. The Eden sisters are more worried about what others will think: instinctively they want to play by the imperial rules, to keep within the accepted boundaries.

Parkes slow chutnification (to use Salman Rushdies excellent term) continued long after Parkes left the Edens camp. Over the following years, Parkes the professional memshib, herself the daughter of a colonial official (Captain William Archer), who came to India to watch over her colonial administrator husband was gradually transformed into a fluent Urdu speaker, and spent less and less of her time at her husbands mofussil posting, and more and more of her time travelling around to visit her Indian friends and assimilating herself to the world she discovered. Aesthetically, for example, she grew slowly to prefer Indian dress to that of the English. At one point watching Id celebrations at the Tj she notes how crowds of gaily-dressed and most picturesque natives were seen in all directions passing through the avenue of fine trees and by the side of the fountains to the tomb: they added great beauty to the scene, whilst the eye of taste turned away pained and annoyed by the vile round hats and stiff attire of the European gentlemen, and the equally ugly bonnets and stiff and graceless dresses of the English ladies.

Later, visiting the women in Colonel Gardners Khasgunge zenna, she again raises Indian ways over those of Europe:

[Mulka Begum] walks very gracefully and is as straight as an arrow. In Europe how rarely how very rarely does a woman walk gracefully! Bound up in stays, the body is as stiff as a lobster in its shell; that snake-like undulating movement the poetry of motion is lost, destroyed by the stiffness of the waist and hip, which impedes the free movement of the limbs. A lady in European attire gives me the idea of a German manikin; an Asiatic, in her flowing drapery, recalls the statues of antiquity.