BOOKS BY EILEEN YIN-FEI LO

The Dim Sum Book

The Chinese Banquet Cookbook

Chinas Food, coauthor

Eileen Yin-Fei Los New Cantonese Cooking

From the Earth

The Dim Sum Dumpling Book

The Chinese Way

The Chinese Kitchen

The Chinese Chicken Cookbook

My Grandmothers Chinese Kitchen

In all the world there are only two really great cuisines: the Chinese and the French. Chinas was created first, untold centuries ago, and is judged to be the greaterwhen executed by superb chefs. It is the most complicated cuisine; it uses ingredients no other employs; and it is distinctive in that, for the most part, it is cuisine la minute.

James Beard, 1973

DEDICATIONS

This book is dedicated, as have been all of my books, to my husband, Fred, my careful reader and critic of first, and last, resort, and my love. It is for my children as well, Christopher the Chef, he of the fine palate; Elena the Producer, whose careful list of eating strictures is put on hold when she enters my house; Stephen the Coach, a walking appetite, who adores eating the cooking of others; and my daughter-in-law, Cristina, the Voracious Taster. To them, I add my granddaughter, Elliott Antonia, my Siu Siu, who sat on my kitchen table and stirred and mixed with me as I wrote. Finally, I give my thanks, my deepest thanks, to Carla Glasser, my agent for many years, who cares about my work.

Contents

THE CHINESE MARKET

M y teaching, my cooking lessons always begin in the Chinese market. Heaps of vegetables, familiar and exotic; the pork butchers; the herbalists and their shops comprise my classroom, my laboratory. In them I find recurring veins of discovery. In them I teach and simultaneously I learn. Sometimes when I am at home in my kitchen, my mind focused on the foods I am preparing, my thoughts will suddenly shift to a particular shop, along a particular street, in my Chinatown. I know that the next time I visit that shop I will find the greenest, smallest, most crisp bok choy, the liveliest striped bass swimming in tanks, and mounds of freshly picked lily bulbs and garlic flown in from China.

M y teaching, my cooking lessons always begin in the Chinese market. Heaps of vegetables, familiar and exotic; the pork butchers; the herbalists and their shops comprise my classroom, my laboratory. In them I find recurring veins of discovery. In them I teach and simultaneously I learn. Sometimes when I am at home in my kitchen, my mind focused on the foods I am preparing, my thoughts will suddenly shift to a particular shop, along a particular street, in my Chinatown. I know that the next time I visit that shop I will find the greenest, smallest, most crisp bok choy, the liveliest striped bass swimming in tanks, and mounds of freshly picked lily bulbs and garlic flown in from China.

My mind is ever filled with the memories of a lifetime of cooking, learned and tested, gifts to me from the cooks and chefs, the dim sum artists and the da shi fu (kitchen masters), the farmers and fishermen in the many parts of China in which I have lived and cooked. They have given me the permanent legacy of a love and respect for food, its cultivation, and its preparation. It has been my lifes work to try to transmit to my students the appreciation I have for the traditions of my native foods.

All of this begins in the market, and my markets are many. Few markets in the world can match the freshness, breadth, and variety of those found in China, and few markets in China can compare to the Qing Ping market in Guangzhou. This unstructured retail space, which snakes its way through a zigzag of tiny alleys, began as an underground free market decades ago when vegetable and fruit growers, fishermen and poultrymen, and the driers and blenders of spices and herbs rebelled against the rigid communes of the Mao Zedong era, which they believed cared more for numbers than for freshness and quality. I have shopped in the Qing Ping market often, and on any morning I have found live chickens and ducks and their eggs; whole pigs, live and roasted; fish swimming in shallow zinc pools; crawling crabs and piles of fresh mussels and clams; and small mountains of vegetables, the dirt of the fields still clinging to their roots. Preserved and pickled foods fill ceramic barrels. Crude wooden stands and sheds, quickly nailed together, offer fresh herbs that are weighed on tiny bronze scales. This market is a visual and aromatic joy.

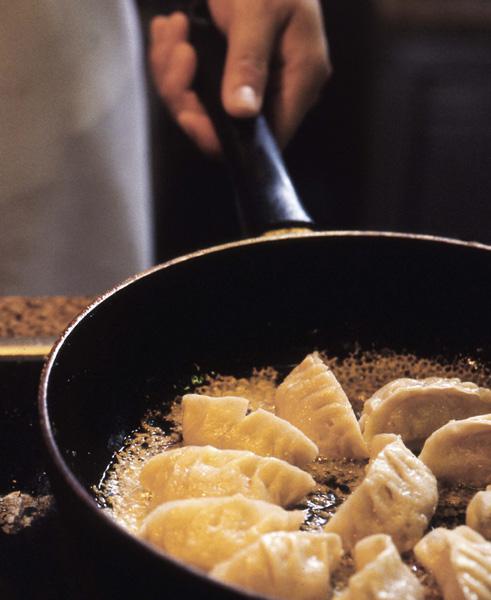

Similar markets, less imposing but equally dedicated to the freshness and quality so in demand by the Chinese, are to be found in Beijing. Most of them are movable markets, such as those along streets like Donghuamen and Bai Wan Zhuang and along the edges of Temple of Heaven Park, each determined by the unceasing urban expansion of the Chinese capital. But people will not be denied their morning dumplings, no matter where they have to go for them. Similarly, the unabated growth of Shanghai has seen the repeated upheaval of neighborhood markets, though, again, morning and afternoon shoppers remain undeterred. In Chengdu, Sichuans capital, the markets are home to the rice-flour dumplings beloved by the locals, and to the special dried reddish peppercorns that are indispensable to the cooking of western China. Fuzhou markets are a treasure trove of the fine teas and imaginative sweets of Fujian Province, in southeastern China. Regional variety, provincial smells, the foods of traditionthese are the many markets of China.

In Hong Kong, just south of Guangzhou, the rivals to Qing Ping are Sham Shui Po, a sprawling enclave on the route north out of Kowloon toward the New Territories, which border on China proper, and Yau Ma Tei in central Kowloon. I regard them highly, and they are my neighborhood markets when I am in Hong Kong. Sham Shui Po spreads its web among avenues, streets, and tiny dead-end alleys, offering live chickens, ducks, and squabs. Its fish swim in tanks, where they wait to be chosen by housewife or amah, netted, and once approved, bopped on the head with a wooden mallet, scaled, slit, gutted, and then packed into a plastic sack of sea or river water for the trip home. Yau Ma Tei is a vast, open market, a collection of working pork butchers, chicken pluckers, and fishmongers, with knife sharpeners honing cleavers on rotating stones, next to vegetable and fruit stands and herb growers and driers. On my periodic trips to Hong Kong, I never fail to visit these markets, if only to look at and inhale the sights and smells I remember from my childhood in the markets of Sun Tak Yuen, the district near Guangzhou of my birth.

Because Hong Kongs residents are intensely preoccupied with food and eating, all manner of different markets thrive in this former British colony, now a special administrative region of the Peoples Republic of China. In Wanchai, near the Royal Hong Kong Yacht Club, a market catering to what was once a lively neighborhood of boat people exists in the remnants of the Causeway Bay Typhoon Shelter. West of Hong Kong Islands Central District lies the Western District, possibly the worlds largest collection of shops selling dried herbs and spices imported from all over Asia. Here, too, are hundreds of dealers who trade in the dried exotica of Chinas cuisine: sharks fins; very special, very dear abalone from Japan; sea cucumbers; and birds nests, the saliva-woven homes of Southeast Asian swifts, destined for soups believed to heighten female beauty and prolong youth.

Next page

M y teaching, my cooking lessons always begin in the Chinese market. Heaps of vegetables, familiar and exotic; the pork butchers; the herbalists and their shops comprise my classroom, my laboratory. In them I find recurring veins of discovery. In them I teach and simultaneously I learn. Sometimes when I am at home in my kitchen, my mind focused on the foods I am preparing, my thoughts will suddenly shift to a particular shop, along a particular street, in my Chinatown. I know that the next time I visit that shop I will find the greenest, smallest, most crisp bok choy, the liveliest striped bass swimming in tanks, and mounds of freshly picked lily bulbs and garlic flown in from China.

M y teaching, my cooking lessons always begin in the Chinese market. Heaps of vegetables, familiar and exotic; the pork butchers; the herbalists and their shops comprise my classroom, my laboratory. In them I find recurring veins of discovery. In them I teach and simultaneously I learn. Sometimes when I am at home in my kitchen, my mind focused on the foods I am preparing, my thoughts will suddenly shift to a particular shop, along a particular street, in my Chinatown. I know that the next time I visit that shop I will find the greenest, smallest, most crisp bok choy, the liveliest striped bass swimming in tanks, and mounds of freshly picked lily bulbs and garlic flown in from China.