Part I

A Foundation for Culturally Responsive Design: How Culture, Context, and Language Shape Learning

Chapter 1

Culturally Responsive Design Matters

This chapter offers an overview of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and Culturally Responsive Teaching (CRT). We also present a rationale for Culturally Responsive Design, including planning learning environments and instruction for culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) students and English learners (ELs), and we describe expert learning and expert teachers.

Meet Felicia

Oh, boy! Felicia, a 9th-grade biology teacher, remarks as she reviews her class list with her colleague Allyssa, a 10th-grade geometry teacher. I dont know how Im going to do it this year. So many of my students are English learners and they come from all over. I dont even know how to pronounce many of the names on my class list.

Allyssa jumps in, Ive been using Culturally Responsive Teaching strategies for years, but this year, Im also going to integrate UDLUniversal Design for Learning.

I thought UDL was just for students with disabilities, Felicia counters.

Thats a common misconception about UDL, explains Allyssa. The UDL framework focuses on how we all learn, which includes the cultural variability and language learning needs of English learners.

Thats just what I need! declares Felicia. Im going to look into UDL.

Reflection How do Felicias concerns relate to your beliefs about your own instruction?

Cultural and Linguistic Diversity and UDL

Felicias situation is a common one. She is deeply devoted to her teaching, but as her schools student population changes, she finds it more difficult to meet their diverse learning needs. Shes heard about Universal Design for Learning (UDL) but has mistakenly believed that it is only helpful for students with disabilities. Thats a frequent misunderstanding. As Allyssa asserts, UDL helps educators to address the learning needs of all students, including those who are English learners (ELs).

According to the 2013 U.S. Census, almost 21 percent of people over the age of five speak at least one language other than English (U.S. Census, 2013). As classrooms in the United States become more culturally and linguistically diverse, educators are under pressure to meet the learning needs of ELs without diluting the focus of their educational goals and curriculum, and potentially sacrificing the progress of other students. The good news is that there is a framework they can apply to their lesson planning to reach all learners: Universal Design for Learning (UDL). UDL offers a unique lesson planning process that helps educators to develop learning environments that respond culturally and proactively to the needs of all learners, including culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) students and English learners (Chita-Tegmark, Gravel, Serpa, Domings, & Rose, 2012).

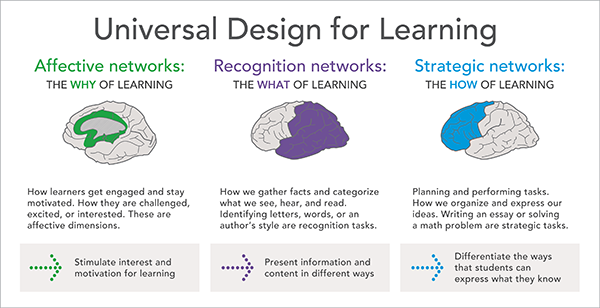

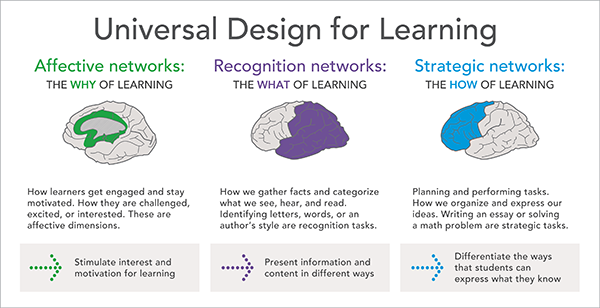

The UDL framework is defined in the Higher Education Opportunity Act (HEOA) of 2008 as a scientifically valid framework for guiding educational practice for all students, including students with disabilities and students who are limited English proficient (see 122 Stat. 3088). Based on learning and cognitive neuroscience research, UDL espouses a set of principles, illustrated in , that drive curriculum and learning environment design. The three UDL principles address specific sets of neural networks and are used by educators to engage learners in learning (i.e., Engagement, addressing the Affective networks), represent accessible and meaningful information (i.e., Representation, addressing with the Recognition networks), and offer options for expressing their learning (i.e., Action and Expression, addressing the Strategic networks).

The three UDL principles

CAST (2014). Used with permission

A key premise of UDLthat curricula should be designed from the outset with built-in flexibility and choicerequires some educators to make a conceptual shift from traditional ways of thinking about lesson design, curriculum, and learners. Educators who use the UDL framework understand that an inflexible, one-size-fits-all curriculum creates barriers that prevent students from reaching learning goals. Rather than expecting learners to access concepts, express their learning, and engage with assessments, materials, and methods in only one way, teachers who apply UDL to their teaching design flexible instruction with multiple options and choices (Meyer, Rose, & Gordon, 2014). Concisely stated, UDL is a framework that guides the shift from designing learning environments and lessons with potential barriers to designing barrier-free, instructionally rich learning environments and lessons (Nelson, 2014, p. 2).

Culturally Responsive Teaching

Another common framework for addressing the learning needs of CLD students and ELs that aligns well with UDL is Culturally Responsive Teaching (CRT). Geneva Gay, a pioneer in the field, defines Culturally Responsive Teaching as using the cultural knowledge, prior experiences, frames of reference, and performance styles of ethnically diverse students to make learning encounters more relevant to and effective for them (Gay, 2010, p. 31).

CRT builds on the learners culture. What do we mean by culture? Culture is not limited to ethnic or racial groups. Any group or community possesses culture. According to Ung (2015), culture includes a groups, communitys, or societys shared beliefs, values, norms, expectations, practices, and unspoken rules of conduct.

Culture is not limited to ethnic or racial groups. Any group or community possesses culture.

CRT involves valuing, building on, and teaching from each learners experiences and background knowledge gained through his own interactions within his culture. Gay (2010) doesnt stop there, though. She reminds us that CRT is not just how we design our lessons or structure the environment; CRT is how we acknowledge the importance of cultural diversity in learning. When we understand the value of diversity, we begin to celebrate and empower students intellectually, socially, emotionally, and politically by using cultural referents to impart knowledge, skills, and attitudes (Ladson-Billings, 2001, p. 1718).

Expert Learners and Expert Teachers

Helping students become expert learners is one of the primary goals of applying UDL to teaching practice. Frankly, no matter what their background, all students can become expert learners. Expert learners are not necessarily the most academically or linguistically proficient students in the classroom. Instead, expert learners are motivated and capable of managing their learning by focusing on a goal and identifying ways to reach that goal. They might not know all of the needed strategies when they begin working toward a goal, but they are resourceful about finding or using new strategies. In a nutshell, Meyer, Rose, & Gordon (2014) define expert learners as resourceful, knowledgeable, strategic, goal directed, and purposeful.

Essentially, the process of integrating UDL with the CRT framework depends on your ability, as an expert learner, to (a) find out what you need to know, (b) acquire the desired knowledge, skills, and attitudes, and then (3) use your new knowledge effectively (Nuri-Robins, Lindsey, Lindsey, & Terrell, 2012).

Together, UDL and CRT create a foundation for creating inclusive instruction and designing learning environments that heighten engagement, clarify academic content and language concepts, and offer meaningful and relevant expression options that help all learners become expert learners.

Next page