5. Rich Breads

For better or worse (and probably to your great relief), I am not going to rehash the extensive history of bread. Its a fine story and one worth reading, but authors like H. E. Jacobs have done that well (see the Resources section). Besides, Ive already given a synopsis of the six-thousand-year history in both Crust and Crumb and Peter Reinharts Whole Grain Breads. I believe what readers of this book really want to learn is how to make world-class breads quickly and easily. To accomplish this, we need only look at the discoveries and breakthroughs of recent years.

So heres a quick recap: The three waves that led to improved bread in the United States can be identified as the whole grain wave, the traditional wave, and the neo-traditional wave. The whole grain movement of the late 1960s was part of the counterculture era, in which white flour (and white sugar) symbolized industrialization and mainstream thinking, while whole grains became the symbol of a healthful, holistic way of life that had fallen by the wayside. During this period, organic foods were first promoted as an alternative to highly processed foods grown with chemical fertilizers and pesticides, ushering in what we now call the green movement. This whole grain wave introduced my generation to an alternative way of relating to food, but it took a few more years for dietary habits to change dramatically. Part of the problem was that most of the whole grain breads of that era, while nutritionally superior, werent particularly delicious (or even palatable), so they came to be labeled health food breads, not fit for general consumption.

The 1970s and 1980s saw the emergence of the traditional wave, characterized by a culinary renaissance in which European chefs and bakers came to our shores. Likewise many Americans who exerted considerable culinary influence traveled abroad to experience the great food traditions of other cultures.

The third movement, the neo-traditional wave, grew from the second movement as regional cuisine in the United States became the local and domestic expression of traditional European and Asian influences. Bakeries applied classic techniques to create distinctly American breads and pastries. At my bakery, Brother Junipers, we applied slow fermentation processes to create breads using ingredients that would match well with the foods of the Sonoma County wine region or pay tribute to various other regional cuisines.

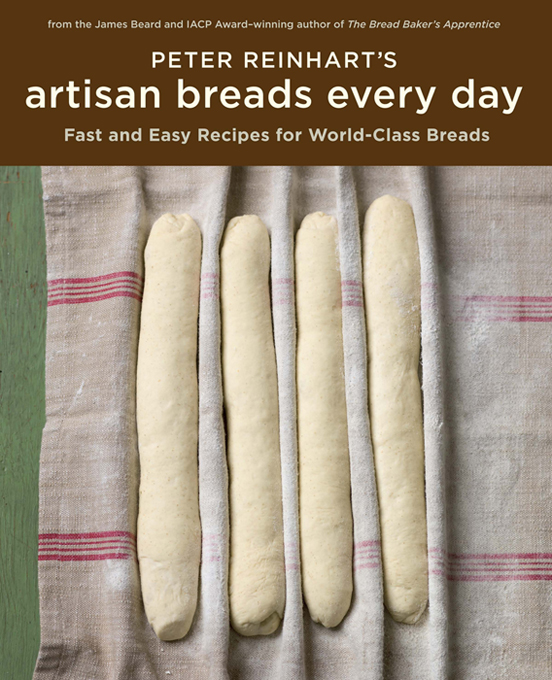

These three waves converged in the 1990s to create what is now known as the artisan bread movement. Meanwhile, many bread experts published books that shared their emerging and ever-evolving knowledge with home bakers, who were also growing in number. Bread machines helped fuel this trend, taking some of the intimidation out of the process. But more valuable, I think, was that Americans had finally experienced higher-quality breads, via restaurants and local bakeries, and they wanted to be able to replicate these breads at home. (This was also true of citizens around the world who were rediscovering their own countrys bread heritage.) Every new book seemed to add yet another missing piece of the puzzle, and Internet discussion groups became abuzz with home bakers sharing their victory stories or asking for advice. Slow rise and slow food became a metaphor for better breadand a better, more satisfying life in general. This era saw the inception of the Bread Bakers Guild of America and the international Slow Food movement, followed soon thereafter by the establishment of the Whole Grains Council and many other organizations promoting healthier, tastier, safer foods. The concept of a green lifestyle and cuisine finally spilled over into mainstream thinking, and, ironically, the best-selling bread book of recent times promised (and delivered!) artisan-quality breads faster rather than slower. The circle had closed.

Recently, I was asked to speak at a professional bakers convention on the subject of making artisan bread quickly and easily. My first reaction was that this seemed like an oxymoron. Artisanal methods arent supposed to be easy; otherwise, everyone would already be using them. But upon reflection, I realized that this is already happening in the industry due to modern technological breakthroughs. Refrigeration didnt exist a hundred years ago, when bakers relied upon pre-ferments to extend fermentation time. Twenty years ago, we didnt have sensitive manufacturing equipment that could handle wet, sticky dough without damaging it. Only recently have American bakers grasped the biological and chemical processes of transformation that occur during bread making, the journey from wheat to eat, though there are certainly always new mysteries waiting to be unraveled. So perhaps it isnt an oxymoron at all, and given the new methods developed by other bakers and authors, and the public interest in new, streamlined methods, the time seems right for a fresh synthesis of all of the techniques that arose in the quest for the perfect loaf and loaves.

The past few years have seen the publication of a number of bread books that offer original methods for simplifying the bread making process. Yet during the same period, a few excellent books have appeared that reveal the advanced methods of true artisan bakers from around the world. We want it all: great bread, but fast and easy. Yes, it does seem like a contradiction since the premise of artisan bread is long, slow fermentation. Despite the often complex descriptions of methodology, bread making actually isnt all that difficult, so achieving the easy part is, well, easy. The fast part is where the challenge comes in.

Baking is primarily about the balancing act between time, temperature, and ingredients. Everything else is connected to this. In my previous books, I have taken readers on a journey in search of all of the workable variations on this theme of time, temperature, and ingredients. My goal in this book is to further synthesize that knowledge and apply it in a new way to create a system of baking that anyone can understand and perform.

![Ken Forkish - Evolutions in Bread: Artisan Pan Breads and Dutch-Oven Loaves at Home [A baking book]](/uploads/posts/book/323066/thumbs/ken-forkish-evolutions-in-bread-artisan-pan.jpg)