Copyright 2006 Omnibus Press

This edition 2009 Omnibus Press

(A Division of Music Sales Limited, 14-15 Berners Street, London, W1T 3LJ)

ISBN: 978-0-85712-027-4

The Author hereby asserts his/her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with Sections 77 to 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, expect by a reviewer who may quote brief passages.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of the photographs in this book, but one or two were unreachable. We would be grateful if the photographers concerned would contact us.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Visit Omnibus Press on the web at www.omnibuspress.com

For all your musical needs including instruments, sheet music and accessories, visit www.musicroom.com

For on-demand sheet music straight to your home printer, visit www.sheetmusicdirect.com

Contents

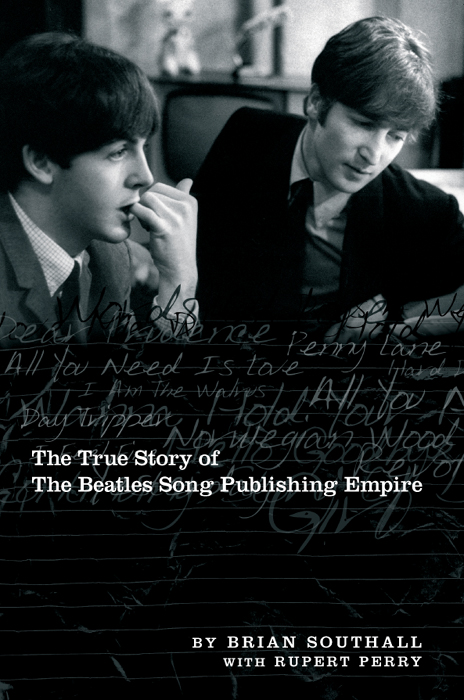

The strange thing is that we never owned our own publishing, it was always getting bought and sold. Paul McCartney

Song writing should be treated as the lifeblood of popular music. Michael Jackson

BRIAN SOUTHALL worked as a journalist with Music Business Weekly, Melody Maker and Disc before joining A&M Records. He moved to EMI Records and EMI Music where, during a 15 year career, he served in press, promotion, marketing, artist development and corporate communications. From 1989 he was a consultant to Warner Music International, HMV Group and both the BPI (British Phonographic Industry) and IFPI (International Federation of the Phonographic Industry).

Among other books he has written are the official history of Abbey Road Studios, the AZ of Record Labels and the official story of the BRIT Awards, in addition to editing the best-selling Complete Beatles Recording Sessions.

RUPERT PERRY CBE spent 32 years with EMI during which time he served as President of EMI America, EMI Records UK and EMI Europe. He was elected Chairman of the BPI between 1993 and 1995 and also served as Chairman of IFPI Europe for four years from 1998 during which time he was awarded the CBE for services to the British music industry. During his 39 year career in the music industry he has also been honoured with the 1997 Music Week Award for Outstanding Achievement, the 1999 International Managers Forum British Music Roll of Honour and the IFPI Medal in 2004 for services to the International recording industry.

FOREWORD

S o, why shouldnt Michael Jackson own the copyright to over 250 classic pop songs written by John Lennon and Paul McCartney during the golden period that was known as the Swingin Sixties? Perhaps its just as relevant to ask why he would want to spend many millions of his hard earned dollars acquiring songs that were written before his tenth birthday.

Either way, its a subject that both animates and excites artists, composers, music publishers and fans alike and, for a long time, has rankled with the surviving member of the worlds most successful song writing partnership.

In the world of music publishing copyright is all-important. For song writers and publishers alike the most important five words are always the same never give up a copyright. While Lennon & McCartney never actually gave up the rights to their songs, they did somehow manage to lose them along the way as deal after deal turned their creations into increasingly valuable company assets.

While dealings involving The Beatles songs and their Northern Songs catalogue throughout the Sixties, Seventies and Eighties were never illegal, and in many ways simply reflected what was normal business practice at the time, there is no doubt that while Lennon & McCartney were not always given the best advice, there were others who made decisions about their songs without either their knowledge or consent.

How much the two composers and their manager Brian Epstein knew or understood about music publishing will perhaps forever remain a mystery but there is no question that certain people around them had a much greater understanding of the value of copyrights.

In the music business the worlds of record companies and music publishers have one thing in common songs. For record companies they are the essential commodity that creates the record which hopefully becomes a hit and is subsequently broadcast regularly on radio and television and performed live on stage. The success of a particular record also means increased profile and public awareness for an artist, and helps to bring some return on the companys investment.

Music publishers, however, are less concerned with the record than with the actual song. The song writer who in many cases will also be the recording artist is their investment and the songs he or she creates are their livelihood. Copyrights are their business and in their business those five most important words about never losing ownership of a song are just as relevant today as they were a hundred years ago.

Without a music publisher, song writers are pretty much left to their own devices when it comes to getting their songs played, performed or recorded and being paid for the privilege. No matter how famous or successful you are as a composer, you will still need a music publisher in some form or another to monitor, promote and organise your catalogue, protect your copyright and collect your earnings.

The concept of copyright stretches back to 1847 when French songwriter Ernest Bourget visited a caf in Paris where he heard his music being performed as entertainment for the customers. Arguing that his music had been consumed in the same way as he had eaten the cafs food, he not only refused to pay the bill but sued the caf. The court ruled in his favour and ordered the cafs owners to pay him substantial damages. As a result, the first French society to protect the creators rights and collect royalties on their behalf was established and soon after societies sprang up in other countries.

Music publishing was probably the original commercial music business and it grew out of the arrival of cheap printing processes which made sheet music easily accessible to 19th century music lovers. Selling sheet music containing the music notation and lyrics of popular songs which could be played in saloons, cafes, restaurants, theatres, clubs and the home particularly after the invention of the upright piano in 1827 established music publishing as a major business over two centuries ago.

With the invention of the phonograph, songs began appearing on cylinders and then discs as the commercial record business emerged. With radio and television replacing the piano as the major home entertainment, music publishers and the songs and song writers they signed, represented and promoted continued to dominate the music industry.

In the years after the Second World War music publishing was still dependent on song writers and composers to provide songs for artists to perform, primarily on stage but also on the radio and in films. A traditional music publisher in the London of the Forties and Fifties would have a trade department that concentrated on selling sheet music which, in the days before record charts, was the only way of determining a songs popularity.

Next page