Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

Acknowledgments

I have to pay tribute to the irreplaceable work of Kat Merck, who has done first line editing and recipe testing for all three of my books. The steady email dialog that we had, morning and night, was fun in itself, and for this book her work was essential. Kat tested every recipe in this book and fed her family a lot of bread. Her input and her sharing of successes and not-so-much-successes helped me refine the recipes to work for you.

I am proud to be an author for Ten Speed Press. A big shout-out to Kelly Snowden, who was the editor for this book, and the supporting cast who made it look like I can pass an English composition class. Also, a special tip of the hat to Betsy Stromberg, who did the design and layout of this beautiful book.

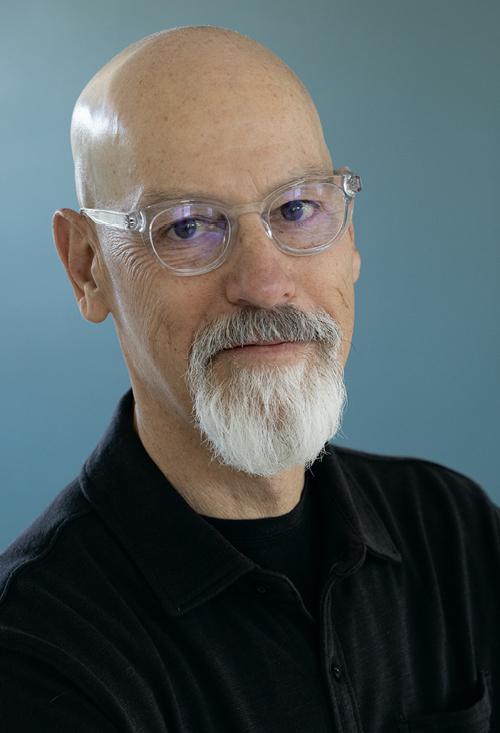

Finally, Alan Weiner has photographed all three of my books. Alan worked as a photojournalist for the New York Times for over twenty years, and I knew from the beginning that his eye for the interesting detail would suit my photographic taste in cookbook production. When I got my first copy of this book, with photos placed throughout, I was thrilled, and when I flip through it, I admire the photography every time.

About the Contributors

Ken Forkish is the founder of Kens Artisan Bakery, Kens Artisan Pizza, and Checkerboard Pizza, all in Portland, Oregon. He is also the author of James Beard Award and IACP Awardwinning book Flour Water Salt Yeast and a 2016 ode to pizza, The Elements of Pizza .

Ken was a key contributor to Portlands culinary evolution, founding Kens Artisan Bakery in 2001 and Kens Artisan Pizza in 2006. He was a finalist for the national James Beard Award for Outstanding Pastry Chef in 2013 and Outstanding Baker in 2017. In 2013, Ken opened Trifecta Tavern & Bakery, an award-winning bar, restaurant, and small-batch bakery that closed at its peak in late 2019. Kens Artisan Bakery was sold to two long-standing employees, and Kens Artisan Pizza was sold to a longtime friend.

His expert recipe tester for the book was Junior (pictured below).

Alan Weiner fell hopelessly in love with photography when he was ten years old. After earning a degree in journalism, he worked for the New York Times , traveling the world for twenty years. Since then, he has worked as a food, portrait, and corporate photographer. He is based in Portland, Oregon.

Junior

Chapter 1

Ingredients & Equipment

Baking excellent bread at home is easy, once youve done it a few times, if you have good instructions, a few pieces of versatile kitchen gear, and, as always, good-quality ingredients. Readers of my first book should review this section as there is plenty of new information on flour and where to buy it as well as bread pans to work with the recipes.

Ingredients

What kind of flour should you buy to make good bread at home? There are more choices than ever before if you are willing to buy online and seek out flour mills in your region. High-quality stone-milled flour is an option alongside the workhorse white flour that you can obtain at the store. Even the flour that I buy for my bakery is superior to what was available twenty years ago. Well-known bakers are promoting wheat farmers and craft mills like never before, and greater public demand is creating new markets for excellent flours and grains that you can bake with at home.

Some of the stories of interesting wheat varieties follow in this chapter, and there is more detail about heritage-grain flours in the recipe headnotes. I like white bread, too, and white bread flour has a strong supporting role in most of my craft-flour bread recipes, as I blend flours together to get a good rise and texture.

Flour, ancient grains, and additional varieties of wheat get the lions share of this section, but lets first review the other ingredients: water, salt, and yeast. They all matter.

Water

Tap water is normally fine. Filtered tap water is probably better, depending on your source. If your water is good enough to drink, its good enough for baking.

Salt

When baking, I prefer fine sea salt. Avoid iodized salt because iodine inhibits fermentation and you can taste it. Since the grain size of salt varies from source to source, volume measurements tend to be inconsistent. Therefore, its far better to weigh your salt. I recommend using fine sea salt because it will dissolve quickly in the dough.

Salt slows the fermentation of bread dough, and thats a good thing. Without it, bread dough will rise very fast and taste insipid. Salt also somewhat inhibits water absorption by the flour, so it is often added at a second mix stage. The standard amount of salt in bread recipes is 2 percent of the weight of the flour. The generally accepted range is between 1.8 and 2.2 percent.

Yeast

All the recipes in this book except the Dutch-oven levain breads call for instant dried yeast. Youre likely to find two or three kinds of yeast at the store: active dry, rapid rise, and instant. All these yeasts are the same species: Saccharomyces cerevisiae . What differentiates them is their coating, the way the yeast is manufactured, and performance. The rise times may vary a little bit from brand to brand, so pay attention to the recipe guidelines for volume expansion in the dough to tell you when to go on to the next step. At my bakery, we use Saf-Instant Red Yeast. I recommend that you buy a 16-ounce package of this yeast, which is available online. It will keep for a year if stored airtight in the refrigerator.

In my recipes, it isnt necessary to dissolve the dried yeast first. These doughs have a lot of water in them, so the yeast dissolves rapidly in the dough. Just sprinkle it on top and incorporate as you mix with a wet hand.

Professional bakers use the term commercial yeast to refer to what consumers think of as store-bought yeast. Commercial yeast is a monoculture, a single species of yeast (the aforementioned S. cerevisiae ). Levain cultures, in contrast, are made up of a community of yeasts that occur naturally in the flour and the environment, including the air. These wild yeasts arent like commercial yeast; they are less vigorous and they impart their own particular flavors to the bread. Part of the complexity of flavors in a levain bread is due to multiple strains of yeast coexisting within the culture that is leavening the dough.

Commercial yeast causes bread dough to rise faster and provides more lift, producing bread with a lighter texture and more volume than levain breads. The slower yeast activity in levain dough allows time for naturally occurring lactic acid bacteria to undergo their own fermentation and impart acidity, which gives the bread more complex flavor, a bit of tang, and a heartier crust. And because of this acidity, levain breads keep longer before going stale.

![Ken Forkish Evolutions in Bread: Artisan Pan Breads and Dutch-Oven Loaves at Home [A baking book]](/uploads/posts/book/323066/thumbs/ken-forkish-evolutions-in-bread-artisan-pan.jpg)