To Warren

for believing in me and

supporting me ceaselessly

Copyright 2015 by Kian Lam Kho

Photographs copyright 2015 by Jody Horton

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Clarkson Potter/Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.clarksonpotter.com

CLARKSON POTTER is a trademark and POTTER with colophon is a registered trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kho, Kian Lam.

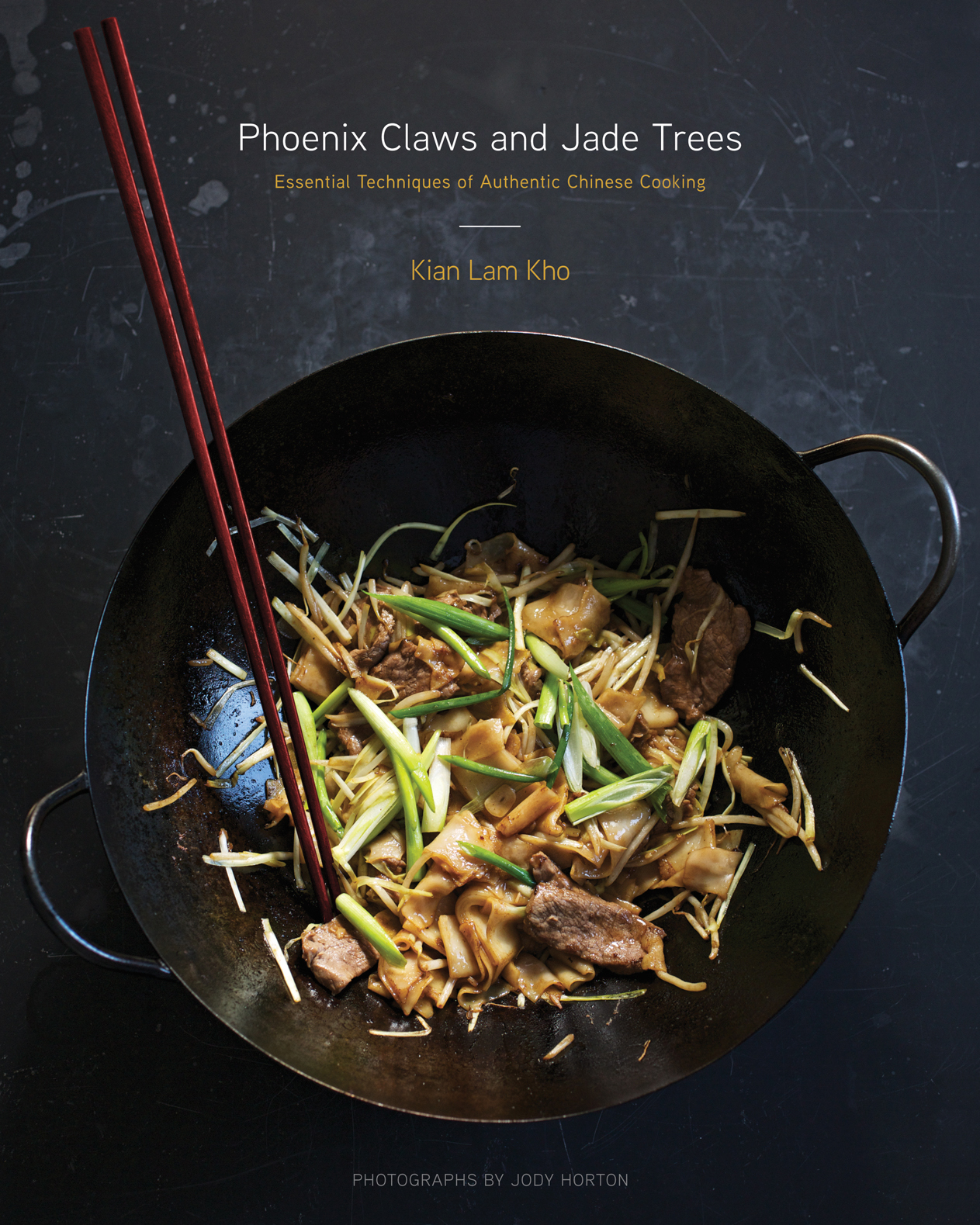

Phoenix claws and jade trees : essential techniques of authentic Chinese cooking / Kian Lam Kho ; photographs by Jody Horton. First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Cooking, Chinese. I. Title.

TX724.5.C5K485 2015

641.5951dc23

2014046694

ISBN9780385344685

eBook ISBN9780385344692

Hardcover Book Design by Jan Derevjanik

Cover design by Jan Derevjanik

Cover photographs by Jody Horton

Prop styling by Johanna Lowe

Food styling by Suzanne Lenzer

v4.1_r1

a + prh

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

The Essence of Chinese Food

CHAPTER 2

The Chinese Kitchen

CHAPTER 3

The Chinese Pantry

CHAPTER 4

Basic Ingredient Preparation

CHAPTER 5

Chinese Stocks

CHAPTER 6

Harnessing the Breath of a Wok

CHAPTER 7

Explosion in the Wok

CHAPTER 8

Dipping in Oil

CHAPTER 9

Flavoring with Sauces

CHAPTER 10

The Virtues of Slow Cooking

CHAPTER 11

The Intricacy of Boiling

CHAPTER 12

The Power of Steam

CHAPTER 13

The Making of Hearty Soups

CHAPTER 14

Playing with Fire

CHAPTER 15

Enriching with Smoke

CHAPTER 16

Appetizing Cold Dishes

CHAPTER 17

Sweet but Not Dessert

INTRODUCTION

Phoenix claws and jade trees are poetic metonyms, or metaphorical substitutions, youll find on many Chinese restaurant menus. Phoenix claw () is a synonym for chicken feet, and jade tree () is used for gailan , or Chinese broccoli. To most Chinese diners, this is familiar terminology, and I grew up learning it naturally at daily meals. But for many Westerners, authentic Chinese cuisine remains just out of reach linguistically and geographically. Yet with so many ingredients readily available and a wok just one click away online, its time to extend these thrilling and transportive flavors to eager home cooks everywhere.

In this book I demystify Chinese cooking by taking a unique approach. I believe that the cuisine is easiest to learn by technique. A dry stir-fry is no more difficult to prepare than a moist one; the key is to know which technique to use for which ingredient and for which final result. Armed with this knowledge, you can not only re-create dishes from all over China and many East Asian countries, but you can cook almost any ingredient in any fashion youd like. If you discover you love dry stir-fry with leeks and you are wild about duck, you can combine the two to make a successful Chinese dish all your own.

As China opens up to the world, her emigrants bring many regional cooking traditions to their adopted countries. They introduce new ingredients and open restaurants to satisfy their longing for food from home. At the same time, Western expatriates flock to China as companies from all over the world scramble to do business there. After short stints in China they return home, yearning to re-create the incredible array of food they experienced abroad.

This confluence of immigration and business travel creates new demands and sets higher standards for authentic Chinese food outside China. No longer are we satisfied with Beef with Broccoli and General Tsos Chicken. We now demand Xinjiang Lamb Burgers and Lan Zhou Pulled Noodles. From New York to Melbourne, people are curious about authentic Chinese food.

My own experience of cooking Chinese food in America parallels the narrative of these new Chinese immigrants. Arriving in America from Singapore in the 1970s to attend university in Boston, I longed for the abundance of wonderful food from home. At that time most restaurants in town were still serving up chop suey and other substandard Cantonese fare. My only defense against bad Chinese food was to cook at home. Unable to find a good Chinese cookbook, I resorted to writing home to my aunts and other relatives for instructions and recipes.

Over the years I mastered techniques and developed recipes that helped me in my kitchen. I found that by taking one technique and switching up the ingredients, I could make an entirely new dish typical of a different region. Once I had the many methods under my belt, I could make almost anything. I hope this book will help illuminate fundamental Chinese cooking methods for the Western cook and make this fascinating cuisine practical to prepare at home.

Thus, the chapters here are organized according to cooking methods rather than the usual division by ingredients or region. Some techniques are defined by heat sources. Cooking with oil, for example, is divided into five techniques: light frying, deep-frying, oil steeping, yin-yang frying, and pan-frying. The procedures are different but all use oil as the heat medium. This approach can greatly facilitate the learning of a cuisine by identifying similarities and differences among related techniques.

Although the preparation methods outlined in this book are based on a comprehensive set of Chinese cooking techniques, I have kept the home cook in mind and have thus omitted some seldom-used ones. Many of these omitted techniques simply put too fine a point on a general method. For example, pan-frying in Chinese can be minutely defined in three ways: jian (), tie (), and ta (), depending on whether the ingredient is fried whole, cut into pieces, or covered in batter. Since the technique is fundamentally the same, I combine them into pan-frying.

SHARING A MEAL

Sharing a meal is still considered the ultimate sign of pride and respect in Chinese families. Special celebrations, such as major birthdays and weddings, are elaborate and can consist of ten to twelve courses accompanied by the best rice wine and the most expensive tea. Truly extravagant banquets are regularly hosted by the upper echelon of Chinese government officials and industry tycoons.

The main components of a Chinese meal are set by a long-standing tradition. The Chinese term for aliment, or food, is yinshi (), which literally translates as drink and food. The yin () refers to all sorts of drinks including tea, wine, and brewed herbs, whereas the shi () consists of fan () and shan (). Fan represents a group of foods made from grain, and shan comprises all the wonderful dishes made from meat and vegetables. A Chinese meal is almost always made up of these three components of yinshi . This sense of balance continues into our modern era and is reflected in both daily family meals and gala banquets.