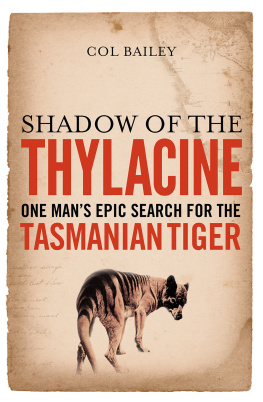

Tasmania is a beautiful island with lots of wild land.

Prologue

March 7, 2015: Im joined by my college friend Jenny Marshall Graves and her daughter, Erica, for a stroll along a California beach. We had lots to catch up on after fifty years apart. Jenny had become a widely respected geneticist, specializing in the chromosomes of native animals in Australia, her home country. She told me of her role in the scientific race to save the Tasmanian devil, the largest native Australian carnivore, from extinction. A strange and fatal disease called Devil Facial Tumor Disease (DFTD) had shown up out of nowhere and was sweeping across Tasmania, an island off the coast of mainland Australia and the home of these animals. The disease moved so fast that some scientists feared the species would be wiped out in the wild within twenty years.

As Jenny related the timeline of DFTD across Tasmania and the efforts of scientists to grasp what was happening, I became captivated by the story. Where had the disease come from? How did it spread? What was the causebacteria? Viruses? And could it be stopped?

In response to my many questions, Jenny said, Why dont you come to Australia to find out for yourself? I can connect you with other scientists involved, and you can stay with my family when youre in Melbourne.

How could I resist her generous offer? I jumped at it, and my husband, Greg, and I headed down under at the end of August the following year.

When Jenny described the situation, it seemed straightforwardDFTD was sweeping across Tasmania, and the devils in the wild would all be gone within a decade or two. Scientists hoped that they could then repopulate Tasmania with devils from captive populations. During my journey of discovery, however, I ended up witnessing enough twists and turns in this complicated and evolving story as in any fine whodunit.

Scientists Tackling DFTD

It takes many scientists in several different fields of work to figure out how to combat a problem like Devil Facial Tumor Disease. Ive chosen these four, since each has focused on different ways to investigate the disease in hopes of uncovering its secrets and helping the Tasmanian devil survive.

Jenny Marshall Graves, Geneticist

After earning her PhD in molecular biology at the University of California, Berkeley, Jenny returned to Australia with her American husband, John.

Jenny Graves receiving the Australian Prime Ministers Prize for Science in 2017 with Australian Senator Michaelia Cash and Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull.

Jenny believes that investigating the genetics of less-studied animals, from kangaroos to emus to Tasmanian devils, is vital to understanding genetics in general. During her long career she has analyzed the genomes of many species, including platypuses and dragon lizards. She has received international recognition for her research and, in 2017, she received the Australian Prime Ministers Prize for Science, a great honor.

Jenny enjoys an up-close and personal visit with a baby devil.

Menna Jones, Ecologist

Menna has always loved fieldworkgetting out into the wild to study how nature works. Her PhD work at the University of Tasmania focused on the biological family of predatory marsupials that includes Tasmanian devils and quolls and how changes in the biological environment affect the populations of different species. Menna had been studying the devils for years before the appearance of DFTD, providing background data on what things were like before DFTD came along and changed everything.

Menna Jones with a healthy devil caught in one of her traps.

She and her colleagues continue to study wild devils to increase the understanding of their behavior and ecological needs.

Greg Woods, Cancer Researcher

Ive always been interested in cancer and had lofty ambitions of working on a project that cured the disease, Greg explains. After receiving his PhD from the University of Tasmania, he spent time in Toronto, Canada, then returned to the Menzies Institute for Medical Research at the University of Tasmania to continue his research on leukemia and to teach immunology, or how immune systems fight disease. He says that when he learned about DFTD, it seemed that destiny had determined that my research would focus on the immune escape mechanisms of DFTD.

Greg is now semiretired, but studies at the Menzies Institute continue, as students and other researchers work on different aspects of DFTD and the immune system in order to understand this complex disease and find ways to prevent it.

Greg Woods takes a break from his work in the laboratory.

Alex Fraik, Graduate Student in Genomics

Researchers at Washington State University in Pullman, Washington, such as Alex Fraik, collaborate with researchers at the University of Tasmania, including Menna Jones, on vital studies of DFTD and how the devils and the disease are changing as they interact with one another and with the environment. Along with other students at both universities, Alex focuses her research on how Tasmanian devils are adapting to the challenge of DFTD by studying how their genetics have changed since the disease appeared. Alex wants to help inspire young people who care about the environment and the future of our planet to become scientists.