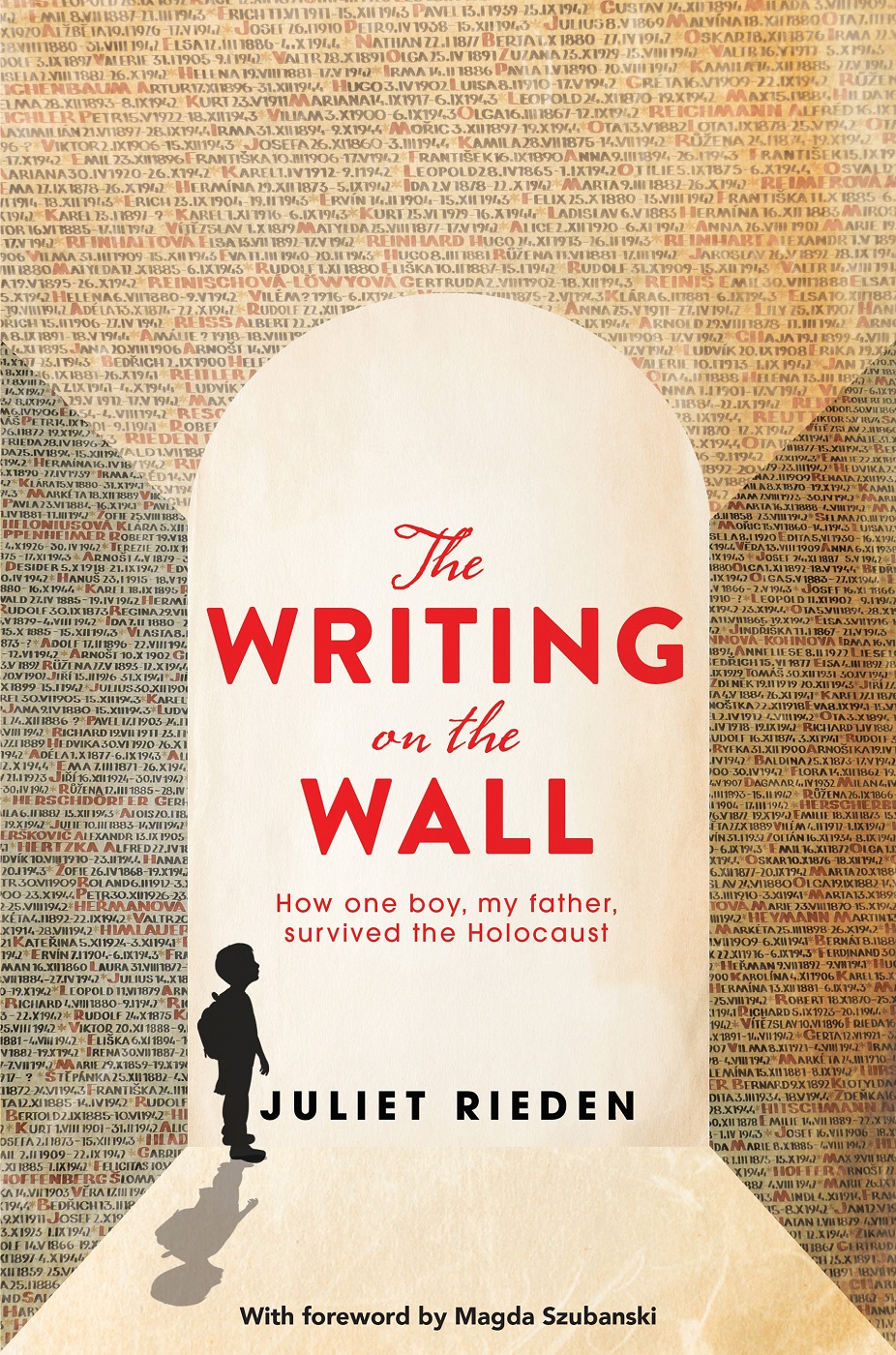

About The Writing on the Wall

Memoirs such as this will ensure we do not lose the struggle against forgetting that sly accomplice of tyranny. Magda Szubanski

In 1939, as Hitlers troops march on Prague, a Jewish couple makes a heartbreaking decision that will save their eight-year-old sons life but change their family forever.

Australian journalist Juliet Rieden grew up in England in the 1960s and 70s always sensing that her family was different in some way. She longed to have relatives and knew precious little about her Czech fathers childhood as a refugee.

On the night before Juliets father died, in 2006, Juliets father suddenly looked up and said: The plane is in the hangar. In the years after his death, Juliet comes to truly understand the significance of these words.

On a trip to Prague she is shocked to see the Rieden name written many times over on the walls of the Pinkas Synagogue memorial. These names become the catalyst for a life-changing journey that uncovers a personal Holocaust tragedy of epic proportions.

Juliet traces the grim fate of her fathers cousins, aunts and uncles on visits to Auschwitz and Theresienstadt concentration camps and learns about the extremes of cruelty, courage and kindness.

Then in a locked box in Britains National Archives, she discovers a stash of documents including letters from her father that reveal intimate details of his struggle.

Meticulously researched and beautifully told, this is the moving story of a womans quest to piece together the hidden parts of her fathers life and the unimaginable losses he was determined to protect his children from.

This book is dedicated to my fathers aunts and uncles and their children and especially Ida Hoffer. You are the family I never knew I had, but longed to embrace. To my grandparents Rudolf and Helena whose sacrifice is the reason I am here writing this book and to my father, Hanus, whose quiet dignity in the face of deep trauma and unconditional love for us, his family, takes my breath away.

Contents

Foreword

The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.

Milan Kundera, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting

I first met Juliet Rieden when she interviewed me for The Australian Womens Weekly in 2012 after I came out live on television in support of Marriage Equality. I was still very nervous and felt extremely vulnerable. Juliet relayed my story with compassion, fairness and dignity.

Since then we have crossed paths a few times, and when I launched my own memoir Juliet again interviewed me. She mentioned at the time how strongly my familys experiences resonated with her. I suggested that she take the journey to find the truth of her own story.

And this is that story.

Little did I realise just how much her life and history parallels that of my own and many other refugee families. Like me, she is the English-born descendent of urbane Eastern Europeans who were plunged into hell. Like my father, her father identified as an Englishman. And, like me, she is haunted by questions of what happened to her family.

But there are poignant differences. My family tried to save their Jewish friends and neighbours from the flames of the Holocaust. Many in Juliets family did not survive. This deeply moving account reminds us that even those who did not perish in the flames were severely burned by their cruel heat.

This brave, intelligent book is also a penetrating investigation into acts of charity. Saving people does not always come from pure altruism and can have complex, mixed motives. Juliets father John (or actually Hanus) was part of something similar to the famous Kindertransports, only her father travelled to England by plane not train. She uses her journalistic detective skills and storytelling ability to bring to life the terrible loneliness and exile that was the cost of his survival.

Families usually keep secrets for one, or perhaps both, of two reasons pain and shame. Unbearable pain. Unbearable shame. It takes great courage and compassion to prise open that locked door of the heart. To set about answering those awful questions: what happened to my family and, maybe even harder, what did they do to survive? What did they do in impossible circumstances?

Understandably, much of the telling of the Holocaust has been about Auschwitz. But it was not the only hell on earth. Juliet also takes us into the bizarre world of Theresienstadt, the model show camp that provided a mask for the horror of the Final Solution.

Walking in the footsteps of her extended family, many of whom did not survive, Juliet paints vivid, heartbreaking pictures. She provides names, dates and places.

As the last generation of Jewish survivors of the Holocaust pass from this earth, their stories will not disappear with them. They will not fade into oblivion, unremembered. Through Juliets diligence and love, they exist once more, proof that not even Hitler can erase my family without a trace.

Memoirs such as this will ensure we do not lose the struggle against forgetting that sly accomplice of tyranny.

Magda Szubanski

Prologue

Lifting the curtain

As I stare at the wall of Pragues Pinkas Synagogue, I feel a blaze of heat flush through my body and my heart begins to pound and stutter. The etched letters are dancing in front of my eyes, the red now taking on the ghoulish taint of dried blood. My knees buckle and I grasp the railing in front of me, gripping it white-knuckle tight, eager not to make a scene. An uncomfortable tingling is running up and down my spine, tapping through each vertebra. Is someone there looking over my shoulder? I check behind me but no one is interested in me; all are transfixed by the wall, lost in their own torment. Retreating, I turn away and bend secretively over my phone for a frantic internet search.

And then everything changes.

It makes me sad and a little angry that I discovered the family I never knew from Google. I think I held my breath as I jabbed in the names I had just discovered on the wall Emil Rieden, Berta Rieden, Felix Rieden, Ota Rieden and then added Holocaust to my internet search. Could these really be my people on the wall of this memorial to Czechs murdered by the Nazis?

The answers came at one click. It was that easy.

Emil was my great-grandfather, Berta and Felix my great-aunt and great-uncle, and Ota... well, Ota (an innocent spelling error from the calligrapher who painted the names) should have read Otto, who was their brother, another great-uncle. All three were siblings of my grandpa Dr Rudolf Rieden; Emil was his father. And all, I later discovered, lived with my dad, Hanus Rieden, before he fled to England from Czechoslovakia in March 1939, only a week before Hitlers troops arrived in Prague, part of an elaborate and desperate escape when he was aged just eight. He never saw them again.

It was the first day of September in 2016 and I was 52 years old. How could I have been ignorant to their fate all this time? Why didnt my father tell me?

I turn back to the writing on the wall, now feeling ownership, but still incredulous. Next to each name, dates of birth and death are carefully painted. And as I push my brain to work out their ages, tears start to roll down my face.

I always knew our family was different.

For a start, while we lived in the heart of commuter-belt Surrey, on Londons outskirts, both our parents were only children and our grandparents lived in other countries Mums parents 17,000 kilometres away, on the other side of the world in Australia; Dads trapped behind the Iron Curtain in Eastern Bloc Czechoslovakia. Our Australian grandparents, Flo and Roy, came over every few years in a big flourish with exotic gifts for my two brothers and me, and tales of stopping off at places like Singapore and Ceylon.