Table of Contents

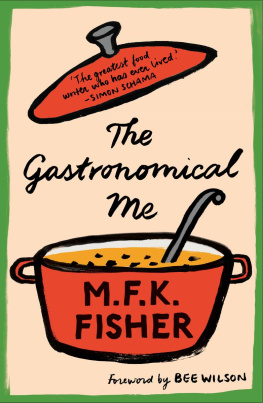

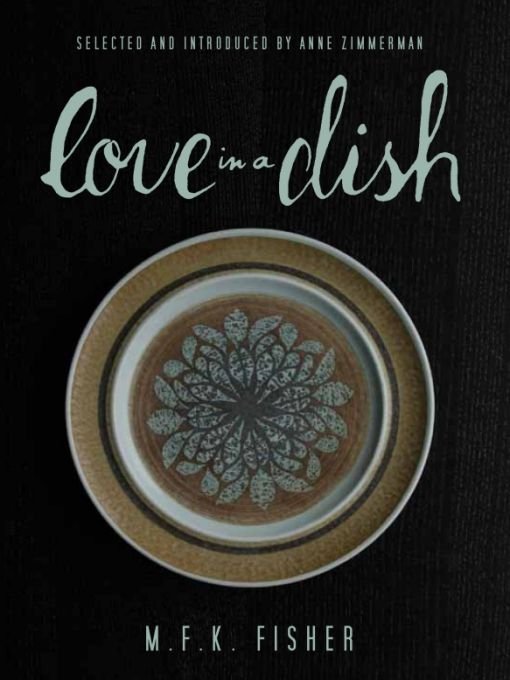

MARY FRANCES KENNEDY FISHER (1908 1992) is considered one of the greatest American food writers of the twentieth century. In 1929, the newly married Fisher travelled with her husband to Dijon, in France, where she tasted real French cooking for the first time and learned how to live and eat well and economically. She returned in 1932 to an American appetite weakened by the Great Depression and began to write essays of her own. The author of many books, including the wartime classic How to Cook a Wolf, she aimed always to inspire cooks and combined recipes with reflection, anecdote and passionate storytelling. Considered the poet of the appetites by John Updike, and hailed by W. H. Auden as the greatest American prose writer, her culinary essays have become American classics.

Introduction

By Anne Zimmerman

The title of this book: Love In a Dish... and Other Culinary Delights, was picked long before I sat down to write an introduction to this small collection of amusing, occasionally sad, and always profound essays. This is often how it works in the book world. The title comes first, and the introduction last, whereas in school, youd pen your introduction right off the bat, and then finish it off with a zinger of a title.

But this book is far more than a petite chocolate box of M.F.K. Fisher delights. Its a feast of classic M.F.K. Fisher. Theres an article about the astonishing perfection of the egg, trademark Fisher musings on oysters, and advice on how to seduce (and keep) a husband. The essays illustrate the arc of her brilliant career as one of Americas greatest food writers and gastronomes.

The selections were not easy to pick, or find. Six months after Gourmet magazine shuttered, I sat in the reading room of the Schlesinger Library on the campus of Harvard University where M.F.K. Fishers archives are stored. Beside me on a rolling library cart were five oversized boxes, filled with magazines. There were stacks of House Beautiful, piles of Travel and Leisure, and a thick collection of Gourmet.

I flipped through the pages, a bit horrified. Many of these print magazines were out of business or teetering on the edge. With each passing, a collection of work by M.F.K. Fisher was cataloged and delegated to deep library storage boxes. There they waited for someone like mea scholar and fanto call them forth from the basement.

But how many people, I wondered, would make the journey I had: requiring the requisite permissions, the red-eye flight across the country, and the hours of sitting in a chilly library reading room. Not many. The result? As beloved as she is, it is becoming increasingly hard to enjoy the full range of M.F.K. Fishers work. As beloved as she is, many of her characteristically amusing pieces are now officially hard to find, even for the most devoted.

Thus, I took my task seriously. For this book, I wanted essays that were stylistically adept and beautifully writtentypically poised and completely M.F.K. Fisher. Yet, I also wanted pieces that, perhaps, werent as popular and well-known as many of the excerpts from her favored, oft quoted books like Serve it Forth, The Gastronomical Me, and An Alphabet for Gourmets.

I had originally fallen in love with M.F.K. Fisher, the book author. I was spellbound by her affair with food and the way, it seemed, she viewed meals as one of the central characters in the most profound moments of her life. But the work I found in those boxes of magazines introduced me to a M.F.K. Fisher I hadnt thought much about. Yes, Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher was the author of many honest, entertaining, and gastronomically rich books. But she also churned out numerous shorter articles. These were the words that paid the bills, bought groceries for her family, and purchased clothes or a fancy new hat.

Several of the pieces in this book are ones that were periodically due to demanding editors. These were pieces she loved to write because they were quick, easy, and enjoyable. Yet they also represented numerous pressures: the pressure to create, to sustain her reputation as a culinary doyenne, to earn money and notoriety, and fame. From a practical standpoint, they were also, I imagine, assignments that were occasionally frustratingjust how many ways could she describe a delightful ladies lunch?

As a working writer who began her career in the late 1930s, M.F.K. Fisher wrote with extreme honesty about her personal hungers and the things that made her happyspecifically the resounding pleasure of a deeply satisfying meal.

The first piece in this book, casually titled Uncle Evans recounts a formative cross-country trip with her uncle. She was a teenager, he an accomplished lawyer and sophisticate. It was her true introduction to travel: I probably heard and felt and tasted more than either of us could ever be aware of, she admitted.

But it was this awareness of food, and the role it played in her life and the lives of others that birthed a writing career. M.F.K. Fisher loved Europe, particularly France, and wrote about it often. In I Was Really Very Hungry she teases readers with a grandiose story of how she was an accidental victim of passionate gourmets at a country restaurant where the waitress and chef, recognizing her deep love for French cuisine, fed her an elaborate, rich meal.

Some of her most delightful writing was about forgotten foods. From the ordinary beauty of the potato in Let the Sky Rain Potatoes, to pondering the secrets contained in the fragile eggshell in How Not to Cook an Egg, Fisher was devoted to the idea that even the most ordinary ingredients could be amazing if prepared properly.

She loved oysters so much, that the shell slurping research required to pen Love is a Pearl, and Love Letter to an Empty Shell, may have unintentionally inspired another set of pieces: G is for Gluttony, and Once A Tramp, Always.

It is a curious fact she wrote in the essay on gluttony, composed for Gourmet magazine, that no man likes to call himself a glutton, and yet each of us has in him a trace of gluttony, potential or actual. She was not prone to physical overindulgence, but her brain engaged in it often. She recalled again and again the foods of her childhood, of France, and even hungered for odd dishes shed eaten only once, but longed for, like rich mashed potatoes with swirls of deep red ketchup.

M.F.K. Fishers hungers were real; she wanted both food and love, and seemed to realize that the two were undeniably linked. There can be no warm, rich home life anywhere else if it does not exist at the table, she wrote in the piece for House and Beautiful that inspired the title of this book, and in the same way there can be no enduring family happiness, no real marriage, if a man and woman cannot open themselves generously and without suspicion one to the other over a shared bowl of soup as well as a shared caress. It was an witty admonition, but one steeped in heartbreak: M.F.K. Fisher was divorced, widowed, and then divorced again.

In Two Kitchens in Provence, she describes food as her lodestar. Yet in an essay for California magazine called Wine is Life, she remarks that wine is life, and my life and wine are inextricable. She wasnt being capricious. She was a dramatic woman, and prone to extremes. She loved travel, reading, big ideas, and a chilled martini at the end of a long day. But she was also, at times, a single mother, a harried wife, a tired caretaker to ailing parents. Her writing revealed little of this. Instead, it was armchair travel to other countries and into other worlds where lively dinners have several courses and are always paired with the perfect glass of wine.