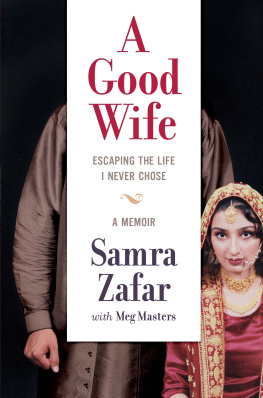

I wake to the crackling of bird calls outside my bedroom window, the anemic light of a Canadian spring morning seeping through the curtains. I lie very still, listening. The house is quiet. My in-laws are in the bedroom down the hall. My husband sleeps ten feet below me, in the den. My infant daughter slumbers peacefully beside me. At first, Im surprised to see her. Why didnt I put her in her crib in the room next door last night? Why is she still here with me? And then I remember. I rub a painful spot on my upper chest. My heart aches almost every morning, but today my ribs are sore as well.

As my drowsiness falls away, another feeling works its way through my body. A frayed, rippling tension, a growing brittleness: anticipation and fear. At any moment, the cold brick house will come alive, and I will be thrown together with the rest of the inhabitants. If all goes well, Ahmed will take his lunch and walk wordlessly out the front door, and I will start on a long, dull day, locked here in the house with his mother and my daughter. The hours will creep by, broken only by chores, television, empty chat.

But perhaps it wont be dull. Yesterday was not dull. Or at least it didnt end that way. And I have come to understand that in this new world of mine, anything other than grey monotony is scary. Anything else is dangerous.

My daughter shifts. I can hear my mother-in-laws slippers as she begins to pad about her room. It is time for me to go in to say salaam. It is time for me to head downstairs with the baby. It is time for me to make my husbands lunch. It is time for me to start my dreary routine.

As I rise, I realize that I am saying a little prayer. I am praying for luck. I am praying for another dull day.

M usic was drifting up from the tent, but I couldnt find the celebration in it. Instead it sounded haunting and hollow, like a distant echo of happier times. I knew that at any moment the dancing would start. It felt surreal to be trapped up here, all alone, reduced to watching and waiting. I had always loved family weddings, and I loved the dancing most of all. Enthusiastic as I was, I had never been able to resist taking charge of the choreography and hogging the limelight during our little performances.

Sitting in a bedroom in my uncles house in Karachi, I peered out the window at my family below. They were gathered under a tent, but the sides were open. I could see their brightly coloured clothes and sparkling jewellery. They were talking and laughing. I watched as my little sisters, Warda, Saira and Bushra, helped themselves to mithai and laddoo and other sweets that lined the enormous platters that were being passed from person to person.

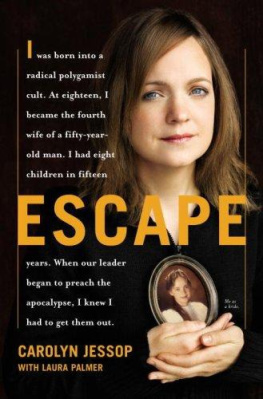

Tonight was my mehndithe pre-wedding music party a brides parents hold to formally present their daughter to her soon-to-be-husbands family. Earlier in the evening, I had been escorted downstairs to briefly join the festivities. My sisters and cousins had walked with me, holding my yellow dupatta over my head like a canopy. For half an hour or so, I sat on a raised platform, the dupatta draped over my head and my palm outstretched, a large paan leaf in its centre. One by one, all of the adult female guests approached me, putting a dab of henna in the centre of the leaf and a small morsel of mithai in my mouth. I tried to remember to keep my eyes down and not say too much, as for this short while I was the centre of attention. Ahmeds brothers, sisters, aunts and uncles studied me slyly, making comments about my hair, my height and the paleness of my skin. I felt like a new car or shiny watch that was being assessed by its owners friends. Then I was shepherded back upstairs so the celebrations could continue without the presence of the girl whose modesty needed to be protected. In two days time, I would no longer be a student, no longer a big sister and beloved daughter, no longer a person with any independence or autonomy. I would be a begumsomeones wife. I was just seventeen.

Sitting on the bed, in my new yellow-and-green dress, my dupatta abandoned beside me, I was seized by panic. I was supposed to be flattered by the proposal of a man eleven years my senior, a man who had a good job and a Canadian home. I was supposed to be relieved that I had avoided the terrible fate of spinsterhood. Most of all, I was supposed to be overjoyed by my impending marriage and the idea of joining my husbands family. But everything about the last few months felt like a terrible, twisted dream.

* * *

My family and I had arrived in Pakistan several months before and moved into the apartment my mother had bought a few years earlier as an investment. We had left behind in Ruwais, a small town in the United Arab Emirates, our spacious three-bedroom home and a tranquil suburban neighbourhood filled with succulent trees and fragrant blossoms. No one in my family had been happy about the move. My mother had been forced to quit her job. My three sisters and I had been torn from our friends and our school. My father was left to shuttle back and forth between his work in the oil refinery and his wife and children in Karachi. But there was no other way. It was cheaper for us to live in Karachi. And we needed to cut costs to pay for the wedding.

Our new home in Pakistan was a shock. The sweltering summer heat beat its way through the doors and windows, filling the cramped space with fetid, humid air. Used to air conditioning, my sisters and I spent most of our waking hours huddled in my parents tiny bedroomthe only room that had AC. When we did move about the place, we stepped carefully, watching out for the cockroaches and other bugs that crunched under our feet or scuttled across our toes if we werent careful. For young girls in Pakistan, there was no playing outdoors or riding our bikes. No tennis or squash or cricket. And when we went outside, we had to leave our jeans and T-shirts tucked in the closet, donning instead the traditional shalwar kameeza long tunic and flowing pantsour heads and chests covered with a dupatta. The streets, with their emaciated stray dogs, flea-ridden cats and skittering lizards, took us months to get used to.

A week before the wedding, our out-of-town relatives descended upon us. While some stayed with my grandfather and my other relatives, a number wrestled their suitcases into our already impossibly crowded apartment. Once ensconced, they threw themselves into the wedding preparations. My uncles shuttled back and forth to the banquet hall, checking on the arrangements there; my aunts fussed about clothes and bangles and flowers. My sisters and cousins squeezed into the living room to work out the dances they would perform at the two mehndis.

And I stood in the midst of it all, dumbfounded by the activity. It was my wedding, but all the sacrifices people were making, all the expense and exertion they were putting in, seemed to have nothing to do with me. No one sought my input on the flowers or the food we might serve. No one invited me to choose music or even a colour of lipstick. No one asked me if I liked the clothes that they had selected for me to wear at the various dinners and parties. (My actual wedding dress and jewellery were being picked out for me by Ahmeds family and would be presented to my family at his mehndi.) It was like standing on the bank of a river, watching the water swell and surge and knowing that I would be pulled into it, helpless, at any moment.