Copyright 2012 by Elizabeth Jai Pausch

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Archetype, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

Crown Archetype with colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pausch, Jai, 1966

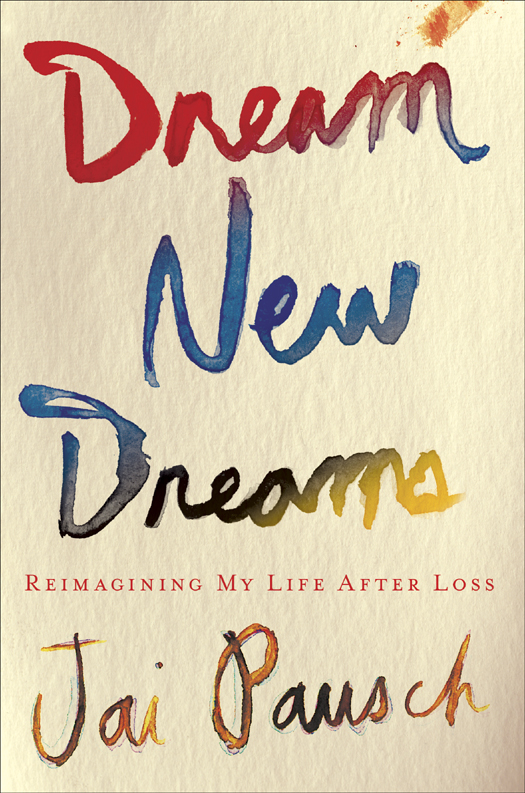

Dream new dreams : reimagining my life after loss / Jai Pausch. 1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Pausch, Jai, 1966 2. Women caregiversUnited StatesBiography. 3. PancreasCancerPatientsFamily relationshipsUnited States. 4. Pausch, RandyHealth. 5. DeathPsychological aspects. I. Title.

RC280.P25P38 2012

616.994370092dc23

[B]

2011046264

eISBN: 978-0-307-88852-5

Jacket design by Michael Nagin

Hand lettering on jacket by Mary Ciccotto

v3.1

To all the people

who care for ill and dying loved ones

and who struggle to do the best they can

without the proper training and resources to help them

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

In 2008 my husband died after a two-year battle with pancreatic cancer. While he received the best medical care possible, from the time he was diagnosed in 2006 until his death, I was his primary caregiver. In spring 2009, I participated in an event sponsored by my local Jewish Community Center (JCC) called the Week of the Caregiver. It was my first time speaking about my experience. In putting together my talk, I had to force myself to examine the struggles I had faced over the previous couple of years. First, I had to convince myself that my voice and perspective were valuable. Then I had to pull together my hard-won lessons, striving to take the ugly, nasty things I had been through and do some good with them; to spin some straw into gold so to speak, and to share them with others who were walking or might walk the same path. I was reassured to see that what I had to say struck a chord. The hundred people in the audience not only listened attentively, but some also took notes.

After the talk, I shook hands and listened as people shared their own experiences. Their grief and the guilt they felt for mistakes they perceived they had made echoed some of my own feelings. I asked myself, Where is the help for folks like us who tirelessly give to our dying loved one? Why wasnt the medical community concerned about the people who struggle to carry the medical burden while also meeting normal everyday demands? I wanted to hug them all and wipe away their self-doubts and replace it with self-forgiveness. I wished for a magic wand to create a support network at every oncology clinic for the caregiver whom the medical community assumes can and will manage complicated medical care while grappling with their own complicated and sometimes overwhelming emotions. Though I did achieve my initial goal, I walked away feeling like there was so much more that needed to be done.

Over the next two years, I had other opportunities to talk about the impact cancer has had on my life and on my family. Each time I spoke to a group or met with a cancer-related medical professional, I brought the caregivers role and needs to their attention. I wanted to shine a spotlight on the person in the treatment room who is so often overlooked, along with his or her needs and abilities. Although I couldnt travel and give talks and advocate for the caregivers silent plight, I thought a book could reach so many more people.

I wanted my story to be useful to others, not a tell-all about the professor who wrote The Last Lecture. I started by using my JCC talk as the basic framework for my narrative and explored the unique challenges and complex issues I had faced as a caregiver. I spoke with grief counselors and palliative care doctors and met with dozens of caregivers for both cancer and Alzheimers patients. Although each persons experience is unique, the overarching struggles are universal. Mining my own experiences forced me to dig into a wound still raw and painful, which had both positive and negative effects on me.

On the upside, writing has been a tremendous aid in helping me to heal myself; the process allowed me to see my strength and resilience. Ive been able to move forward in a new direction for myself and my family. Its also given me the opportunity to come to peace with a lot of bad stuff that happened.

On the down side, Im not able to put my past behind me completely. My years with Randy get brought up in some way, shape, or form every day. It could be an e-mail from a pancreatic cancer advocacy group or someone recognizing my name that resurrects my past. Three and a half years after Randys death I still suffer from nightmares, talking in my sleep as my subconscious relives the most traumatic moments during that very trying time in my life. My new husband, Rich, wakes me from my nightmares, quiets my sleep talk, and soothes me back to sleep. Its not the way I wanted to start a new chapter in my life. Its not the happy Hollywood ending I was hoping for, but I know my story doesnt end with this book.

Ultimately, my dream is that my story will legitimize what caregivers undergo willingly and bravely as they care for a person they love. Patients need and deserve support, but its time for us as a community to understand the suffering that is shouldered, sometimes silently, by our family members, neighbors, friends, and coworkers. We need to offer help to these people, to develop and implement programs at cancer centers and other organizations. We need to empathize with that person taking on the duty of overseeing the patients care and well-being. Finally, we need to care for the caregiver.

Living the Dream

S O I CAN PICK UP the block and throw it? Randy asked incredulously. He was learning about computer graphic research at the University of North Carolina, where I was working while studying for my PhD exams in comparative literature. Randy was a computer science professor at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh researching virtual reality and human-computer interaction. Standing in the virtual reality lab, he looked like a thirty-seven-year-old kid playing a Wii video game, game controller in hand. Instead of viewing the computer-generated world on a television mounted on a wall, he was looking at a screen inside a specialized helmet. Nowadays, many Americans are familiar with holding a device to make objects or avatars move within a video game. But fourteen years ago, this technology was not yet mainstream, nor was it a game; rather it was an experiment to see how compelling virtual reality could be. In this demonstration, throwing the block was not part of the programs functions, but Randy didnt know that, and he was asking a million questions. I had noticed his inquisitiveness earlier in the morning as we toured other parts of the virtual reality lab. Walking beside him, I could tell he was genuinely interested in our research, soaking it all in. It was obvious to me he was smart. What else would you expect of a Carnegie Mellon professor? But Randy was surprisingly down-to-earth. When I had first met him that morning, and in previous e-mails, he insisted I call him Randy, not Dr. Pausch. He had no need to stand on ceremony or demand acknowledgment of his title, which was a very refreshing change from the norm in academia. I felt instantly comfortable with him even after having only just met him. And I wanted to get to know him better.