Table of Contents

All of the authors proceeds from this book go to ScholarMatch, a nonprofit organization that increases college access for low-income students of exceptional promise.

For more information, visit www.scholarmatch.org.

Foreword

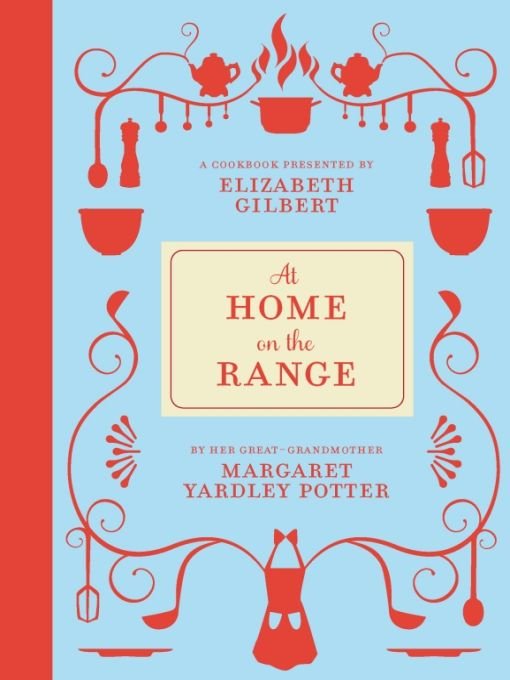

by ELIZABETH GILBERT

This cookbook has been around my family a lot longer than I have. At Home on the Range was first published in 1947, back when my fathernow a grey-bearded man in flannel shirtswas a towheaded toddler in droopy pants. The book was dedicated to my Aunt Nancy, whom the author described as a five-year-old child already in possession of the two prime requisites of a good cook: a hearty appetite and a sense of humor. (Nancy is still in possession of both those fine qualities, I am happy to say, but she is now a grandmother.) The copy of the cookbook that I inherited belonged to my own grandmother, our beloved and long-gone Nini, whose penciled notes (Never apologize for your cooking!) are still in the margins. The book was written by her mothermy great-grandmotherwho was a cooking columnist for the Wilmington Star, and who died of alcoholism long before I was born. Her name was Margaret Yardley Potter, but everyone in my family called her Gima, and until this year, I had never read a word of her writing.

Of course, Id seen the book on family bookshelves, and had certainly heard the name Gima mentioned with love and longing, but Id never actually opened the volume. Im not sure why. Maybe I was busy. Maybe I was prejudiced, didnt expect much from the writing: the original jacket photo shows a kindly white-haired woman with set curls and glasses, and maybe I thought the work would reflect that photodated and ordinary, JELL-O and SPAM. Or maybe I am just a fool, willing to travel the world in pursuit of magic and exoticism while ignoring more intimate marvels right here at home.

The author photo from the first edition.

All I can say is that I finally picked up Gimas cookbook this spring at the age of forty-one, when I found it at the bottom of a box, which I was finally unpacking because I was finally settling into the house where I hope and pray to finally stay put. I cracked it open and read it in one rapt sitting. No, that s not entirely true: I wasnt really sitting, or at least not for long. After the first few pages, I jumped up and dashed through the house to find my husband, so I could read parts of it to him: Listen to this! The humor! The insight! The sophistication! Then I followed him around the kitchen while he was making our dinner (lamb shanks), and I continued reading aloud as we ate. Then the two of us sat for hours over the dirty dishes, finishing a bottle of wine and taking turns reading the book to each other by candlelight.

By the end of the night there were three of us sitting at that table.

Gima had come to join us, and she was wonderful, and I was in love.

What you have to understand about my great-grandmother, first and foremost, was that she was born rich. Not stinkin richnot Park Avenue rich, or Newport richbut late nineteenth-century Main Line Philadelphia rich, which was still pretty darn rich. I tend to forget that we ever had that strain of wealth and refinement in our family (probably because both were long spent by the time I arrived) butdecidedly unlike her descendantsGima grew up with sailboats and lawn tennis, white linens and Irish servants, social registers and debutante balls.

The young Margaret Yardley was not a beauty. That would ve been her little sister, Elizabeth (for whom I was named.) A family visitor, introduced to both girls when they were in their teens, let his eyes rest on my great-grandmother and said, Well, you must be the one who cooks. Well, yes, she was the one who cookedand she also happened to be the charming and popular one. With such nice credentials, she probably couldve married just about anyone. For reasons lost to history, she chose to marry my great-grandfather Sheldon Pottera charismatic Philadelphia lawyer full of brains and temper and narcissism, who was witty but lacerating, sentimental but unfaithful, whod passed the bar at age nineteen and could quote Herodotus in Greek, but who never developed a taste for work. (As one disapproving relative later diagnosed him, He was too heavy for light work, and too light for heavy work.)

Sheldon Potter did, however, develop a taste for fine living and for serious overspending. As a result, Gima slid deeper and deeper into reduced circumstances with every year of her life. As she relays (uncomplainingly!) in the first pages of her cookbook, over the course of her marriage she was shuttled financially and physically between a twelve-room house in the suburbs, a four-room shack in the country, numerous summer cottages, and a small city apartment. She passed the lean years of World War II on an isolated and heatless farm on Marylands Eastern Shore, which was probably the furthest imaginable cry from her classy Edwardian upbringing.

Listen, she made the best of it. For one thing, her financial troubles were not entirely Sheldons fault: Gima was quite the spendthrift herself, and she faced life with a Jazz Age sensibility that can best be summed up in one gleeful, reckless, consequence-be-damned word: Enjoy! Moreover, she had an instinct for bohemian livingmaybe even a preference for it, and that instinct informs the winningly informal tone of At Home on the Range. While she admits, for instance, that there is no substitute for either good food or a comfortable bed, she submits that pretty much everything else in the material world can be substituted, or improvised, or gone without, or cobbled together from junk-store treasures. Books can be borrowed, wildflowers can be picked from roadside ditches, barrels can be transformed into perfectly good little tables, orange crates make for excellent chairs, cheap onions can replace expensive shallots without anyone s tasting the difference, and there s no need whatsoever to be ashamed of a kitchen that resembles an old-fashioned tin peddlers cart. All your guests really need from you, Gima assures us, is your warm welcome, plenty of good food, and a steady supply of ice for cocktails. Provide that, she promises, and a world of friends will beat a path to your door.

So she did provide, and so a world of friends did beat a path to her door, but it should not be inferred that her life was necessarily easy just because her houseguests adored her. Married to a man whom my father describes as impossible, constantly in debt (sometimes slipping out of foreclosed homes just ahead of the sheriff s arrival), struggling with the alcoholism that would periodically land her in psychiatric clinics and grim hospital wards, my creative but constrained great-grandmother was not the first or the last woman in the history of female hardship to take refuge in food.

![J K Rowling - Harry Potter [Complete Collection]](/uploads/posts/book/117015/thumbs/j-k-rowling-harry-potter-complete-collection.jpg)