Copyright 2006 by Scott David Plumlee

First published in 2006 by

Watson-Guptill Publications,

Crown Publishing Group, a division of

Random House Inc., New York

www.crownpublishing.com

www.watsonguptill.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form or by any meansgraphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage-and-retrieval systemswithout written permission of the publisher.

All projects by Scott David Plumlee

All jewelry photography by Scott David Plumlee

All step by step photography by Lisa Eastman

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Plumlee, Scott David.

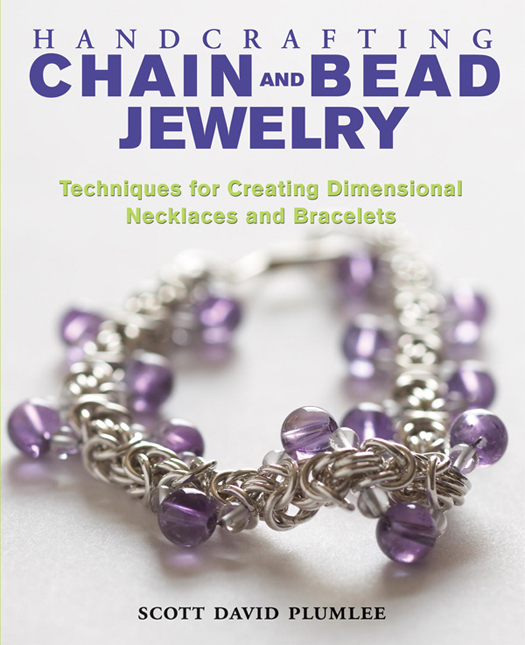

Handcrafting chain and bead jewelry : techniques for creating dimensional necklaces and bracelets / Scott David Plumlee.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8230-2299-1

ISBN-10: 0-8230-2299-4

eBook ISBN: 978-0-7704-3469-4

1. Jewelry making. 2. Metalwork. 3. Beadwork. 4.

Chains (Jewelry) I. Title.

TT212.P55 22006

745.5942dc22

2006004438

Senior Acquisitions Editor: Joy Aquilino

Editors: Anne McNamara and John A. Foster

Senior Production Manager: Ellen Greene

Cover photograph: Paul David OHanlon

Cover design: Julie Duquet

A Note to Readers:

When working with pliers, electric screwdrivers, wire, and other materials presented in this book, readers are strongly cautioned to follow manufacturers directions, to heed warnings, and to seek prompt medical attention for an injury. In addition, readers are advised to keep all potentially harmful supplies away from children.

v3.1

Contents

Preface

Welcome to my world, where art and science merge, creating endless possibilities for dynamic chain jewelry! The chain-making techniques illustrated in this book utilize simple hand tools, thus freeing artists from the confines of the metalworking studio.

During my singular jewelry course, I studied the finer techniques of silversmithing, from soldering bezel settings to using a variety of power tools. Upon completing a spinning triptych pendant, I realized that the product appeared sterilemade by machine, not by hand. Furthermore, I felt that power tools were quite loud, and on account of their dependency on electricity, hindered my creativity and mobility.

When I set off to travel around the world in 1996, I craved a portable craft that would provide a satisfying artistic outlet. I chose to embrace the elements of silversmithing I enjoyed and to reject the rest. I gave up my crutch of studio and hot torch for a quiet, hands-on, instantly gratifying, and meditative process. For the greater part of five years, I traveled across thirty-two countries on four continents. I utilized my chain-making skills to influence border guards, to barter for goods and services, and to provide gifts to family, friends, and a few pretty ladies along my path.

When I settled in Seattle, Washington, I went back to the blackboard to develop a mathematical formula based on the Golden Ratio of Pi (3.14) that utilized individual wire gauge to determine the ideal diameter for jump rings. The jump rings I made with this formula produced chains of physical linear strength and eliminated the necessity of soldering each ring. This new method opened the door to a whole new world of creative possibilities, which eventually led me to develop over sixty unique chain designs.

In 2001, I began teaching chain-making workshops. I developed handouts with step-by-step instructions to guide my students through the chain-making process. These handouts eventually became the basis for this book, and conversely this book would not have been conceivable without these teaching experiences.

The opening section of the book describes the foundations of the classic Byzantine chain. Then a selection of original chain designs, based on the Byzantine, is introduced and accompanied with bead-setting techniques. These chain designs are divided into four chapters: Linear Designs, Additive Designs, Combined Designs, and Composed Designs.

The projects should be seen as building blocks, each introducing skills that can be carried through to the next project.

While my desire is to share with you the knowledge and skills that I have acquired over the years, my ambition, above all else, is for you to have fun with this bookshare it with a friend, even take it on a vacation. Go to a Caribbean beach and chain away the sunsets.

The Byzantine Chain

This book is dedicated to unraveling the mysteries of the Sequential Byzantine chain. All fifteen original chain designs outlined in this book are derivatives of this ancient chain pattern. The origin of the Byzantine chain is a mystery; I have seen slight variations of it all over the globe. It is known by many different names to many different civilizations.

I was first introduced to the Byzantine chain while I was an undergraduate studying pottery and silversmithing at the Appalachian Center for Crafts in Tennessee. I found in their eclectic library an old Taiwanese text with no translation and only hand-drawn pictures of a beautiful chain pattern. After countless hours toiling with lopsided rings, a half-dozen botched chains, and the angst of trial and error, I eventually developed an efficient motion for making this chain, yet I didnt know its name.

Since then, I have seen this chain pattern labeled the Byzantine or, more specifically, the Sequential Byzantine chain, in numerous publications. I can only assume that this is a reference to the thirteenth-century Byzantine Empire. Ive also seen several books that label this chain pattern as the Idiots Delight or, more specifically, as the Sequential Link Idiots Delight. Although I really like this name, I always thought it would be difficult to market a workshop on handcrafting the Idiots Delight, so I kept with the more universally recognized Byzantine designation.

The three Byzantine chains pictured here were made using sizes 14-, 16-, and 18-gauge jump rings, shown from left to right. These are the three gauge sizes used to create the designs in this book .

The Inca Puo Chain

While trekking through South America, I witnessed a blacksmith crafting a repetitive chain. He salvaged copper wire by unbraiding old electrical cables. After a charcoal annealing, he pulled the red-hot wire through a drawplate to create a 16-gauge round wire. He then wrapped the cooled wire around a hand-whittled wooden dowel and cut it with a small handsaw. What amazed me most was that he did not use pliers to bend the rings, just his calloused fingertips. I learned that in Spanish this chain was known as the Inca puo . Puo translates as a clenched fist, and each knot in this repetitive chain represents the clenched fist of the Incan warrior. It traditionally is given as a mark of courage to the young men in a tribe.